| Vol. XXV, No. 2 | September, 2012 |

Articles in Vol. XXV, No. 2

Artifacts and Applications: Computational Thinking for Archaeologists

A new way to think about data.

-- Andrea M. Berlin

Digital Infrastructures for Archaeological Research: A European Perspective

Repositories throughout the world.

-- Julian D. Richards, Director, Archaeology Data Service, UK

Digital Data in Archaeology: The Database

Real-world examples show mixed success.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

§ Readers' comments (as of 10/22/2012)

Website Review: Mediterranean Archaeology GIS (MAGIS)

A good website waiting for more data.

-- Andrea Vianello

There Is a Difference

Digital infrastructure services are not the same as archival services.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

To comment on an article, please email

the editor using editor as the user-

name, csanet.org as the domain-name,

and the standard user@domain format.

Index of Web site and CD reviews from the Newsletter.

Limited subject index for Newsletter articles.

Direct links for articles concerning:

- the ADAP and digital archiving

- CAD modeling in archaeology and architectural history

- GIS in archaeology and architectural history

- the CSA archives

- electronic publishing

- use and design of databases

- the "CSA CAD Layer Naming Convention"

- Pompeii

- pottery profiles and capacity calculations

- The CSA Propylaea Project

- CSA/ADAP projects

- electronic media in the humanities

- Linux on the desktop

Search all newsletter articles.

(Using Google® advanced search

page with CSA Newsletter limit

already set.)

Website Review: Mediterranean Archaeology GIS (MAGIS)

Andrea Vianello

(See email contacts page for the author's email address.)

MAGIS: Mediterranean Archaeology GIS

- URL: cgma.depauw.edu/MAGIS/

- Authorship: Principal Investigators: Rebecca K. Schindler and Pedar W. Foss. Co-Principal Investigators: Michael Galaty, P. Nick Kardulias, and Kenneth S. Morrell. Technical support: M. Beth Wilkerson and Alex Iliev.

- Site host: DePauw University.

- Peer review: None stated.

- Permanence: No explicit information, but it has been available for nearly a decade now.

- Archival procedures: None stated for the website.

- Languages: English.

Preface

There was a time when the Internet was mostly the domain of geeks and academics, the future looked brilliant and new ideas could shake any virtual establishment. As time passed, the Internet grew and became a virtual forum for people from all places and walks of life, losing its exclusive character. Nowadays the Internet has the same many shades of grey that the real world has. Looking back to nearly two decades of being an Internet user, I have become used to embracing new developments very quickly and not caring what had served me well until then. The on-going philosophy is "new is always better." When it comes to contents, websites in this specific case, I am afraid that the same attitude appears to have been followed by almost everyone, including academics. When something is written online, people either assume that something better will be written in its place or that it will stick forever in some corner of the Internet. In fact, when something is published online, it is very likely to disappear without a trace. Internet users have very short memories; so nothing needs to stay for very long, and something new and better is always coming. This is fine for the commercial Internet and the social media networks, but for scholarly needs and concerns, the Internet is proving to be a challenging and inhospitable place. In particular, for academic work accessibility and permanence are critical issues. Many projects have been put onto the Web with great promise and substantial funding but then abandoned to the digital vacuum. This month alone the prestigious journal Nature reports that "the US National Library of Medicine (NLM) are threatening five widely used biological databases" due to funding cuts. (See www.nature.com/news/databases-fight-funding-cuts-1.11347, last accessed 24 September 2012.) They are not directly closing the databases, just cutting the funds, but the end-result will be the closure and possible disappearance of the databases. That's right: all the hard work and money spent on these projects may be gone by the time that you read this review, and to get them back would require an equal, perhaps larger, effort to create similar databases.

The Website

The Mediterranean Archaeology GIS (MAGIS hereafter) is an archaeological database that uses the power of mapping to present important data. It was funded by a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation from 2002 to 2007. Like many other websites, it could have disappeared by now, but it is still here (at the time of this review), although it was last updated in October of 2011 (according to the home page), and still displays a note in red, reading "MAGIS is a work in progress." The interface is neat and adapts very well to most browsers and screens, though it works best with Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox.

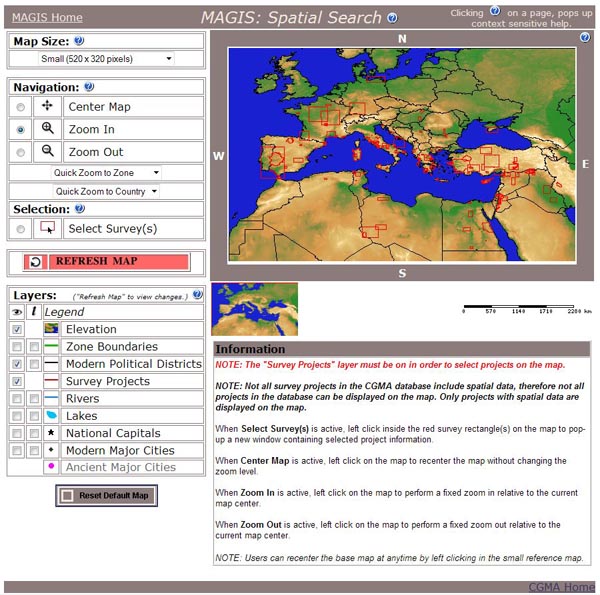

Just below the logo and heading, there are six "buttons" on the home page (Fig. 1), clickable images that provide easy access to the relevant sections. The central part of the home page describes the options and provides a helpful and concise guide, which is further extended in the "Help" section. Further down the home page there are the credits and even access to the site statistics. (The last update in 2010 suggests that a respectable 1,000 queries a month on average were performed on the database.) The red note in the heading is somehow the only piece of the home page that I do not like: it proudly states that 381 projects have been inserted, but it makes me think of a database in its infancy rather than a mature product. I think It would be better moved onto the "Spatial Search" page, which is the page that most real users will access and bookmark.

Fig. 1 - Spatial search page in MAGIS.

Click here to see the image at full size

in a separate window.)

This section is the real heart of the website and uses advanced mapping tools to mirror the typical work experience that a full GIS package would provide. The "extra large" map (selectable from map size) of the whole database is also a beauty to behold: only then does the scope of the database become really clear. Unexpectedly, some projects are relatively far from the Mediterranean: there are projects in the Sahara desert, Nubia and Egypt, the Black Sea and even Germany as far north as the Baltic Sea. The database is not without formal errors: clicking on southern Germany also pops-up a list of projects in Saudi Arabia. There are also a few misspellings, such as in the project name of the Saudi Arabian survey (Fig. 2). A further observation on the general quality of the database is the overemphasis on American- and British-led projects. For example, very little is mentioned of the work of most foreign schools in Rome and Athens (a swift check of their online websites would suffice). The linguistic barrier is a mighty dividing wall here.

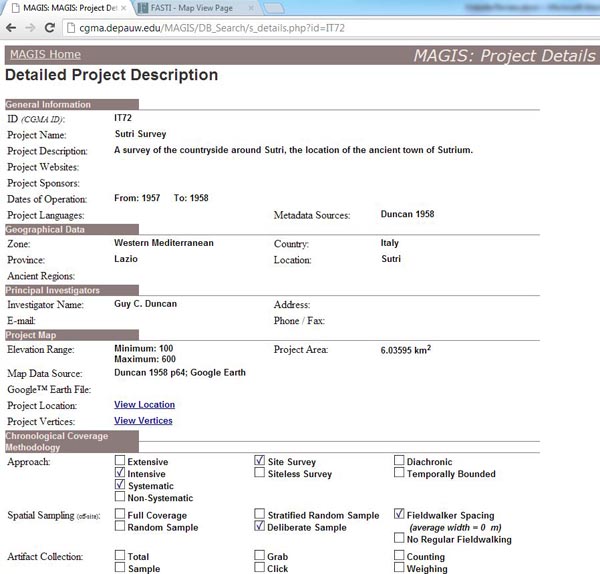

Figure 2: Data search in MAGIS.

Click here to see the image at full size

in a separate window.)

The Google Earth Browse option only reminds me how pervasive the presence of Google has become. This implementation, however, uses XML in the form of a KMZ file and would be compatible with other applications supporting that format. Although the website states that you need to download a piece of software, in fact, you can copy the link and paste it right into Google Maps to access a working online interface. This option, especially when using the most compatible of browsers, Google Chrome, works best. Yet, many other combinations would work, and if Google were to disappear overnight, then the work published here would still be accessible, either using the internal interface or alternative web mapping tools. The Database Search provides a third option to access the database, the textual search. It works and the website is responsive. Given the nature of the website, this may be the least useful of all access modes, but I am happy to see it not forgotten.

The project descriptions are also very commendable in their format and scope. Both surveys and some excavations are included. There are links to websites as well as bibliographies. The typical page returned from results (Fig. 3) is well thought-out, clear, concise, readable and comprehensive. Yet each project is a case apart because some projects are only partially described (i.e., not all fields have data). The one thing that seems to me conceptually flawed is to publish online, in textual format, emails and phone numbers (albeit office details) of those directing the projects. I would prefer to see such information protected in some way, even if freely available on the Internet elsewhere. Most of it is at this point probably outdated, but future entries should not include such information so casually unless the interested people have explicitly agreed to have this information posted online.

Figure 3: Typical data form for MAGIS (partial view).

Click here to see the image at full size

in a separate window.)

Data Entry allows, after a simple registration, one to add one's project into the database directly. This is a very good decision. Section "Help" is very useful and comprehensive, detailing all aspects of using the database. It contains many images too, which simplify consultation. I sighed after reading it, thinking how useful this database would be if it was made somehow mandatory for projects to add their information.

A Comparable Website

A comparable website exists: Fasti Online [http://www.fastionline.org/]. Although this database is very selective (it targets projects concerning the Roman Empire only), it encompasses a similar geographic region as MAGIS. Fasti Online's interface makes greater use of multimedia, but the records are poorly thought-out since they only include a short description of the project (without any template), for each season, the names of project directors and an optional bibliography. The mapping tool uses Google Maps to display the results, effectively making accessibility to the website dependent upon the continued availability of that service. Thanks to agreements with governmental agencies, comprehensive data are available, but only for those countries where agreements are in place.

Conclusions

This review follows by a few years another review of the website, which resulted also in the production of a podcast with Prof. Pedar Foss (see www.intute.ac.uk/podcasts/), one of the lead authors of the project. I still remember the high hopes expressed then (2007), and the enthusiasm for GIS. Readers can still listen to that interview. The choice to review MAGIS now is based on three main considerations: to review a good website, to see what happened to a promising project five years on, and to consider the utility of online mapping tools (Web GIS) for archaeological websites. MAGIS proves to be a rigorous website, carefully designed and admirably engineered to deliver key information in the easiest way possible. It embraces open standards without shying away from commercial technologies, finding the right blend. The database is large enough to be useful as it is, but it is worrying that it has not been developed further in terms of contents. This would be an enormously useful website if it could achieve the comprehensiveness reached by Fasti Online for some regions.

Lessons can be learned here. It seems evident to me that funding bodies have no long-term policies in sight when financing such projects. This short-sightedness may be acceptable for commercial projects, but is unacceptable for research projects. MAGIS the database is now ready, but few seem interested in providing data. Agreements such as those sought by Fasti Online should have been explored and planned, or some other method to encourage adding new data should have been found. The website should also have been promoted heavily outside the English-speaking world; given the targeted region, reaching beyond English-language projects is critical. The language barrier does to MAGIS what selective governmental agreements do to Fasti Online: it transforms a broad-ranging project into a much smaller and less useful project. All this leads to some difficult questions. Did the authors of MAGIS plan a long-term strategy to focus on such a broad region, or did they target a large region so that they could easily find data to use? Did they have policies for data collection suitable for the large scope of their project? Given the extent of the project, had they policies for long-term development and availability so as to reach at least a critical mass of completeness? It seems not. Data is the problem.

It would be easy to pin the problems onto the lead authors, but I prefer to call for a review of funding policies and politely ask funders to integrate long-term plans in their assessments of databases accessible through the Web. The collection of data and long-term accessibility to the data are the issues at stake here. Collaboration (even enforced as a condition for funding) to avoid duplication is also required. For instance, MAGIS and Fasti Online could have been different parts a single project.

As I mentioned in the preface, websites are one of the most perishable products of research. Even when websites succeed and reach a critical mass of data and a reasonable audience, there is no security in their future if no future was planned. The results achieved by MAGIS merit praise, but its future is uncertain. This is a pity given the potential that MAGIS still shows at this advanced stage, but fulfilling that potential will require much more effort and money, and probably a change in funding policies.

-- Andrea Vianello

All articles in the CSA Newsletter are reviewed by the staff. All are published with no intention of future change(s) and are maintained at the CSA website. Changes (other than corrections of typos or similar errors) will rarely be made after publication. If any such change is made, it will be made so as to permit both the original text and the change to be determined.

Comments concerning articles are welcome, and comments, questions, concerns, and author responses will be published in separate commentary pages, as noted on the Newsletter home page.