|

Sarah Whitcher Kansa and Eric C. Kansa

(See email contacts page for the author's email address.)

The Alexandria Archive Institute and the School of Information at UC Berkeley recently launched a study exploring how open technologies can best meet the needs of the diverse communities of scholars working with cultural-heritage content. This 2-year endeavor is funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), as part of their Advancing Knowledge: The IMLS/NEH Digital Partnership grant program. This paper presents some of our initial findings of user experience in archaeology, an under-studied and essential foundation for the successful development and deployment of computing systems to enhance humanities research.

Many systems for sharing archaeological content have come on line in recent years. These systems have made tremendous strides in developing ways to share content that would otherwise be difficult to access or use. However, most are tailored to meet specific needs on a project-specific level. This is true for most archaeological project that share data—in general, they tend to be custom-built systems that require specific knowledge of the project to explore in any depth. On the other end of the spectrum are popular, but not archaeology-specific systems such as Flickr, the popular photo sharing site, which are sufficiently generalized to meet most needs, but on a very superficial level.

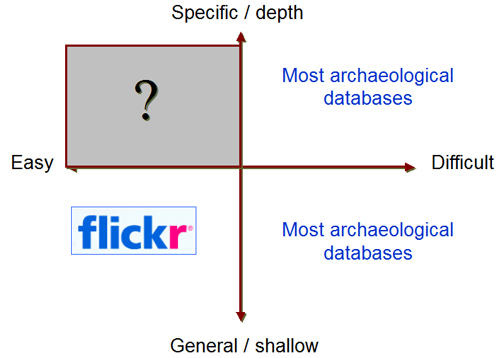

Fig. 1. Ease of Use and Depth of Content as Site Variables.

In the case of archaeology, this experimentation in content sharing is ongoing, and at the moment, there appears to be a split between systems that provide customized, deep exploration and those that offer easy-to-use, casual browsing. We can attempt to visualize this by laying out a spectrum on two axes (see figure 1). Of course, there are other axes we could add to this diagram, such as the reliability, cost, and degree of openness. For now, we'll explore these two, where the x-axis represents ease of use and y-axis represents depth of content.

Resources such as Flickr fall into the "easy but shallow" category. Certainly, there is some depth to be found, but achieving the desired depth requires lots of clicking around and altering your search strings, thus increasing the difficulty. This is because Flickr does not offer great precision in its search features; nor are there reliable categories for data items. Archaeological data sharing sites tend to fall into the area of "difficult to use," and they offer a range of superficial and in-depth content. This is because they are often tailor-made for a specific project, at a pretty high cost, and thus they contain only project-related content. While these systems may be very useful for a specific subset of researchers, the content in these systems is more or less stuck in a silo. That is, it is hard to get content out of these systems in formats useful for analysis or aggregation.

We cannot imagine that users are satisfied with these two extreme options in data access. Might it be possible to find a middle ground that allows for both in-depth research and easy, fast retrieval of archaeological content, thus meeting the needs of diverse user communities? We would hope the answer is "yes," but first we have to try to figure out just what those needs are.

Our exploration of user needs begins by looking at the impact and use of current systems. Simply building a service doesn't necessarily mean that people will use it. What is it that makes users come to a site and find value in it? There is no one answer to this question, but a general rule of thumb is that users should find a resource appealing, credible, easy to use and relevant toward meeting specific goals. These necessities make up the "user experience," or a person's overall impression when using a product or system.

We are currently engaged in a study that addresses these questions through an in-depth exploration of archaeologists' experience and satisfaction with current web tools. Our research will help guide developments to Open Context, the open source system described in the article "Open Context: Developing Common Solutions for Data Sharing" in the last issue of the CSA Newsletter.

Briefly, Open Context offers integrated access and services across datasets pooled from multiple research projects and collections. Open Context has been in development since 2006. The first phase involved validating the data model upon which it's built. At that time, we populated it with data from ten different field and museum projects, ranging from small to extremely large, each with its own unique nomenclature, which is retained upon import to the system. The intention behind this was to get enough diversity of content to test the capabilities of the system in serving different types of content. The second phase of the project improved the system based on what we learned from working with these diverse datasets. This second phase, funded in 2008 by a National Endowment for the Humanities Digital Humanities Fellowship to Eric Kansa, the project's lead developer, focused on adding new content, enhancing the system's speed, and redesigning the system to be entirely feed-based. ("Feed-based" here means that the system converts all of its content into a format that can be "fed" from Open Context and read by other systems, thus facilitating interoperability and reuse. We are now moving into the third phase of Open Context's development, which involves exploring the needs of researchers and working through an iterative process of design and evaluation to produce tools and services that help address those needs. We hope to arrive at an answer to this question by observing real, live users of digital content working in their "natural environment," with all the associated expectations, requirements, and limitations of their practice.

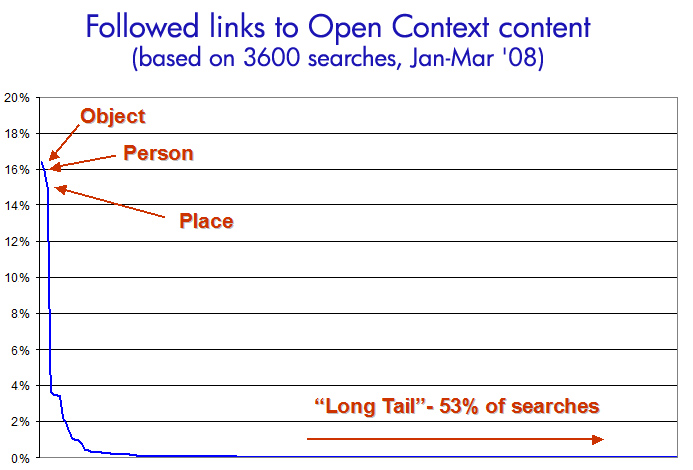

It is probably impossible to build an objectively "perfect" resource that will function well across different communities with specific needs and working in diverse contexts. For example, a 3-month study of search strings that linked to Open Context content resulted in the graph shown in figure 2. This classic "long-tail" shows that most users are looking for something that could be classified as a person, an object or a place. These three categories account for almost half of the searches. The remaining 53% of searches were for a variety of things that could not be easily grouped into categories. While it is informative to us to know that people are seeking all sorts of information, we are left wondering: What were they seeking? And did any of them find it?

Fig. 2. Search terms used to access Open Context content.

In order to try better to understand what it is that users want, we are conducting a series of interviews, surveys and focus groups with archaeologists who produce and use digital content in their work. Our discussion from this point forward will draw upon our initial analyses of the results of these exchanges. The participants come from a variety of backgrounds, spanning field archaeologists to cultural resource managers to independent specialists. It has become clear immediately in this study that all researchers have their own unique ways of working and communicating with their respective communities.

The diversity of tools that they use is staggering: some people are very interested in specific tools to share content within their community; others want a database tool to take to the field during excavation; and still others want broad project information linked to specific datasets, images and publications. Copyright, security and access concerns are pervasive, yet differ from person to person, depending on the context in which they work and their past experiences with sharing content.

What is Your Dream Tool?

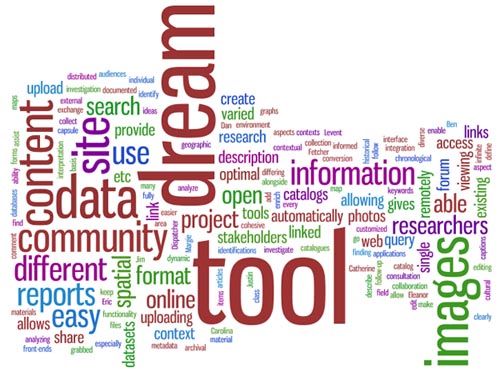

In order to find out what archaeologists want to do with primary data and how they want to interact with it, we asked our participants to define their perfect resource. Here's how we put it: Describe your digital "dream tool" for research? What would it offer? How would you use it? How would others use it? How would it change the way you do your work? The responses, as expected, were extremely diverse (figure 3); however, we were able to identify some common needs:

Fig. 3. Dream tools.

Above all, the "dream tools" described by all these people work toward two ends: comprehensiveness and efficiency. People want a tool that will allow them to ask a question and be assured that they're getting all the information from all the sources in a given region. This makes their research faster and also assures them that they are attaining sufficient depth of information.

Learning from this, we are attempting with Open Context to make it easier to customize tools and content. This will give more options for different very specialized communities to create contexts that work for their niche interests.

To this end, Open Context is currently developing an assortment of RESTful web services. REST (Representational State Transfer) is the term used for for networked information systems that provide information resources at specific addresses so that they can be retrieved by simple requests to the proper URL. The World Wide Web itself is built on this same idea of resources bound to URLs. This approach removes the need for exchanging more elaborate messages to to get information. You get the data you seek in a format convenient for reuse and processing through no more fuss and bother than just following a hyperlink. This contrasts with some of the more elaborate enterprise-style "web services" approaches taken in cyberinfrastructure, digital library, and commercial enterprise systems. These more elaborate web services often turn out to be costly to implement and maintain. Such enterprise-style web services tend to place higher barriers to entry in adoption, thus limiting community uptake and use. For these reasons, Open Context favors RESTful web services.

The use of RESTful services will aid in breaking content out of silos for easier discovery and reuse and, related to this, addressing the extreme diversity of needs of various archaeological communities and researchers by providing tools for customization. A few examples of ways that Open Context goes about this include the following:

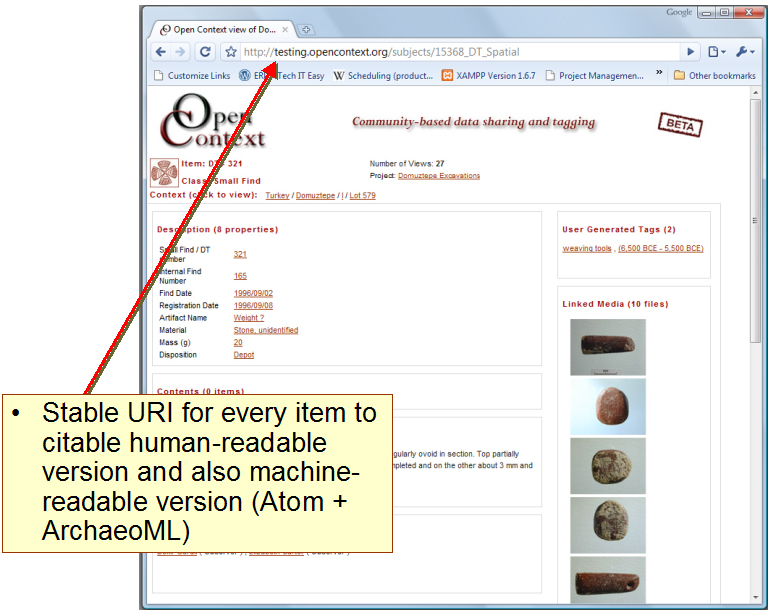

Most importantly, these data items can be transmitted by way of an Atom feed to any computer on the Internet. An Atom feed is simply a list of links that, taken together, comprise the response to an individual query. Each link is a "machine-readable" (XML) version of the data for one specific item satisfying the query condition(s). Each XML document describes the full context of its data item, including spatial context and the research and social context (such as "Who made this observation?" and "What project or collection did this observation come from?"). Because each Atom feed describes relationships in a common and well-defined way, this approach has interesting applications to archeological data sharing. A system can generate an Atom feed of items that share some sort of contextual relationship (coming from a certain place or project, associated with a certain person, etc.), just as Open Context does with its faceted browsing feature.

Fig. 4. Stable URLs in Open Context.

These tools all work towards enabling machine-readability of content. Machine-readability is important because it permits the computer to find and aggregate content from any number of web resources according to user-defined needs. Our research indicates that archaeologists, on the whole, want to be able to access quality content on a regional level, and to know that they are being exhaustive in their research. However, given the highly specialized nature of most researchers' interests, it is very difficult for one system to amass enough content to be relevant to many researchers. For example, Open Context is currently great for people interested in the Nabateans, or in the Halaf Period of the Near East, but it is of little relevance to most other archaeologists. In order to have relevant material available for most researchers, we must distribute the job of data sharing across the community. This can be achieved by implementing the types of RESTful web services described above, and we recommend that this kind of transparency and access be high on the agenda when it comes to designing digital tools for archaeological communication.

-- Sarah Whitcher Kansa and Eric C. Kansa

An index by subject for all CSA Newsletter issues may be found at csanet.org/newsletter/nlxref.html; included there are listings for articles concerning the use of electronic media in the humanities and articles concerning the ADAP and issues surrounding digital archiving.

Table of Contents for the April, 2009, issue of the CSA Newsletter (Vol. XXII, No. 1)

Table of Contents for all CSA Newsletter issues on the Web

Table of Contents for all CSA Newsletter issues on the Web

| CSA Home Page |