|

Susan C. Jones

(See email contacts page for the author's email address.)

The Internet History Sourcebooks Project (IHSP)

Authorship: Dr. Paul Halsall and others. Mr. Halsall is the originator and sole editor of the site since its inception in 1996.1

Site host: Fordham University.

Peer review: Peer review is not mentioned. Much of the material has been previously published; peer review, therefore, is not expected. Pages devoted to historical methodology and how to use the web site are by the editor and have presumably not undergone peer review. Similarly, one would not expect peer review of new translations made for the site or secondary commentaries by Halsall.

Permanence: There is no specific mention of long-term availability on the site. However, both the History Department at Fordham and its Center for Medieval Studies make statements about the importance of the IHSP for the study of history, implying institutional support for the project.

Site maintenance: No mention of policies in this area. Several pages make reference to a major update of links started in 2006 for the medieval portion of the IHSP, but there is little evidence of it or any recent maintenance. Each page is date stamped with its last update; the most recent dates I found were 2007 on a page in the medieval and GBLT sections. The onsite primary source material requires little maintenance; so there is no reason to assume that such pages would have required updating after they were originally uploaded. For indices of linked off-site sources, the required timing for periodic maintenance is unpredictable.

Archival Procedures: No stated policies; however, being hosted by a university, there is probably some form of backup. However, standard IT back-up procedures do not include archiving.

Languages: Primarily English. All primary sources have English translations and all secondary sources are written in English. In addition, a few primary sources are provided in the original language.

The Internet History Sourcebook Project (IHSP) is an ambitious one with a worthy goal -- to provide free, digital access to English translations of important primary sources for the study of history. Access in this case means either on-site pages with original translations or links to other sites with translations that are in the public domain. Mr. Halsall went on to supplement these translations with a combination of on-site pages and links to off-site primary documents in the original language, secondary sources in English and other resources for the teaching of history and historical research to undergraduates.

This is an incredibly large, complex project and it led to a large, complex website. I have not, indeed could not have within the limited time available, examined every page on the site. For this review I confined myself to presenting my impressions after scanning the general contents and closely examining three specific areas -- the ancient world, women's history and gay-lesbian-bisexual-transgender history. These areas were chosen because of my professional activities and personal interests and do not reflect any emphasis given them by the site itself. Mr. Halsall's training and teaching experiences are in the areas of medieval Europe, China and gendered history, so that there is probably greater depth and closer monitoring in these areas.

The project was conceived circa 1996, a period of great optimism for the future of a free digital "information highway." A commonly held assumption from that period was that the internet was a permanent, free public repository for knowledge. Economic realities have proven this to be an unachievable ideal, although it is still held by many internet users. Other ideas of the time (the willing participation of expert, unpaid volunteers and free resources to initiate and maintain the information) were obviously overly optimistic even at that time. The fact that the IHSP still exists is a credit to both its editor and the underlying ideal of free, easily accessible resources. It has remained true its founder's vision and maintained its clear basic presentation free of advertising.

One further note, the IHSP was developed before the advent of modern search engines such as Google.2 In 1996, a web site primarily consisting of links to other web sites with a common theme was not the dinosaur that it may seem to be today. Even though today the primary resources (including those incorporated within the pages of the IHSP) can be found quickly with Google, I find value in the scale and organization of the IHSP's myriad links.

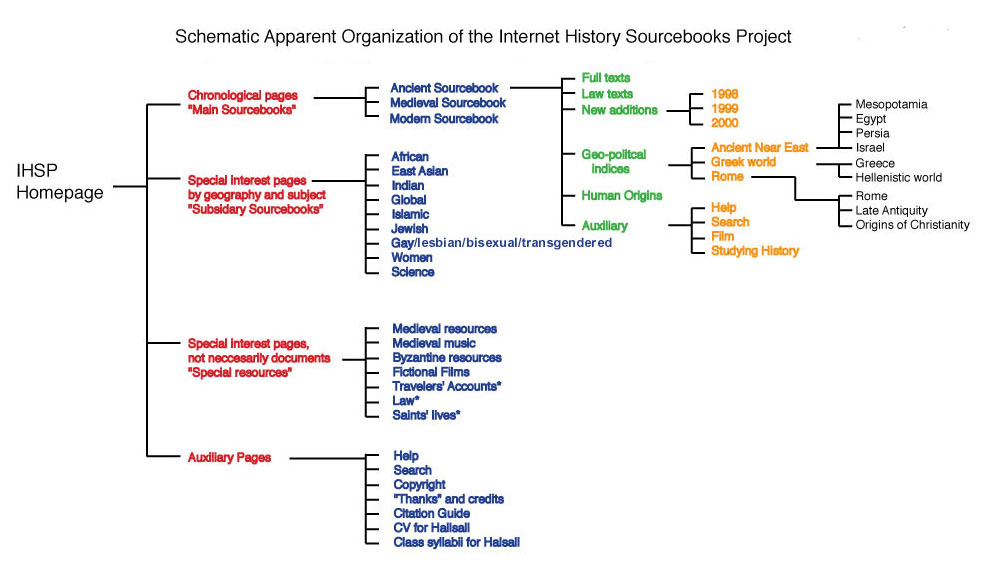

I constructed simplified "organizational" charts to facilitate an understanding and scope of the organization of the site. Halsall has taken complete advantage of the non-linear properties of websites; so any attempt to produce a 2-dimensional chart of the site is doing a disservice to both the site and to him. He has divided the pages of the site into two types: (1) "content" pages, that is, pages that are documents, and (2) "index" pages, that is, pages that provide links to "content" pages and information about the site. He has provided three different access paths to the underlying "content" pages -- chronological, geographical and by specialized subject areas. Menus across the top and in the upper left corner of each page provide links to the main page for each division within these three classifications. Thus, there are multiple cross-links providing multiple paths to any given page. Halsall provides a navigation path to the homepage to orient the reader, and to negate the feeling that it might be impossible to relocate to a given resource after the passage of time. He also lists the web site address of each link provided. For example, there are two separate links to Hesiod's Theogony, one "at this site" and one "at OMACL" (Online Medieval and Classical Library).3

Figures 1, 2 and 3 provide a better overview of the site organization than an exhaustive list of links and descriptions of the various pages. Figure 1, below, reflects my sense of the site of the organization of the chronological pathways, giving details only for sections of the Ancient Sourcebook. Figure 2 shows the organization of the special subject of women's history and figure 3 the organization of the gay-lesbian-bisexual-transgendered history pages. The organization of the latter differs enough from other sections of the site that it needs its own chart. Figures 2 and 3 can be found under Evaluations.

Figure 1 - The simplified organization of the IHSP web site. The diagram only shows the structure of the home page and the Near Eastern and Classical areas of the Ancient Sourcebook in detail.

This complex website was developed over a number of years and as Halsall gained experience and technology changed, he made changes to the details of the "index" pages. He did not necessarily go back to make these to previously posted pages. Similarly, he added features (icons showing the type of data on off-site pages) and abandoned others (listings of "recent additions"). None of the resulting inconsistencies interfere with the ability to navigate the site.

The site is not well maintained, and few new resources have been added in the last few years. The links to many off-site resources are broken; either their addresses have changed or they are no longer on the internet. Even if the address has changed, though, a Google search will usually turn up the current address. If Halsall knows that the pages are no longer on the web, but have been archived, he has updated the link to the internet archive site, archive.com.4 Unfortunately, even links to some archived pages are broken. The home page comments that a major overhaul of the broken links was begun in 2006, but it was never completed judging by the dates listed on the individual pages.

The Ancient Sourcebook: Much of the primary material comes from off-site sources -- The Online Medieval and Classical Library at UC-Berkeley, Perseus at Tufts, the MIT Classics Archive, Oxford Text Library at Oxford University, Electronic Tools and Ancient Near Eastern Archives (ETANA), etc. The same is true of many secondary resources -- Prof. Jeremy Rutter's Prehistoric Archeology of the Aegean, Prof. Kevin Glowacki's Ancient City of Athens and various articles at Perseus.5 Since all of these resources as well as those on the IHSP site can be found through other search engines, why use the IHSP? The reason is all in the organization and auxiliary material.

The IHSP and its Ancient Sourcebook are organized for teaching undergraduates with limited research experience in humanities. Besides the extensive English translations of classical texts, there are discussions of issues involved evaluating sources, plagiarism and writing research papers. It is handy to have a single scholarly web site with this range of didactic resources to give such students.

An examination of the links found under Greece shows them to be a combination of primary texts in translation, images and commentary by scholars in the various fields. It is nice to see that images and artifacts are included as primary sources. As an archaeologist, I applaud any recognition of material artifacts as primary sources by an historian, but here the reality does not match the intent. There are too few artifacts listed to be of consequence.6 Most of the images of artifacts and structures are from off-site links such as Perseus and Stoa.

Links are listed by chronology and subject matter. The advantage here is that the Ancient Sourcebook collects appropriate resources that an undergraduate might not think would be useful for a given topic. For example, resources for Greek Religion include the obvious -- Homeric hymns, Hesiod's Theogony -- and the not so obvious -- the Petelia inscription in the British Museum, Lysias's Against Nichomachos, Euripides's The Bacchae, Plato's discussion of the transmigration of souls from The Republic and several of Plutarch's biographies. The inclusion of such a variety of primary sources should suggest paths of research to students that they may not have discovered on their own. Halsall's extensive lists also are a quick check for advanced students to ensure that they have covered the most commonly used resources.

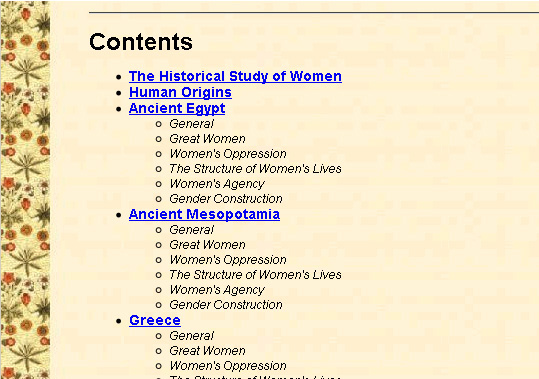

The Women's History Sourcebook: The next area that I examined was the Woman's History, one of the special subject areas. A section of its "index" page can be seen in figure 2.

Figure 2 - The beginning of the table of contents for the Women's History Sourcebook at the IHSP web site.

This and the other special subjects in the IHSP provide links to the same primary sources and onsite resources as the chronological pages. In addition, there are links to several secondary sources that are specific to the field of women's studies. These secondary sources are off-site commentaries on the evidence for the existence of the "Mother Goddess" and matriarchies in Europe and the Mediterranean basin during the Neolithic era.

The links found here also point directly to relevant passages in longer works, such as Herodotos' account of Artemesia at the battle of Salamis, and Procopius' accounts of Theodora in his Secret History.

The organization here differs from the Ancient Sourcebook in that it is by cultural division with a standard set of subject areas for each culture. This standard set is presented whether or not there are links to be found under each division. This approach is appealing because it is easy to navigate and easy for the editor to maintain as new resources are added. It also, however, presents an inflated idea of the linked resources.

The alternative categorization of links to the IHSP resources is a prime example of the non-linear organization that is possible with web pages. However, the navigational link provided within the onsite "content" pages to return to an "index" page only goes back to the main chronological indices -- ancient, medieval or modern. An unexpected consequence of this linkage is that users can place thoughts of and about women in their broader cultural context. Of course the browser's "back" button will reverse the pathway actually used.

A glance down this "index" page reveals the only links to visual materials are to photographs of modern women. I found this disappointing; many of the cultures covered in the sourcebooks have images of women and their activites. For instance, there are numerous Greek vases that depict both everyday women's activities and important mythological females. These images provide a more rounded picture of women's lives than the contemporary writings of elite Athenian men.

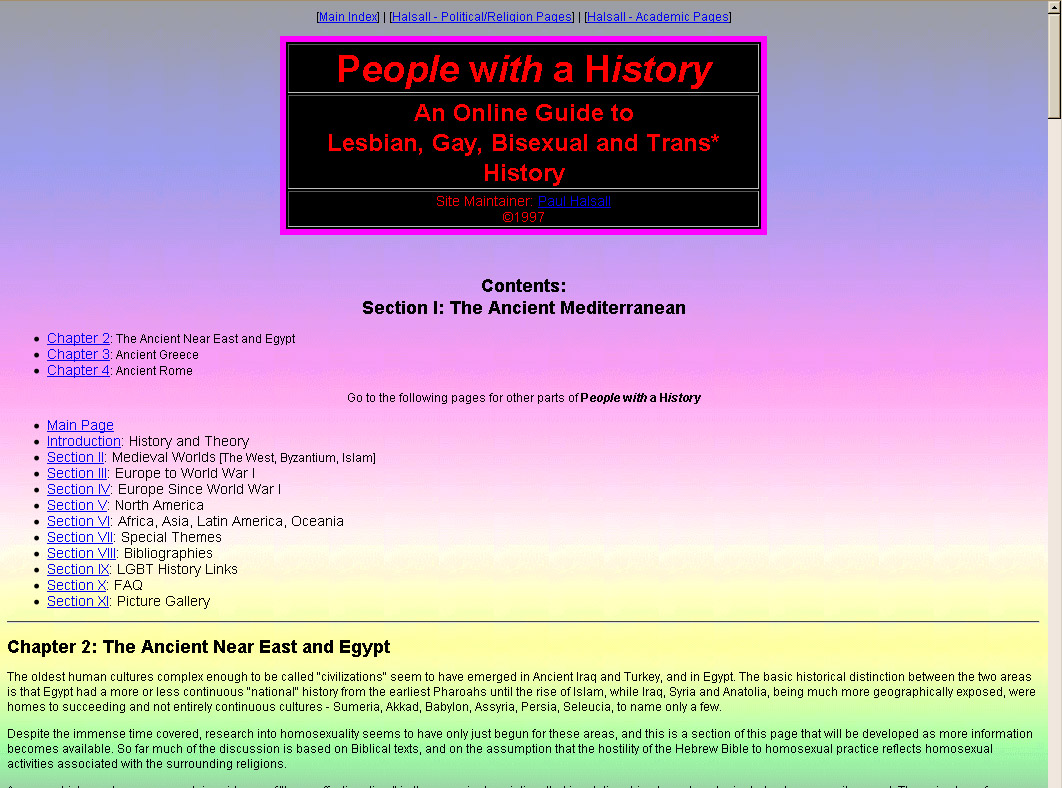

People with a History (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgendered) Sourcebook: The final area that I examined was another of the special subject areas; its basic organization can be inferred from the Table of contents from the Ancient Mediterranean section page as seen in figure 3.

Figure 3 - The header and opening paragraphs of the Ancient Mediterranean section of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgendered History links in the IHSP web site.

Figure 4 - A concatenated view of the organization of the Ancient Greece section of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgendered History links in the IHSP web site.

The material presented in this division has a greater proportion of secondary commentary to primary sources than other divisions. As this is not an area with which I am familiar, I cannot comment on the thoroughness of its coverage. For a neophyte like myself, it seems to be a comprehensive introduction to the subject and its issues.

The chapters of People with a History are arranged by geography and chronology, with links grouped by a combination of primary/secondary source and format -- discussion, reviews, texts, images, websites -- rather than subject. Note that not all cultural areas have links under all groupings. In fact, only Ancient Greece has links in all five; most have only discussions, texts and websites.

As is evident from figure 3, the background is a "rainbow" which I find both distracting and in direct contradiction to the stated design principle of plain, easy-to-read text. Another difference is the lack of links to "Help" pages that explain the basics of critical reading of sources and the primer of writing research papers. These links do occur on the introductory paragraphs of the Women's History Sourcebook. This is also the only page with a link to pages written by Halsall ("Halsall - Political/Religion Pages") for which a password is needed to gain access.

Again I looked primarily at the resources listed for Ancient Greece, -- Section I chapter 3. The links are presented with longer annotations than on other IHSP pages. There are more secondary sources and book reviews of modern scholarship than in the other chapters under People with a History. For example, there are BMCR reviews from its inception (1990), but only through 1996! With this particular widely-read publication, it is a surprising that the site has not been updated, especially since the latest update on the page is dated 2007. If, as I strongly suspect, it is too arduous to maintain a listing of relevant BMCR reviews, a simple statement to that effect should be made. There is a strong reliance on Perseus for both primary and secondary sources. Ancient Greece is also the only area that provides images and texts in their original language as well as an English translation.

My overall impression of People with a History is that it belongs to a different universe than the other divisions of the IHSP. These resources seem to be made to stand-alone and are not well integrated into the IHSP. I do not think that this is intentional, but I find it disconcerting and potentially denigrating to this area of gendered studies.

Overall, this is a remarkable site and one whose resources are invaluable to the teaching of undergraduate art history and history. The size and scope of the links provided are enormous. Halsall uses the nonlinearity of the internet to great advantage with numerous links among and between the divisions although the relative uniqueness of the People with a History division is jarring.

The advice on how to use the material provided, on textual criticism and on producing an adequately documented research paper is welcome and helpful. Such advice reinforces and reminds students of the fundamentals of good research and writing principles.

The task of maintaining the site with its many "off-site" linkages obviously means that there are more broken links than desirable but currently not an intolerable number. The divisions have not all been maintained at the same frequency while revisions to content are primarily additions without necessarily editing the original or integrating the newer material seamlessly. I do not find this a major flaw. However, it does make going between divisions more difficult than expected. I find the IHSP's main value is as a single site with annotated listing of online resources whose content has the stamp of academic approval.

At this point in time, maintenance of the site is inadequate and exclusively concerned with updating the links to external sources. As time goes on, more of these links will become outdated and finding the available primary resources will require the use of efficient search engines like Google or Bing. Experience suggest that over time the site will become a less and less useful tool as more links become outdated. On the other hand, the principles of good scholarship, as evidenced by the contents of the auxiliary pages on the processes of research, will not change, nor will the need to use primary and secondary resources and the thought processes stimulated by categorical listings of them.

In prefect hindsight, for the IHSP to continue to be useful for the indefinite future, it would be necessary to redesign it so that it requires no maintenance. Such a redesign of the IHSP should accommodate (1) the relatively static nature of pages on scholarship and the lists of suggested resources to be consulted7 and (2) the volatile nature of specific hyperlinks to primary and secondary sources. The static pages need no redesign; they do not currently require maintenance. The volatile hyperlinks require constant attention; here is where the redesign necessary. A simple suggestion would be for the hyperlinks to be generated by a pre-programmed applet that issues a call to a sophisticated search engine rather than having links hard-coded into the pages. In other words, the author/title/subject of the resource needs to be listed on the IHSP page, but the actual link would be generated by an applet when the user clicks it. Generating the most effective text string for the search would be the hard part. My searches always produced the wanted results, but usually not among the first 10 hits. More systematic experiments should yield better results and provide a pattern that would make it possible to replace the hard-coded links.

In summary, this is a valuable site, and its intractable size is handled well. Some of its original goals have been made irrelevant by 13 years of technological innovations, but its pedagogical and didactic value remains high.

-- Susan C. Jones

References

1. "Dr. Halsall began the Sourcebooks in 1996 and graduated from Fordham in 1999. He remains the author of the Sourcebooks and retains copyright on the specific electronic form, modernized versions of any texts and any notes. He is also the sole editor of the pages. The Internet Medieval Sourcebook is published by the Center for Medieval Studies; the remaining Sourcebooks are published by the Department of History at Fordham." (http://www.fordham.edu/history/Links/histlinks_IHS.shtml; accessed 13 Feb 2009; no copyright date.) I have cited only web addresses in these footnotes. If you wish to locate the information within the online page, you must use the "find this text" function of your browser. Return to text.

2. Google was incorporated and registered as a domain name in September, 1998. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Google, accessed June 3, 2009; copyright June 2, 2009.) Return to text.

3. The Internet Ancient Sourcebook (http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/ancient/asbook07.html, accessed June 3, 2009; last revision 2/23/2007.) Return to text.

4. Discussion in the CSA Newsletter has focused on archival issues associated with web pages before. Issues with maintaining current and past versions of a given page raised by Mr. Eiteljorg in his recent article, "What Data Will Be in Use Tomorrow?," CSA Newsletter (XXI.3; January, 2009) at csanet.org/newsletter/winter09/nlw0905.html, should not be major concerns here. These sought-after pages contain mostly out-of-copyright (i.e. over 75 years old) printed material; changes to their content should be non-existent. Return to text.

5. Mr. Rutter's site was been reviewed in the CSA Newsletter. See Website Reviews: The Prehistoric Archaeology of the Aegean by Susan Ferrence (XX.1; Spring, 2007). Mr. Glowacki's site, while still in its very early stages, was more briefly discussed in "Image Collections on the Web -- Exciting but Still in Their Infancy" XVII,2; Fall, 2004). Return to text.

6. Halsall justifies the inclusion of images and audio recordings of ancient texts in the original language, "since art and archeology are far more important for the periods in question than for later history." (http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/ancient/asbook.html; accessed 3 June 2009). Return to text.

7. The list of primary and secondary resouces online will grow over time, eventually making some maintenance required. However, the task then becomes managable since the editor's own research and pedagogic needs should provide the necessary information. Return to text.

For an index of other CD and Web site reviews available on the Web pages of the CSA Newsletter, see the review index.

For other Newsletter articles concerning the use of electronic media in the humanities, consult the Subject index.

Next Article: Susan C. Jones, With Thanks.

Table of Contents for the September, 2009, issue of the CSA Newsletter (Vol. XXII, no. 3)

Table of Contents for all CSA Newsletter issues on the Web

Table of Contents for all CSA Newsletter issues on the Web