| Vol. XXV, No. 3January, 2013 |

Articles in Vol. XXV, No. 3

From the sorting table to the web: The NPAP research data portal for ceramics

An extensive and inclusive database for ceramics

-- Vladimir Stissi, Jitte Waagen, and Nienke Pieters

AutoCAD® and the Resurrection of an Old Excavation

Mapping Hellenistic Gordion

-- Martin Wells

Electronic Publication — Addendum III

More in a seemingly unending series

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

The Blog in Academic Settings

A fad whose day has passed or . . . ?

-- Andrea Vianello

The Redford Conference in Archaeology

An excellent conference about digital technologies

-- Chris Mundigler

To comment on an article, please email

the editor using editor as the user-

name, csanet.org as the domain-name,

and the standard user@domain format.

Index of Web site and CD reviews from the Newsletter.

Limited subject index for Newsletter articles.

Direct links for articles concerning:

- the ADAP and digital archiving

- CAD modeling in archaeology and architectural history

- GIS in archaeology and architectural history

- the CSA archives

- electronic publishing

- use and design of databases

- the "CSA CAD Layer Naming Convention"

- Pompeii

- pottery profiles and capacity calculations

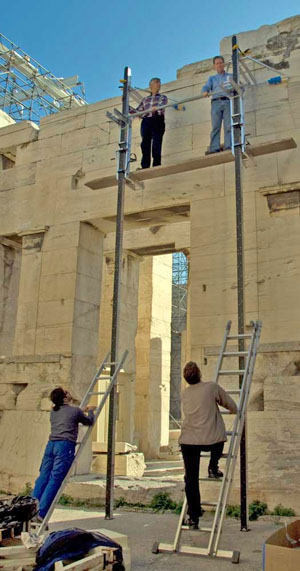

- The CSA Propylaea Project

- CSA/ADAP projects

- electronic media in the humanities

- Linux on the desktop

Search all newsletter articles.

(Using Google® advanced search

page with CSA Newsletter limit

already set.)

The Redford Conference in Archaeology

Chris Mundigler

(See email contacts page for the author's email address.)

Paradise. Different things to different people, but for the many archaeologists, technicians and students attending the recent Redford Conference in Archaeology at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington, paradise came in the form of reveling in new technologies that are redefining the field of archaeology. As one student in the audience enthusiastically proclaimed early in the conference during a Question and Answer period, “This stuff blows my mind!”

Participants for this conference came from various countries around the world and brought with them not only their theoretical expertise, but also their practical field experiences in projects that ranged from Italy, Greece, Turkey, Georgia and Israel to Peru and the Americas.

What exactly was it that so enthralled the attendees of the conference to make such proclamations? In the following article I will briefly outline the topics discussed, as well as give you some inkling as to the presentations and processes that were unveiled to the audience of archaeologists, technicians, archivists, faculty and students from around the world.

For a more detailed outline and discussion of each of the panels and presentations given at the 2012 Redford Conference in Archaeology mentioned here, please check out this author’s website.

The conference was intended to address the ways in which emerging technologies are changing, sometimes complicating and more often forcing innovation in the field of archaeology in ways scholars and researchers in the 19th and even the 20th centuries could never have imagined. The discipline of archaeology itself stretches back over the last few centuries, but it was only in the later 20th century that new technologies and innovations were given serious methodological consideration.

Now, in the 21st century, an explosion in the availability of technological tools offers the potential to transform the practice of archaeology into something never dreamt of before. But the mere existence of a new tool, no matter how exciting it might seem, does not always mean it can be put to good use in any given discipline.

Often those who study history and the past have difficulty adapting their practice to the existence of new tools, and one goal of the Redford Conference in Archaeology was to help us all learn from the experiences of others.

Some of the issues and challenges faced by the presenters and audience alike included:

- How do technological tools allow archaeologists not only to do their work differently, but better?

- What kinds of new questions do these tools allow us to ask, and why are those questions useful to a broader understanding of the ancient world?

- How is the processing of archaeological material after an excavation affected — from archiving data through to publication?

- How can we maximize the possibilities offered by the new digital technology?

Rising to this challenge, the presenters at the conference focused their discussions on three main areas to address these questions:

- Fieldwork and how traditional archaeological methods intersect with digital technologies, including the problems that technology can help us solve in the field. Just as important, perhaps, the question of how the limitations of these technologies can hinder archaeology or, at the very least, not help us in our fieldwork.

- Given archiving and the fact that technology increases the amount of information we gain from the field, this information must be stored properly so that it can be efficiently accessed again in the future. The question of how we can account for future changes in technology that might make current storage techniques obsolete was an important aspect of this topic. Other important questions included avoiding the loss of data when that happens and mitigating any problems that technological change may present.

- Publication and the possibilities that are opened up for us by digital technology. Making these new electronic publications more valuable and increasing the quality, not just the quantity, of the published material was another important consideration. And this brought up the question of whether or not peer review will still be an important process connected to the new electronic publication possibilities.

The conference began with a public lecture, scheduled before the actual opening of the conference, "Showing the Invisible: 3-D Scanning in the Roman Catacombs" by Dr. Norbert Zimmermann of the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna. Dr. Zimmermann offered his audience the opportunity to take a “mind-blowing” (as that student put it so eloquently) virtual tour of the catacombs of Domitilla in Rome (see this page www.learn.columbia.edu/treasuresofheaven/shrines/Rome/video/index.php for a sample of the visualization presented), and he discussed how archaeology can best use the new high-tech hardware and software scanning capabilities available today.

The conference proper began the next day with an overarching "Taking Archaeology Digital" address by this author to introduce the audience to the many and varied aspects of the new technologies available to archaeology, from hardware possibilities (such as touch-screen computers and tablets), to survey and photographic equipment (including remote helicopters), to the amazing variety of publicly-available and specialized software (both commercial and Open Source) for data collection, analysis and presentation, to cloud-based applications in GIS, CAD, imaging, and much more.

From there, the conference got into full-swing with presentations, demonstrations and critical discussions on the three main themes mentioned earlier.

The first panel of the conference addressed the issues of going paperless in recording and managing data in the field at projects in Italy, Georgia and Peru. Data entry systems and workflows (mostly for tablet technology) tended to come to the same conclusion: the all-important aspect of an efficient Graphical User Interface (or GUI). The aim in putting together these field systems was to decrease the amount of work, increase the accuracy and make the data seamlessly available in Geographic Information Systems (GIS), computer-assisted drafting (CAD) and database formats as soon as possible after, or even during, the fieldwork itself. For the projects presented, these goals were met with varying degrees of success (and occasional failure). One system that did work very efficiently for various projects and was a great time-saver, as well as being more accurate than stone-by-stone (SBS) drawing, was photogrammetry, also used by this author on a number of projects in Greece, Italy and Jordan with great success. New and improved 3D software has made the photogrammetric process easy and quick with minimal training (the latter being another concern expressed at the conference).

This was followed by a commentary from Sebastian Heath of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at NYU, "When Worlds Link: the Context of Digital Archaeology," in which it was emphasized that the original context of an artifact must be maintained throughout the "chain of custody" from field to lab to internet, at which point distribution and licensing considerations come into play.

After a brief lunch, the conference resumed with a presentation on the Archeolink information system software developed in Europe to meet the data management needs of any archaeological project — easier data entry, fewer errors, better data management and sharing, and just as important, standardization of the archaeological data.

Harrison (Nick) Eiteljorg, II, (Director of the Center for the Study of Architecture, and editor of the CSA Newsletter) picked up the pace again after lunch with "The State of Digital Publication" and archiving, not to mention all the challenges that await archaeologists in terms of data archiving, its usefulness and open access into the future.

Following this, a panel on Digital Publication presented various aspects of transitioning old data to the new digital formats, as well as some of the advantages of using Open Access publication (or virtually unrestricted access to peer-reviewed journals and research via the internet) versus more traditional print publication — while still maintaining the integrity, credibility and reputation of both the material and the authors. One of the main issues here is that, to date, there really is no standard of publication or best-practice set within archaeology, and if 2D and 3D material is to be published on the internet (preferably Open Access), standards and formats will need to be looked at closely in terms of storage and searchability. Time and cost benefits weigh heavily in favor of "born-digital" publication, and now it’s just a matter of getting archaeologists and publication houses to communicate, standardize and get the job done.

Next, the panel on Uses of GIS within archaeology brought the audience face-to-face with the many ways in which survey mapping on field projects is challenged with accurately representing datasets in spatial locations and how best to access that data in meaningful ways. As with digital publication, GIS data must be stored in such a way that it will be accessible for generations to come, as well as available for the widest use and analysis possible of that data.

The final segment of the conference was a panel on Imaging Technology, which presented ways in which 3D laser and optical scanners can be used to capture archaeological information in the most expedient and accurate ways possible. Here again, one of the main issues was keeping the data viable well into the future; so consideration of the format, standardization and quality of the data captured is paramount.

Concluding remarks by Nick Eiteljorg summarized the fascinating topics discussed at the conference, reminded us that change is here to stay, and left the audience pondering and wondering what a carefully and cautiously embraced future in archaeology may hold for us all.

As a side note, it was very interesting to note the largely younger audience in attendance at the conference and the many implications that all of this new and exciting technology will have on the way they do archaeology in the future. While computer gaming technology that is now being used in archaeological representations is something quite foreign and astonishing for past generations of archaeologists, it’s something that is taken quite in stride by the new generation of Blegens, Carters and Schliemanns. We’re now able to view real-world archaeology as virtual 3D models and at the same time do things and see things that are just not possible in our real world — just as with a video game, only with our own ancestors as players on a digital stage. It all becomes very cost- and time-effective in a win-win scenario of bringing the past to life from anywhere in the world and taking archaeology digital in ways never before considered.

As is no doubt apparent by this all-too-brief synopsis (and the accompanying website) of the 2012 Redford Conference in Archaeology at the University of Puget Sound, archaeology is headed in new and exciting directions. It’s not just the next generations of archaeologists, scholars and researchers that will benefit from these innovations; those working in the field today and tomorrow will benefit just as much from this new technology and the speed at which it’s changing archaeology (and changing us).

-- Chris Mundigler

All articles in the CSA Newsletter are reviewed by the staff. All are published with no intention of future change(s) and are maintained at the CSA website. Changes (other than corrections of typos or similar errors) will rarely be made after publication. If any such change is made, it will be made so as to permit both the original text and the change to be determined.

Comments concerning articles are welcome, and comments, questions, concerns, and author responses will be published in separate commentary pages, as noted on the Newsletter home page.