|

Surveyors using a total station have developed codes for specific kinds of survey points, and they are generally working with well-known requirements that limit the number of points required. On some occasions, they are taking many points to create a topographical map, but those points need not be identified as belonging to a specific block or, worse, a specific point on a specific block.

Archaeologists working as the CSA Propylaea team, on the contrary, must know not only the coordinates of points; they must also know what point on which block is defined by a given set of coordinates. It may seem that the geometry would always be clear, making the relationship between coordinates and block location unnecessary, but that is not true. As the example in Fig. 1 shows, it is quite possible to have survey points that are ambiguous as to the block or point on the block from which they originate. In the example shown, three different configurations from the basic survey data have been shown; a fourth is possible. Four different versions of the blocks could thus have been created simply by differently assigning the four points numbered 3 through 6 in this simple example.

|  |

Fig. 2 - Left: Points 3 and 5 assigned to the left block (red) with points 4 and 6 assigned to the right block (black). Right: the resulting blocks.

Fig. 3 - A second version of the blocks with points 4 and 5 assigned to the left block (red), 3 and 6 assigned to the right block (black).

Fig. 4 - A third version of the blocks with points 3 and 6 assigned to the left block (red), 4 and 5 assigned to the right block (black).

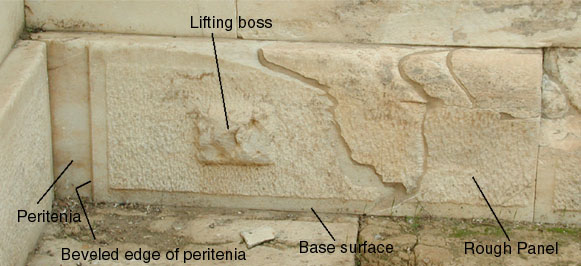

The example is very simple compared with reality. In the case of the Propylaea, for instance, many of the individual blocks were extremely complex, having primary surfaces, peritenia bands, rough bands, rough panels, cuttings, and lifting bosses. As a result, the note-taking process is critical. Although I had attempted to create a note-taking scheme for this, the complexity of the blocks overwhelmed that scheme. Chrys Kanellopoulos' drawings were more clear than the notes in many cases, but they were also time-consuming to make, especially since he was not close to the blocks he was drawing.

Fig. 5 - A complex block from the east wall of the NW wing of the Propylaea.

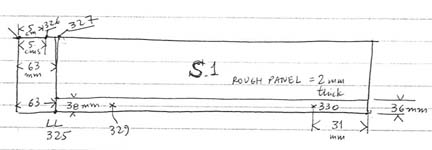

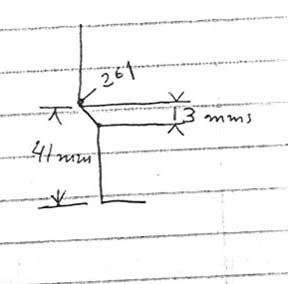

Fig. 6 - One of the drawings made by Mr. Kanellopoulos to indicate which points had been surveyed, or measured by hand.

Fig. 5 - A margin drawing made by Mr. Kanellopoulos to clarify text notes.

Because different projects will present significantly different problems with identification of survey points, no detailed advice can be provided here that will suffice for all work. It is clear, however, that the note-taking process should be carefully and thoroughly planned, updated, and checked to prevent accidental confusion. It is also important that there be regular checks of the notes to be sure they are consistent and unambiguous.

Note that small edits were made in this article on 1 June 2009, one to correct a tense error and one to remove a word that should not have been included.

For other Newsletter articles concerning the The Propylaea Project or applications of CAD modeling in archaeology and architectural history, consult the Subject index.

Next Article: Email Files Again

Table of Contents for the Winter, 2004 issue of the CSA Newsletter (Vol. XVI, no. 3)

Table of Contents for all CSA Newsletter issues on the Web

Table of Contents for all CSA Newsletter issues on the Web

| Propylaea Project Home Page |

CSA Home Page |