|

|

|

|

Web Site Review: Digital Egypt and the OEE Scenes-Detail Database

The Oxford Expedition to Egypt, Scenes-details Database

Authorship: The team of the Oxford Expedition to Egypt (OEE). No specific individuals are mentioned. The email announcement of the site stated that the database was created by created by Yvonne Harpur, Paolo Scremin, Khaled Abdallah Daoud and Andrew Leighton-Sims and that the work was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC).

Site host: Archaeology Data Service (ADS), University of York, York, UK.

Peer review, permanence: There is no mention of peer review or long term availability on the site.1

Site maintenance: There is no mention of site maintenance. There is the usual disclaimer on the home page that refers all inquiries to "the depositor," in this case the OEE.

Digital Egypt for Universities

Authorship: Credits on the home page include Wolfram Grajetzki, Stephen Quirke, Narushige Shiode and "invited contributors." The primary sponsors include University College London (UCL), their Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis (CASA) and the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. The Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) funded the project.

Site host: University College London.

Peer review, permanence: There is no mention of peer review or long term availability on the site. The list of sponsors, however, provides a level of confidence in the underlying scholarship of the material presented. The absence of a mention of long-term availability and archiving is more troubling.

Site maintenance: There is no mention of site maintenance and the latest copyright date that I found on the pages was 2003. There is an email link to Stephen Quirke of the UCL and the Petrie Museum; he is listed as the site manager from 2000 to 2003. No one is listed as a current site manager.

Scholarly resources have two important components that need to be evaluated - the intellectual value of the information and the organization of that information. The web makes their separate contributions more intertwined, and usually a web site review will concentrate on one or the other aspect. Reviewing content takes a different knowledge base than reviewing the structure and organization. However, both aspects are important and need to be assessed. Excellent scholarship can be overwhelmed by a site's poor organization; conversely, a brillantly organized site can disguise weak scholarship. I will attempt to address both the content and the structure of these two web sites. Then I will provide an example of using them to understand a specific Old Kingdom monument.

I decided to review these two sites together because in some sense they complement each other. Digital Egypt for Universities contains pages devoted to a general overview of Egyptian culture from 4000 B.C.E. to 1919 C.E. with a concentration on the ancient period. The discussions are based on W. M. Flinders Petrie's work in the late 19th through early 20th centuries and on the Petrie Museum's post-World-War-II excavations, but they incorporate a broader vision of Egyptian culture than a single individual's or institution's excavations could supply. In other words, it has a broad chronology and range of topics, but a limited number of examples. In constrast, The Oxford Expedition to Egypt, Scenes-details Database, hereafter OEE scenes, takes as its subject images of specific type found in Old Kingdom tomb complexes; it includes all published Old Kingdom cemeteries, regardless of excavator or date of excavation. Its coverage is chronologically and topically narrow, but it includes all known examples.

These web sites are examples of two types of resources that are useful for scholarly research - (1) syntheses that present the results of a scholar's research and (2) raw data with minimal interpretation. As a general resource, the topical discussions presented on Digital Egypt are wide-ranging, representing the current state of knowledge about ancient Egypt. As a database the OEE scenes provides no analyses, only accessible, extensive, reliable data on which to base understanding. It is by combining the results of past research (Digital Egypt) and raw primary data (OEE scenes) that deeper research is possible.

The content of Digital Egypt is organized into the following topical areas:

The OEE scenes provides a database of scenes from Old Kingdom tombs with documentation on the terminology and abbreviations used, an extensive bibliography and a map. Images chosen are from 15 major groups and hundreds of subgroups. "Scene types and their scene details were selected as the primary subject matter of Phase One of the OEE Database because they are easily identified, and they constitute the most varied source of information for academic and non-academic research."2

A PDF file which lists all the subcategories runs to 27 pages! The major categories with a partial list of subcategories are:Both the types of images included and those excluded in the OEE scenes are clearly laid out on the introductory page.3 The arbitrary nature of the images included and excluded does slightly curtail the site's usefulness as a database. However, even with this limitiation, the OEE scenes is a magnificent resource and contains information on thousands of images.

The basis for the data presented is Bertha Porter and Rosalind Moss, Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings, (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1927-) -- Porter and Moss. These data have been augmented as the project has grown. Currently data are present for 495 tombs in 58 cemeteries at 27 sites.

OEE Scenes offers its data with no interpretation of the scenes beyond the subject classifications; however, as with any database, it provides a number of ways to organize its catalog of scenes. The introduction to the database provides an overview of the types of queries that are available and the displays that they produce. Line drawings of typical scenes from each subgroup are provided.

Both sites (Digital Egypt and OEE scenes) provide extensive data with adequate documentation and bibliographies to make further, more focused research possible. There may be more overt scholarly interpretation present on Digital Egypt, but that is the nature of the general site versus a database. The scholarly research that resulted in the categorization of tomb imagery on the OEE database is more basic, but no less important to our understanding of ancient Egypt. It is this type of research that supports the articles found on Digital Egypt.

Both sites are relatively straight-forward and simple to navigate. Both provide a banner with a menu of the main sections across the top of every screen.

The banner menu on Digital Egypt lists only the home page, the timeline, maps, the A-Z index and the learning page, but no search mechanism. All topical analyses are accessed from the home page. Each topical section within Digital Egypt has a different presentation of its material. Some sections, like astromony, are divided into topics (clocks, zodiac and astrolabes in the case of Astronomy) then into chronology. Others, like Beliefs, are first divided by chronology, then by topic. Cross-links on a page are only to other pages within the given section or to the bibliography. The Art-and-architecture section in particular has many internal cross-links so little backtracking is necessary to follow a train of thought not directly addressed by its authors. Other sections, like the Temple section under Beliefs, does not even provide cross-links to actual temples, even though Flinders Petrie excavated and published those at Thebes and Digital Egpyt itself has pages devoted to them. However, the extensive A-Z index can be used exactly like an index in a standard scholarly publication to access any data on the site. The A-Z index is also the only way to access much of the individual site information directly.

The banner menu on the OEE scenes site provides links to the introduction, overview, database, bibliography, glossary and help pages. The database page provides structured access to the data and gives a wide selection of ways to display the results of queries.

There are two hierarchical ways to approach the data, either (1) by a single tomb and all the catalogued imagery therein or (2) by a particular scene and all tombs that contain that scene. These hierarchic approaches have the frustrations inherent in this database structure. The data must be approached hierarchically, as the designers themselves used and envisioned them. In this case, attempts to see all images that a set of tombs might have in common involves manually comparing lists of tombs and their images or lists of image types and their associated tombs. Such lists are quickly produced, but it would be nice to be able to do the comparisons mechanically since that it what computers do very well. I do not know if the problem is with the heirarchical design of the underlying database or only with the provided approaches to the data that the web site allows.

Both sites fail in some aspects to take advantage of the possibilities of the new flexible and non-linear approaches to data that online resources provide. Both do, nonetheless, contain reliable data and interpretations that can be accessed in a logical order.

Both Digital Egypt and OEE scenes are so extensive that I decided that the best way to get a feel for their usefulness was to research a single Old Kingdom tomb complex. Both Digital Egypt and the OEE scenes give a list of Old Kingdom cemeteries and tombs covered by the site. The tombs listed on Digital Egypt are only those excavated by Petrie or the Petrie Museum; the OEE scenes has a less obvious filter for the tombs that it includes: its range of image types. Less elaborately decorated tombs, for example those with just depictions of the tomb owner, are not there.4

Only 4 tombs were included on both sites:

Fig. 1 - Plan of mastaba 16, Meydum, from the Digital Egypt site.

First the basic facts about the mastaba. The OEE scenes states that it contains two tombs described in Porter and Moss: (1) IV.92-3 and (2) IV.93-4. Dates are provided for the Nefermaat chapel and grave (Dynasty IV, Early to Middle Snefru) and for those of Atet (Dynasty IV, Middle Snefru). Digital Egypt gave 13 sources as a bibliography without mentioning the publication that underlies the OEE scenes, Porter and Moss. The copyright dates on the Digital Egypt web resource list predates the online version of Porter and Moss; however, I would have expected the print version to be included.

Neither site has photographs of the mastaba itself. The OEE scenes pages have only line drawings of generic representations of scenes included. Digital Egypt has photographs of some of the reliefs and small objects found, but none of Meydum, mastaba 16, the chapels or the tomb chambers. I think that for a web site aimed at undergraduates this is a major oversite. Of course, an image search on Google can provide numerous tourist photos of the site. My search (Nefermaat mastaba) turned up photographs of the Meydum cemetery, the mastaba and its chapels' friezes.

The Digital Egypt site gives a plan and a 3d reconstruction of the exterior of the final phase of the mastaba. It gives a brief history of the building phases, but the discussion is somewhat sketchy as to dating and interpretations. There is an extensive bibliography of print sources that should supply this information. The plan is interactive and a simple series of clicks will show the imagery and heiroglyphics on each wall. The mastaba includes 2 chapels with their respective tombs.

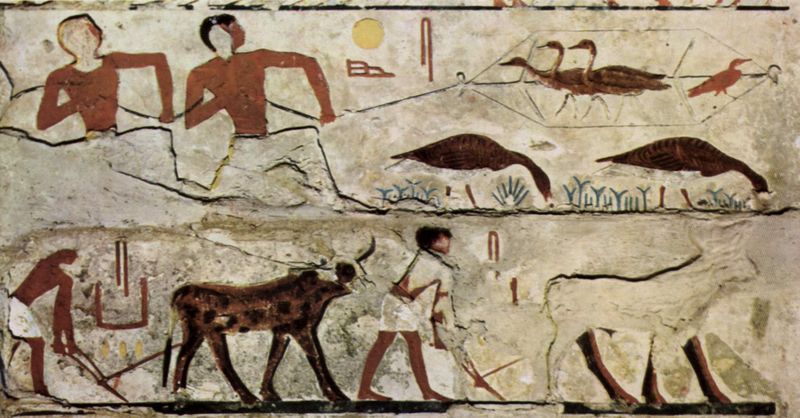

Nefermaat�s tomb and chapel: Digital Egypt shows a tomb portrait of Nefermaat surrounded by hieroglyphics of his titles and family lineage, along with their translations. (The technique used to create the wall images is described on Digital Egypt pages.) Fragments of this wall panel are in multiple museums and the Digital Egypt page gives the current location and acquisition number of each fragment as the cursor moves over a drawing of the image. The OEE scenes does not include this type image (a simple, seated portrait of the tomb�s owner), but many other wall images are included in the OEE scenes -- scenes listed include a bird netting scene and a plowing scene. Note that neither site gives an inventory of all wall decorations in the chapel and tomb.

Atet's tomb and chapel: This tomb complex is located within the same mastaba and contains both bird-netting and plowing scenes in its wall reliefs. These, like Nefermaat's, are distributed among several museums. The fragment with the bird netting and plowing registers are in the Cairo museum (Cairo JE 43809). Since these two scenes from the Atet chapel are together on the same relief fragment I have illustrated the Atet reliefs the figures below.

The bird-trapping scenes from the two sites are displayed in figures 2 and 3.

Fig. 2 - OEE scenes generic sketch of an Old Kingdom bird netting scene.

Fig. 3 - Digital Egypt image of bird-netting scene in the Atet complex of Mastaba 16, Meydum.

The second register from the bottom, right shows bird-netting,

below it the plowing scene.

Fig. 4 - A photograph of the relief in the Cairo Museum, image in the public domain.6

Figure 5 - OEE scenes generic sketch of Old Kingdom plowing scene, a detail from the

argicultural activities scenes.

Once I knew the architectural context of the 2 chapels and their images and decided to investigate further the bird netting scene, I turned from Digital Egypt to OEE scenes. There, a query for bird netting scenes resulted in a display of 94 tombs along with the cemetery and several bibliographic references for each tomb. Both the tombs of Nefermaat and Atet were among those listed. Each listed tomb can be brought up to see the details of its date and a list of all scene-types recorded in the database for that tomb. These resulting data sets can be printed out in list format, but not stored temporarily for further queries; nor can they be downloaded.

These lists highlight a disadvantage of hierarchically structured data. You can not in a single query find whether tombs share multiple scene-types. Obviously a sequence of queries will get you the data that you are looking for, each query producing a list that can be scanned manually to obtain the requisite data. This is better than having looking in publications listed in the Porter and Moss and then finding a library that has them. The compound query that I posed can be answered by physically examining the lists produced by the available queries, a procedure any researcher takes for granted using more traditional sources. It is more convenient to use the database than a numerous publications to gather the lists, but the idea of manually comparing lists from the same database seems regressive.

I returned then to Digital Egypt to investigate bird netting and plowing in Old Kingdom Egypt. I found photographs of actual nets and plows to supplement the tomb imagery. The web site also contains discussions of the agricultural calendar for grain, food production in general and animals that were hunted and trapped. Between the lists of specific tomb scenes for these two chapels in OEE scenes and the general information found on Digital Egypt, it is possible to get an excellent understanding of the activities shown on the tomb walls.

As to grave goods, the tombs as excavated by Petrie had been disturbed in antiquity, so there were few found. Digital Egypt does have images of pottery fragments found in Atet's burial chamber from the Petrie Museum's collections. There were no other types of artifacts mentioned.

The two web sites under review produced a fairly complete understanding of this mastaba, and provided enough data to continue research as time and inclination allow.

My research project to understand mastaba 16 at Meydum proved to be useful in understanding the strengths and weaknesses of the two sites under review -- Digital Egypt and the OEE scenes. These two sites provided a wealth of data and adequate bibliographies. The frustrations were minimal, and together they provided reliable scholarly data appropriate for undergraduates as well as a solid beginning for more advanced study with the aid of their extensive bibliographies. I highly recommend both sites.

-- Susan C. Jones

1. Several months ago with an ADS site, archiving would not have been a concern, but funding for the ADS has become uncertain. The discovery of new Old Kingdom tombs that would need to be cataloged occurs at such a glacial pace that updating issues are not necessarily a major concern. Return to text.

2. "Oxford Expedition to Egypt: Scenes detial database. Introduction," copyright ADS 1996-2008, accessed on 8 Feb 08. Return to text.

3. ". . . not included in the current database: processions of bearers carrying offerings; lines of estate personifications with gifts from productive lands; individual priests and scribes performing their duties; representations of the tomb owner and family members; figures of officials, servants amd household pets; species of animals, amphibians, birds, fish and plants; hundreds of man-made and natural objects and hierglyphic inscriptions too numerous to count." Introduction to the database, accessed 20 Dec 2007. Return to text.

4. See note 3. Return to text.

5. The Electronic Tools and Ancient Near Eastern Archives (ETANA) has put online the complete volume of Meydum and Memphis (III), a 1910 publication by Flinders Petrie, et al, as a PDF file, http://www.case.edu/univlib/preserve/Etana/meydum_memphis3/title.pdf. This work includes the final excavation report on the mastaba of Nefermaat and Atet. In addition, the University of Pennsylvania has also begun to put up information on their 1929-31 exploration of the Meydum. Unfortunately, I could not access some of links on that site, http://www.museum.upenn.edu/new/exhibits/online_exhibits/egypt/meydum.shtml. Furthermore, a simple google search on Meydum or Nefermaat Mastaba will produce many references. The mastaba is extensively written about and photographed since the area of the mastaba dedicated to Atet is the origin of the famous images of Egyptian ducks. Return to text.

6. This particular image was found at http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Egyptian_Museum, accessed 23 January 2008. Return to text.

For an index of other CD and Web site reviews available on the Web pages of the CSA Newsletter, see the review index.

For other Newsletter articles concerning the use of electronic media in the humanities, consult the Subject index.

Table of Contents for the Winter, 2008 issue of the CSA Newsletter (Vol. XX, no. 3)

Table of Contents for all CSA Newsletter issues on the Web

Table of Contents for all CSA Newsletter issues on the Web