| Vol. XXVI, No. 2 — September, 2013 |

Articles in Vol. XXVI, No. 2

Website Review: Penn Museum Interactive Research Map & Timeline

One portion of the Penn Museum website.

-- Andrea Vianello

Of Layer Names — And Babies — And Bathwater

Layer names need not be useless to be clear

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

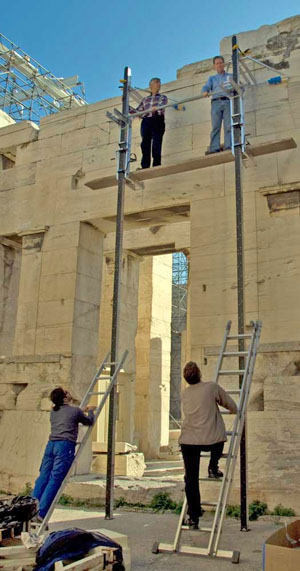

Archiving the Digital Files from the CSA Propylaea Project

Long-term preservation of the data files is necessary.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

Aggregating Data — A Very Problematic Process

Scholars often need complex and sophisitcated data.

-- Andrea Vianello and Harrison Eiteljorg, II

Miscellaneous News Items — And Some Important Questions

An irregular feature.

To comment on an article, please email

the editor using editor as the user-

name, csanet.org as the domain-name,

and the standard user@domain format.

Index of Web site and CD reviews from the Newsletter.

Limited subject index for Newsletter articles.

Direct links for articles concerning:

- the ADAP and digital archiving

- CAD modeling in archaeology and architectural history

- GIS in archaeology and architectural history

- the CSA archives

- electronic publishing

- use and design of databases

- the "CSA CAD Layer Naming Convention"

- Pompeii

- pottery profiles and capacity calculations

- The CSA Propylaea Project

- CSA/ADAP projects

- electronic media in the humanities

- Linux on the desktop

Search all newsletter articles.

(Using Google® advanced search

page with CSA Newsletter limit

already set.)

Aggregating Data — A Very Problematic Process

Andrea Vianello and Harrison Eiteljorg, II

(See email contacts page for the author's email address.)

The European Association of Archaeologists holds its conference each fall in a different city in Europe. This year's meeting was in Pilsen, the Czech Republic. Andrea Vianello and Harrison Eiteljorg, II, decided to attend both because the EAA is a group that has, for a long time, taken very seriously the issues surrounding digital data in archaeology and because there was a specific session about these issues, a session entitled "New digital developments in heritage management and research." Not only did the session seem likely to be a good one for discussion, but Mr. Vianello and Mr. Eiteljorg had presented a paper two years ago at the EAA meeting in Oslo, Norway, and thought they could usefully join forces again. So they did join forces and presented a joint paper, with Mr. Eiteljorg speaking for about 10 minutes and Mr. Vianello following for another 10 minutes. Partly because of the dynamics of the meeting, neither author read the paper he had written but extemporized in part. As a result, they are taking this opportunity to make fuller and more carefully argued statements.

The two arguments are presented here in sequence, not as a single, continuous paper. Mr. Eiteljorg's comments begin the discussion.In short, the critical question I keep returning to in many discussions about digital data and the use of such data is this: "How can we be sure that those who use large collections of digital data will understand the problems inherent in using data gathered from disparate sources in synthetic research?" That is, when data have been gathered from any number of different sources, the problems with consistent terminology and data structure will become ever more complex, and users will, I fear, be inclined to miss some of those problems as they gather the raw data upon which to build syntheses.

The standard argument about this runs something like the following. When we see the widespread commercial use of aggregated data, the results are not very problematic because the data types are simple and well-defined. We have names, street addresses, towns, countries, postal codes, telephone numbers, email addresses, and so forth. There may be problems with spelling errors, and there are some issues with formatting. (Telephone numbers in particular display formatting issues, with some people/places using parentheses to separate various parts of the total number while others use periods or only spaces.) However, operators of search engines have clearly figured out algorithms to assist with relatively simple spelling errors, often suggesting alternates to users, and the formatting issues are so easy to correct that even I can do that (although far too many web programmers who prepare data-entry forms don't seem to understand this notion).

According to this view, only more complex data types present issues of note.

Although that argument seems both logical and obvious, I have had, in my own personal experience, just the kind of problem that concerns me, but that problem lay with the most mundane of data types, the personal name. That is, after all, one of the easy kinds of computer data, the first-name, middle-name, last-name combination that more or less unambiguously denotes a single individual (ignoring for the moment the possibility of two persons sharing the same name). Despite that easy argument, I have experienced regular problems with my own name, a unique one, to say the least. My legal name — the one on my birth certificate, passport, driver's license, and other official items — is Harrison Eiteljorg, II (with no middle name). I've never worried that I would be confused with someone else of the same name. Since I have no middle name and my mother wanted a nick-name for me other than Harry, I have been known as Nick for virtually all of my life. Indeed, it is not uncommon for me to have friends come up to me at academic conferences and do a double-take upon seeing my name badge with Harrison on it. (Someone who did not know me but had seen Harrison on my name tag at a conference, once asked me if I knew Nick Eiteljorg. I have often wondered whether a more quick-witted reply, "No, tell me about him." would have been a good or bad idea.)

I learned how important this could be when using Google to check on myself before a conference for which there was some dispute about how my name would be listed in advance. I found that searches for Nick Eiteljorg or Harrison (or Harrison II) did not produce equivalent results. In fact, I found that someone searching for Harrison without the II might logically assume that I had been born in 1903 (the year of my father's birth) and was nonetheless still reasonably active; lived in Indianapolis, IN, as a businessman; and also lived in Haverford, PA, as an archaeologist. In preparing this article, in fact, I found, side-by-side on a Bing search page, a picture of myself from 2003 and one of my father from about 1990, presented as if they could be photos of the same individual. (The same two photos showed on the images page of Bing when I searched for "Harrison Eiteljorg, II," and only a small number of the images there had anything to do with me.) Tellingly, the fourth find (using Bing) for Harrison Eiteljorg, II, has nothing to do with me but concerns my father. For Google, it's the seventh item in the search for Harrison Eiteljorg, II, that is unrelated to me but about my father. For Yahoo, it's the fifth. (I also tried duckduckgo searching, and, though total numbers of hits are not shown, a reference concerning my father but not me was third on their list.) Those finds, however, did not occur when searching for "Harrison Eiteljorg, II."

This table presents the results of some searches, with different search terms for the columns and different search engines for the rows:

| Nick Eiteljorg | Harrison Eiteljorg | Harrison Eiteljorg, II | "Nick Eiteljorg" | "Harrison Eiteljorg" | "Harrison Eiteljorg, II" | |

| Bing | 6,290 finds | 29,100 | 27,100 | 2,120 | 3,980 | 5,930 |

| 55,500 | 78,100 | 149,000 | 1,530 | 8,250 | 74,200 | |

| Yahoo | no numbers supplied |

It may be worth noting that both Bing and Google managed to find more results for "Harrison Eiteljorg, II," than for "Harrison Eiteljorg." This is certainly curious, since, by any logic, the added Roman numeral should reduce the number of results, not increase it.

The point of the foregoing is simply this. Even what should be the simplest of search terms, an individual name that seems unique, is not as simple as it may seem.

But what about terms that we may use in archaeology? Do they present difficult problems, or should the problems they present be fairly simple? In Pilsen I made the point that even so reliable a source as the Beazley Archive shows fairly obvious problems. When defining amphora, for instance, there are multiple types described, but there are other types illustrated with profiles. Those shown in profile are not defined; those defined are not shown in profile. Transport amphorae are mentioned but neither described fully nor illustrated. (See this page: www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/tools/pottery/shapes/amphorae.htm, accessed 15 September 2013.)

A more problematic example might be the simple terms pin and brooch. What's the difference? Most would, I think, use the terms interchangeably, thinking only that brooch was more old-fashioned. It would be reasonable, though, to make a distinction, using pin to mean a very simple pin and brooch to mean a larger and more complex and ornate one with a pin to hold it in place. Drawing such a distinction, though, is not so simple as it may seem, since the boundary line between pin and brooch would remain difficult to define clearly.

As pointed out to me by Richard Hamilton, member of the CSA Board and retired classicist of note, in discussing the paper for the EAA meeting, any scholar should understand the terminological problems before starting out on a research project. While this is doubtless true, one wonders how such a scholar, using a database aggregated from various, disparate sources, would approach sorting out the terminological problems. In today's world, with each resource a separate book or article, such a scholar has the original author's words to use and knows the person who applied any terms to any objects. Will such knowledge be available to the user of a vast, aggregated database? At the end of the day, that is my concern. I believe that those who aggregate data have a duty to make certain that the sources of the data are clear and unambiguous — and as easily available to any researcher as the data themselves.

The concerns may be broader than would seem to be the case at first glance. Imagine trying to find all Xs in some broad geographic area that have been dated to 525-500 B.C.E. Assuming that the data aggregator has created a mechanism to provide beginning and ending dates for all Xs in the collection, how does that aggregator express the fact that one X has been dated to the last half of the sixth century B.C.E. while another was dated to 520-510 and yet another to the last quarter of the century and another perhaps to the end of the sixth or beginning of the fifth century? These distinctions may be very important to the research being conducted, or they may be quite beside the point. But the data aggregator will not know when such distinctions matter and when they do not. So they must always be preserved

I might have been persuaded that these concerns were easily over-stated and that any reasonable scholar would understand the need to deal with such problems and figure out how best to do so. However, one of the other speakers in the session in Pilsen suggested the potential value of automated searches. That made my concerns seem all too real and important. The computers of the future will doubtless be able to do many things, but I remain reluctant to think that they will be able not only to think but to understand all the distinctions that really do matter to us — without having those distinctions recorded in the data sets consulted. Therefore, I believe strongly that the data we gather into large datasets must be fully and carefully defined so that any user can determine who supplied what terms or descriptions and can, from that information, search back to find the author's definitions and other factors that impact data descriptions. We may not care that you and I pronounce potato differently, but we must care that I call a potato what you call a pomme de terre and my Hoosier father called a spud. And we certainly must know that the term does not mean Idaho potato but may indicate any one of a number of potato varieties — or not, if the data have been assembled to include only the one variety so well-known to Americans.

* * * * * * *

Mr. Vianello's comments follow here.

Let me begin with some further comments about metadata to accompany aggregated data. Nick did not use the term metadata, speaking instead about information that permits users to identify the sources of data; call it what you will — and I will call it metadata here — this is an important issue. Some careful use of metadata can go a long way in making aggregated databases more accessible; metadata ought to add some flexibility in providing information to permit a user to fit data about various artefacts into a manageable system. Metadata from thesauri and free keywords can produce links between different records that may appear different. Because of such power, however, only authors and experts should set such metadata, not those who aggregate the data. (Technical metadata that have no influence on searches or the display of records should be hidden and simply resolve technical problems.)

Since thesauri are often suggested as mechanisms to deal with metadata problems, a word about them here. At the EAA there have long been discussions about thesauri, also in connection to the use of terms in the Beazley Archive that was mentioned by Nick. I think that the use of thesauri is plainly wrong if it forces data into some categories that may not be those originally used by those compiling the data. The author must have the last word in terminology, and the reader must be presented the work of competent scholars. Constraining terminology or data in any way that makes the original scholar's views less clear is unacceptable.

Thesauri are good sources for metadata, but, in practice, scholars rarely use them to compile data. Therefore, thesauri cannot be adopted restrictively as sources of pre-made categories. The solution, which was tried and tested by Intute at the University of Oxford, is to use one or more thesauri to provide an initial list of keywords, but also to leave freedom for the author or compiler of data to use any other keyword that may seem appropriate. Hybrid or cross-cultural artefacts can best be handled this way, and peculiarities or oddities (perhaps deriving from the original description) will be included correctly. I think that it is impossible to describe material culture, or culture in the broader sense, by using one set of words only. Culture crosses boundaries and carries the complexity typical of the human brain. A good thesaurus instead imposes rigid boundaries and provides order within its specialised area, reaching reference status. Reference status does not mean that the thesaurus is comprehensive, only that within a certain field it is a sound first step. We can think of the relationship between the English language and the Oxford English Dictionary; the latter is a reference tool, but it has to catch up constantly with the language in use to maintain that status, and it never contains all words in use at a given moment. People are free to use any word not contained in the dictionary at any time, although most words used in normal speech or written work will be found in the dictionary. Similarly, thesauri will contain most words and provide basic guidance, but they will never be able to satisfy all needs. Any rigid implementation of them is methodologically faulty.

I will now turn to some slightly different issues and use Europeana as case-study (Fig. 1). Europeana is an aggregated database that may become a reference for such databases in the future. It is an ambitious project to catalogue all European culture, including art, archaeology, literature and history. At its essence, it is a database with textual records, some with pictures (especially for artefacts). There are librarians, digital specialists, scholars and members of the public expanding on it, and it is fair to say that it has been the highest-profile aggregated database in Europe since 2011. The public enthusiastically welcomed the project when it was opened online. It does not target scholars specifically, but its ambitions, the resources it has in terms of people working on it and the public funding from the European Union make it an excellent example of data aggregation that moves beyond what a single individual could do.

Fig. 1. The landing page of Europeana

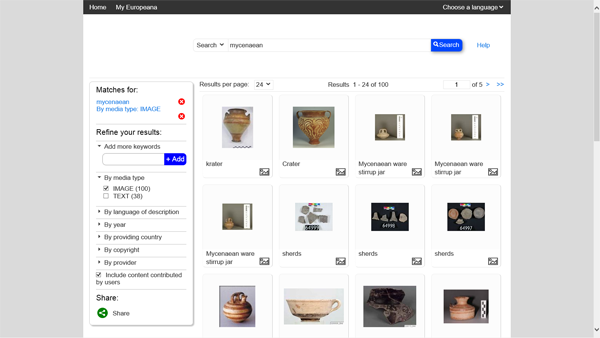

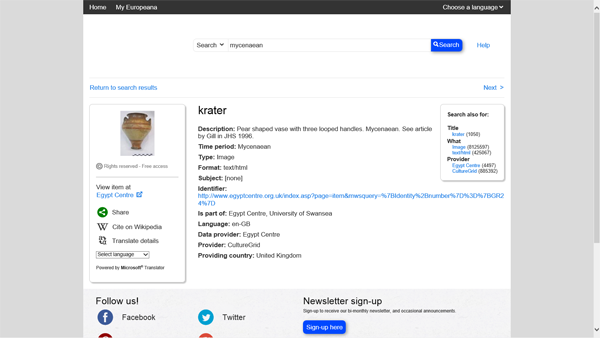

Europeana is not limited to archaeological artefacts (Fig. 2), but that will be the focus of these comments. I tried a simple keyword search for "Mycenaean" (Fig. 3), one of the major European civilisations. The database returned 100 records with images (mostly pottery) and 38 records mixed with the others about bibliographic citations, not accessible in full-text and mostly irrelevant for such a database. The quality of the pictures is also quite variable. It seems that this is a technical effort to cobble together disparate datasets in the hope that something may be useful to someone at some point. There is no direction towards a well-defined goal, and metadata are hidden. The overall quality of the records themselves is very poor (Fig. 4). Europeana's greatest success has been with the exhibitions (Fig. 5), a limited number of focussed websites-within-a-website that filled blanks in the records and required experts to review certain sections of the database; from my perspective it is a call for splitting the database into more manageable chunks.

Fig. 2. A Europeana page with artefacts.

Fig. 3. The Europeana search results for "Mycenaean."

Fig. 4. The Europeana page for a Mycenaean krater.

Fig. 5. Europeana exhibitions.

Another issue is the purpose of creating such large databases by aggregating data. I have seen plenty of enthusiastic presentations about possibilities, but very few cases where large integrated databases have been used successfully. I remember years ago that someone suggested a "definitive" database of pottery for the Mycenaean civilisation, publishing with basic measurements and at least a picture all known vessels. The idea was quickly challenged and soon abandoned. What are we going to do with such a definitive database? Would linking a few vessels chronologically or spatially separated because they appear similar in the database be a valid argument? Would such a database seal off specialist scholars from pottery that is not classed as "Mycenaean"? Would we direct research towards pure descriptive approaches and antiquarianism? Would we create silly statistics about the diffusion and presence of decorative motives and shapes when we know that the archaeological record is often a tiny fraction of the original production? Who would benefit from such a database? These are questions that are relevant to those compiling larger databases and that should be posed before attempting to produce them.

Multimedia databases pose new difficulties in the forms of proprietary files and different types of media items. I think that the original files should be made accessible but only for established, basic types of data, such as pictures, sounds, and videos. There should be some standardised preview available. In time, point-cloud data and 3D scans may become normal for monuments and artefacts. In some other cases, bibliographic data (including websites) of the original or key publication, and contextual data (about stratigraphy, the surrounding space, scientific analyses, etc.) should also form part of the record. My perspective is that we are still at the beginning of the digital revolution, at the time when we have the basic tools. But we do not yet know what to do with them. Too much work is focussed on repeating tables and catalogues that appear in printed publications. Yet too little is done to produce the ideal record. But until we know what kinds of issues archaeology wants to investigate, we cannot produce a record that can provide all the relevant information.

I think that most interested people; including students, teachers, lecturers and researchers; default to search engines for images and basic data. Perhaps scholars should produce datasets that are intended to be integrated via web searches, leaving the the search work to others while only maintaining the records. This may not be the ideal solution conceptually, but realistically it may be the best solution today to unlock the potential of culture to the masses and scholars alike. If, via search engines focusing on academic publications (e.g., Microsoft Academic Search or Google Scholar), we could have links to the records of individual artefacts and monuments published at scholarly websites, this would probably be smarter than any current database. Such a process would allow scholars to focus on individual data sets that accomplish genuine scholarly goals rather than focusing on aggregating data to try to meet a more universal, but less well-defined, goal.

In short, I advocate producing large databases slowly, by growing and linking existing databases, maintaining each database at a size that a restricted number of people (experts, professionals, scholars) can control. Public contributions can also included in separate databases. Data should be merged and aggregated into one resource only occasionally. Interfaces can be built to merge different databases and mask differences, since each set of data may contain fields that make sense only for those data. I would follow the example of the World Wide Web and treat different resources (databases) as websites, and focus on securely storing scientific data as well as producing dynamic interfaces. All giant databases will end up compromising the peculiarities of scientific and research fields and database collections, eventually going for the minimum common denominator, i.e., an unsatisfactory patchwork of resources that prefers consistency and simplicity to scientific rigour and precision. Technical staff will always press for simplicity, but having digital data as opposed to other types of data does not make them any simpler; therefore, aggregating data will not be any simpler when digital data are involved. Authors need to maintain control of their information, and users need tools that require them to locate the authors' ideas rather than a rough approximation thereof.

The two great and helpful tools that digital solutions offer are the ability to link different datasets (as opposed to citing some other work and requiring the reader to find it) and the ability to produce a virtually infinite number of interfaces to suit specific or general search-and-retrieval needs (reducing the need for works synthesising previous scholarship). I am optimistic about the future, and I recognise the usefulness of aggregating data. I am also a realist, and I can see that only a few databases have been produced, published freely and kept updated. There is still much to do at the level of the record, and the pace of new technologies will revolutionise what can be included in the record even more. Solutions such as interfaces to help with aggregating some data are already possible, but we are still a long way from producing an interface aggregating disparate data that can be as ambitious as Europeana. At the EAA it was obvious that much work is being done on creating possibilities, but we are not there yet.

-- Andrea Vianello and Harrison Eiteljorg, II

All articles in the CSA Newsletter are reviewed by the staff. All are published with no intention of future change(s) and are maintained at the CSA website. Changes (other than corrections of typos or similar errors) will rarely be made after publication. If any such change is made, it will be made so as to permit both the original text and the change to be determined.

Comments concerning articles are welcome, and comments, questions, concerns, and author responses will be published in separate commentary pages, as noted on the Newsletter home page.