| Vol. XXV, No. 2 | September, 2012 |

Articles in Vol. XXV, No. 2

Artifacts and Applications: Computational Thinking for Archaeologists

A new way to think about data.

-- Andrea M. Berlin

Digital Infrastructures for Archaeological Research: A European Perspective

Repositories throughout the world.

-- Julian D. Richards, Director, Archaeology Data Service, UK

Digital Data in Archaeology: The Database

Real-world examples show mixed success.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

§ Readers' comments (as of 10/22/2012)

Website Review: Mediterranean Archaeology GIS (MAGIS)

A good website waiting for more data.

-- Andrea Vianello

There Is a Difference

Digital infrastructure services are not the same as archival services.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

To comment on an article, please email

the editor using editor as the user-

name, csanet.org as the domain-name,

and the standard user@domain format.

Index of Web site and CD reviews from the Newsletter.

Limited subject index for Newsletter articles.

Direct links for articles concerning:

- the ADAP and digital archiving

- CAD modeling in archaeology and architectural history

- GIS in archaeology and architectural history

- the CSA archives

- electronic publishing

- use and design of databases

- the "CSA CAD Layer Naming Convention"

- Pompeii

- pottery profiles and capacity calculations

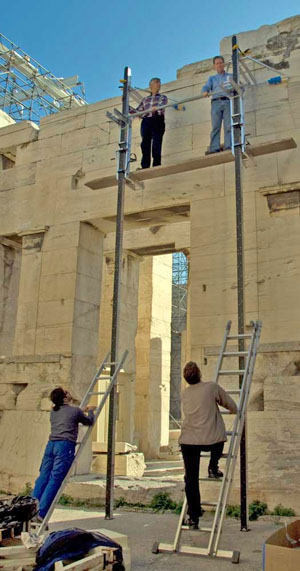

- The CSA Propylaea Project

- CSA/ADAP projects

- electronic media in the humanities

- Linux on the desktop

Search all newsletter articles.

(Using Google® advanced search

page with CSA Newsletter limit

already set.)

There Is a Difference

Harrison Eiteljorg, II

(See email contacts page for the author's email address.)

"In summary, the last 5 years has seen a number of significant initiatives to set up digital infrastructure services within a number of European countries, although those with an emphasis on preservation as well as access are so far largely confined to northern Europe." It seems to me that comment in Julian Richards' article (Richards, "Digital Infrastructures for Archaeological Research: A European Perspective," CSA Newsletter, September, 2012; XXV, 2) deserves a follow-up. Mr. Richards very carefully makes the point that there is a difference between providing "digital infrastructure services" (to provide access to archaeological information) and preserving archaeological data. These are not mutually exclusive goals, just different ones; they may be pursued together or separately. That is, it is possible to archive files without being concerned with complex access systems. It is also possible to provide complex access systems but to pay relatively little attention to the problems of preserving the original data files, as opposed to specific content. Of course, it is also possible to pursue both goals simultaneously. (A previous newsletter article — Eiteljorg, "Aggregation for Access vs. Archiving for Preservation," CSA Newsletter, September, 2010; XXIII, 2 — concerned this distinction.)

When the problems with permanence of digital data were first recognized in the early 1990s, there were various expressions of concern that data files needed to be preserved. Indeed, there was a lively debate about the best methods of such preservation, with some preferring to plan for migration of data files from their original formats to newer and newer ones over time so that the files could retain their utility as computer technology advanced (assuming that change is advancement, an equivalence with which many would take issue). Others thought it better to try to emulate the software and hardware of older computers to preserve the data within older files. Today, that argument has been brought to a quiet close. Few now argue for emulation. (Emulation still has its place when there is something particular about the use of older technology that has some impact on one's perceptions, as can be the case with digital art based upon out-dated technologies.) It is now more or less assumed that the way forward requires data migration.

At the time when data preservation was first seen as a problem, there was relatively little discussion of or concern about access. Preservation was seen as the simple goal, simple but desperately needed. Only as the quantity of digital data began to explode in the late 1990s and the early years of this century did designing complex access systems become a focus of scholars' attention. However, more and more efforts to provide reliable access to data have arisen, as Mr. Richards' article attests. Digital infrastructure services have, in fact, become more and more prominent in the discipline, while the task of data preservation (that is, digital file preservation) has, to some degree, slipped into the background as an assumed part of the access systems.

I write this to say what I have said before in various venues. I believe that archaeology as a discipline needs more repositories dedicated simply to the preservation of the data files produced by the work of scholars — whether excavating, doing field survey work, or studying material excavated years ago. Since we destroy as we dig, the evidence we generate simply must not be lost. Repositories, whether intending to provide sophisticated forms of access or not, must preserve the data files for our collective descendants. Access to data requires data.

There is another issue with data file preservation. The files from a project include a great deal more than the information about objects. There are generally files concerning excavation units (whatever they are called), groups of items found together (whatever they are called), maps, other drawings, and personnel, as well as more idiosyncratic information from every project that may have no analog elsewhere. Understanding a project requires all these files, not just the object files. But some creators of access systems see their charge as applying to the objects, not necessarily the other information. Thus, even if the information is preserved about the objects, it may be in complete isolation from the rest of the project, whether excavation or survey, and leave a user with no way to understand the processes by which the objects were found, studied, and analyzed.

In summary, then, I wish to argue here for file preservation as an important matter for our discipline. Archaeologists of the future need the entire record, not just the objects, if they are to understand fully the objects, not to mention the excavations or surveys from which they came. Therefore, I urge those providing repositories of all kinds to preserve the data files from projects as part of their mission — and to provide access to those files. Access to more discrete pieces of information, particularly information about specific objects types, via systematic digital infrastructure services is an important goal, but, while some scholarly studies may be delayed, little is lost if we must wait for such access. On the other hand, if we fail to provide long-term preservation of digital resources, much of our collective memory is lost, irretrievably lost. Unfortunately, the current situation for long-term preservation of digital data suggests that much will be lost before the necessary repositories are established.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

All articles in the CSA Newsletter are reviewed by the staff. All are published with no intention of future change(s) and are maintained at the CSA website. Changes (other than corrections of typos or similar errors) will rarely be made after publication. If any such change is made, it will be made so as to permit both the original text and the change to be determined.

Comments concerning articles are welcome, and comments, questions, concerns, and author responses will be published in separate commentary pages, as noted on the Newsletter home page.