|

|

|

|

The CSA Propylaea Project has taken on more complex aims and a more definite form, thanks to recent meetings in Athens among the principle participants, Propylaea architect Tasos Tanoulas, Propylaea structural engineer Mary Ioannidou, and CSA Director, Harrison Eiteljorg, II. The initial aim had been the creation of a CAD model of the structure, based upon the drawings already made by the Propylaea team, but a thorough examination of the possibilities made it clear that a more ambitious project is required.

We began with the most obvious problem: how should the blocks of the Propylaea - including the broken and battered ones - be modeled? Answering that question led us inexorably toward a broader definition of the project.

There are two ways to make good three-dimensional CAD models. The stones can be modeled as solid objects or they can be modeled as a group of surfaces only. The former is preferable in the sense that the model is more complete if all objects are understood in their full complexity. It is also easier to model a moderately complex block as a solid than as a collection of surfaces, and there are many kinds of engineering analyses that can be performed with solid models but not with surface models. On the other hand, one cannot make a solid model of a block that remains immured in a wall. Only the visible surfaces can be measured or otherwise examined, leaving much of the block unknown. A solid model of such a block would depend on unproven assumptions about the invisible portions of the block. Therefore, modeling all parts of the Propylaea as solids is not possible; many of the blocks are still in the building and have only one or two faces visible.

Fig. 1 - Blocks drawn partly as solids and partly as surfaces. Note that there is no apparent difference when the blocks are part

Fig. 1 - Blocks drawn partly as solids and partly as surfaces. Note that there is no apparent difference when the blocks are part

The blocks that have been removed from the building, of course, can be fully modeled, complete with cuttings for clamps and dowels and similar details. As a result, the building could either be modeled entirely as a series of surfaces or partly as surfaces and partly as solids. It could not be modeled entirely as a collection of solids, though, because it is impossible to obtain the information required to do that.

Fig. 2 - A block from the Propylaea modeled as a solid and shown in a three-point perspective view.

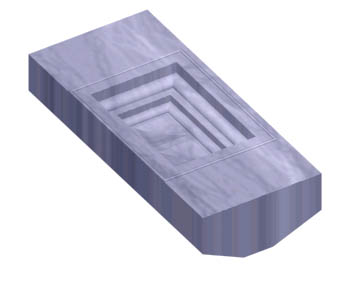

Fig. 3 - A ceiling coffer from the Propylaea modeled as a solid and rendered

with a primitive marble texture map (but in an isometric rather than

a perspective view).

While we discussed the question of solids versus surface models, we also had to face the difficulty of actually making either kind of model when our subject matter consists of many battered and broken stones. CAD programs are very good at making regular shapes, but making irregular shapes is not only difficult, it is very time-consuming. Using complex three-dimensional scanners would make it possible to generate surface models of the blocks with less difficulty, in the same way that some sculpture is now being modeled, but only after spending a great deal of money on a scanner capable of dealing with these blocks. In addition, each block would need to be scanned, and a good deal of time would be required. (Paper drawings, of course, cannot really show the broken stones with full accuracy either, because the drawings are. at best, two-dimensional abstractions. Regular blocks can be fully defined and described in drawings, but irregular ones cannot.)

Fig. 4 - The central portion of the Propylaea with two column drums

no longer in situ. Note the shapes of those drums, particularly the

drum on the left; they would be all but impossible to model accurately.

As we debated the possibilities for modeling, we also discussed what should to be included in the model for it to be useful. Should the model include a fully accurate version of each stone, complete with broken edges and battered faces? If so, why? If so, how?

We all agreed that the information about the current conditions of the building stones is valuable and should be kept, but we also agreed that individual blocks did not need to be modeled in the CAD system with the broken surfaces. Instead, we concluded that models of stones in their original, unbroken shapes should be made whenever possible, and that the existing drawings of those stones should be scanned and included in the CAD model as well. (We did not decide what to do about a battered stone whose original shape cannot be determined; when a specific example occurs, we will decide how best to deal with it.)The result will be a single CAD model with a combination of idealized parts and scanned drawings - a solution that preserves the information and provides it in a useful fashion without adding unnecessary complexity to the task. All documentation is preserved and made available in a single resource, and a CAD model of the entire building is a part of that resource. We will closely integrate the scanned drawings and the relevant blocks in the CAD model so that a user can readily see the original shape and the current state of any block simultaneously. (In the future, it may be possible to put the equivalent of an existing paper drawing directly into the CAD system and to by-pass the making of paper drawings of individual blocks, but that is something that will not be considered for some time.)

We agreed in addition to mix solids and surfaces in the model. Users of the model will not see a difference, and dimensional information will be unaffected. However, scholars will have better representations of some parts of the structure, better especially if they want to do any structural analyses, than if we used surface models only.

Once the decisions had been made to include scanned drawings in the CAD model, it seemed that it would also make sense to include scanned versions of the photographs in the Propylaea files. That, in turn, led us to add text items that would allow the total set of digital materials to be as complete as possible and, as a result, a scholarly resource of greater value and significance than our original plan of a CAD model.

When the scope of the project had been settled, it seemed apparent that a Web site should be set up to disseminate information about the project and to serve as the access point for those seeking the CAD model, drawings, images, or other resources. The domain name has been reserved, and there will soon be a Web site located at propylaea.org. Initially, the site will contain only information about the project and project procedures, but it will eventually provide access to all the data available. Some of those data will be online and available for immediate downloading or viewing, but the volume of material is too great for all of it to be kept online. Therefore, we expect that much of the information will be available only on request.

The value of this project is two-fold. It will be a crucial resource for scholars who are interested in the Propylaea or other buildings of the Classical period. The project will also be a model for the complete digitization of an important architectural landmark, and project personnel will strongly emphasize the processes used, problems encountered, and solutions tested in various publications as well as on the Web site. In the end, we hope not only to provide information about this building but also to provide guidance for any scholar who wants to follow a similar path with another building. To that end, we have also planned two one-year fellowships for graduate students who will learn to use AutoCAD and then work on the project in Athens.

For other Newsletter articles concerning applications of CAD modeling in archaeology and architectural history; Electronic Publishing; the Propylaea Project and other CSA Projects; or the use of electronic media in the humanities; consult the Subject index.

Next Article: Archiving Data Serves Multiple Purposes

Table of Contents for the Spring, 2000 issue of the CSA Newsletter (Vol. XII, no. 3)

Table of Contents for all CSA Newsletter issues on the Web

Table of Contents for all CSA Newsletter issues on the Web