| Vol. XXIV, No. 1 | April, 2011 |

Articles in Vol. XXIV, No. 1

Project Publication on the Web — II

What are the motivating factors?

-- Andrea Vianello, Intute and Harrison Eiteljorg, II

Website Review: Archaeological Institute of America

The AIA's redesigned website.

-- Phoebe A. Sheftel

Website Review: Kerma

An archaeological project from Africa on the web.

-- Andrea Vianello, Intute

Calibration or Ground-Truthing Is Critical

Confidence in analyses requires confidence in the base data.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

Let Us Set the Mental Juices Flowing

Artifacts should tell a story, not be the story.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

To comment on an article, please email

the editor using editor as the user-

name, csanet.org as the domain-name,

and the standard user@domain format.

Index of Web site and CD reviews from the Newsletter.

Limited subject index for Newsletter articles.

Direct links for articles concerning:

- the ADAP and digital archiving

- CAD modeling in archaeology and architectural history

- GIS in archaeology and architectural history

- the CSA archives

- electronic publishing

- use and design of databases

- the "CSA CAD Layer Naming Convention"

- Pompeii

- pottery profiles and capacity calculations

- The CSA Propylaea Project

- CSA/ADAP projects

- electronic media in the humanities

- Linux on the desktop

Project Publication on the Web — II

Andrea Vianello, Intute and Harrison Eiteljorg, II

(See email contacts page for the author's email address.)

In the first article in this series - "Project Publication on the Web — I," the authors took it as a given that publishing archaeological projects on the web is a good idea. We then discussed the early decisions that must be made before heading down the electronic publication road. We focused a good deal of attention on the basic question of whether or not publishing archaeological project data via a website should be undertaken for a given project with a given group of investigators. In this second article in the series we will be speaking to those who have decided that it is possible to go forward with the creation of a website to publish project results, and we assume that the questions in the first article have been fully explored.

Since we assumed that a website is a good venue for publication in that first article, we did not tackle the basic question of intent. That is, we assumed a desire to publish project results on the web and discussed roadblocks but not needs, not the driving motivations for putting material on the web in the first instance. So we begin here with that issue: basic motivation - not simply because this is important (most people will have their own motives if they have even considered the question) but because the motivations will vary from project to project and will impact many choices of processes and procedures.

Here is a simple list of the needs to publish on the web that we see as potentially primary for one or another project. They will provide the starting points for this discussion.

- The need to make data available to other scholars — complete and in their original, digital forms.

- The need to present results quickly and inexpensively.

- The need to present results to multiple audiences, both professional and not, for the widest possible dissemination.

- The need to include digital files (e.g., video or color photos) in the final publication.

- The need to link to other digital sources (e.g. GIS maps) in the final publication.

- The need to foster communication between/among project participants between field seasons.

- The desire to get involvement and participation from other scholars.

- The desire to bring some of the excitement of the project and even archaeology in general to various audiences beyond the scholarly.

Once again, we have as many questions as answers, because we believe that asking the right questions can be the most important task.

1. For many scholars the most important single motivation for having a website is the desire to make the raw data available to colleagues. Indeed, most would take the need to make the actual data available to other scholars as a requirement, not a choice. After all, archaeology is necessarily destructive, making the information the critical result of a process that cannot be repeated and therefore placing an ethical imperative on sharing that information. A second factor is the understanding that all the data should be available to colleagues, not just summaries or analyses. A good example of the presentation of basic information may be the pottery catalog from Kommos, as noted in Mr. Vianello's review of the Kommos website: "Website Review: Kommos Excavation, Crete," by Andrea Vianello, CSA Newsletter XXIII, 2; September, 2010.

To the extent that data have been collected and stored in a digital format, they can only be effectively shared in that digital format. Therefore, making the data available to other scholars requires making the digital files available to those other scholars or providing direct access to information over the web, as was done for Kommos in the example cited above.

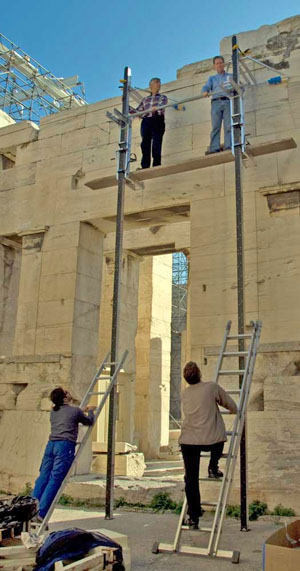

Even when the project itself is not destructive, as in the CSA Propylaea Project, presenting the data in digital form may be required. Indeed, when Mr. Eiteljorg composed the original grant request for the CSA Propylaea Project, presenting all the data on the web was a key component. The intended CAD model, of course, required a digital approach, but so did the attempt to share with other scholars basic information about the survey practices, the actual survey data, information about photographs, and the photographs themselves.

A website, however, is not the only way to make raw data available. Archival repositories such as the Archaeology Data Service in Britain and the new Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR) in the U.S. are also available to accomplish that end, and, in fact, they may be preferable since they are more likely to maintain data in perpetuity. Therefore, if the presentation of the data is a prime motivation, it is important that the project team either utilize an archival repository (alone or in addition to a project website) or obtain some form of guaranteed permanence for the project's website from those responsible for the site after the departure of the project director(s).

Archival repositories may seem to be preferable to a project website for long-term data storage, but there are reasons to prefer putting the data up on a project website rather than — or in addition to — an archival website. On a project website, the data can be formatted, presented, and described in ways that are more in keeping with the goals, methods, and procedures of the project. In an archival repository, on the other hand, the data will likely be presented as a small part of a much larger, more inclusive corpus.

In addition, a project website can and presumably will present the data in the forms chosen by the project as part of their digital planning — as complete files, presumably with relational connections for tabular data. An archival website will most likely re-format the data into forms preferred by the archives so as to make the data throughout the archives more uniform. This can result in a real and serious loss of information. In addition, not all archival repositories are prepared to accept CAD and GIS files. Thus, for many projects it will be necessary to consider preserving data on a project website, even if an archival repository is also to be used.

Despite the foregoing concerns about archival repositories, many scholars would be satisfied with having files in an archival repository rather than on a project website. The authors would not contest that choice in all instances, but we would strongly caution project directors to be certain that archival repositories will accept, share, and curate all the data from the project, not just selected portions. In addition, the archival repository should, in our opinions, maintain the project's files for access in perpetuity — and in their original formats — even if the data contained in those files have been extracted for inclusion in other, more inclusive files in that repository. In our judgment, a scholar wishing to restudy the material from a project must have access to the original files, as they were created in the course of the work, not just the data from those files. (We acknowledge that data migration may make it impossible to maintain the actual files created by the project over a lengthy period. Nevertheless, migrated files will maintain not only important data but critical indications of the processes and procedures used in the project.)

2. Speed of publication is certainly another reason to choose the web as a primary mechanism for presenting project results. When co-author Eiteljorg was working on the book that became Archaeological Computing, one of the reasons he decided to publish the finished product online (in PDF form) was the possibility of getting the book out before it had become obsolete. The two-year delay he anticipated for paper publication would have made that much harder. Data from an archaeological project will certainly not become obsolete if its publication is delayed, but the timeliness of the publication will inevitably be impacted by the processes required for paper publication. On the other hand, it is important to recognize that good publication — whether on paper or on the web — requires full and careful editing. As a result, the difference in speed of publication may be less significant than might seem to be the case.

Interim reports of a project's progress, if issued, would not require peer review, and speed of access by interested scholars would be greatly enhanced if such reports were placed on a website. In addition to the speed advantage, these reports would almost certainly be more widely available than the closest current analogs, conference papers.

The International Dunhuang Project provides an excellent example of speedy production of materials on the web. Indeed, this project is putting material up, ready for searching, without waiting for all to be ready. To be sure, the materials are appearing online in sensible groups, not one-at-a-time, but the point is that speed is an issue, and the web's utility in this area is being utilized. (See "Web Site Review: The International Dunhuang Project," by Susan C. Jones, CSA Newsletter, XXI, 2; September, 2008.)

Speed of publication will also be impacted by the review process. If there is to be an attempt to obtain peer review for those publications on the web that most nearly mimic traditional paper publications, that peer-review process will surely slow the publication on the web just as it slows paper publications. Nevertheless, the time required for actual printing entails additional delays, not the least of which is the time spent proofreading intermediate stages of the printed product.

Affordability is also an issue. It has become virtually axiomatic that paper publications of large-scale archaeological projects result in very costly products, books that too often can be purchased only by libraries. On the web, of course, everything is "free." The problem is that the project cannot recoup the costs of its website. On the other hand, at least some of the costs of publication are covered by sales of the resulting books.

If affordability is one of the primary motivations for developing a website, it is critical that the project directors succeed in raising funds to ensure the production of a good website as part of the project funding base. It is therefore incumbent upon the project directors to make the argument that access needs to be affordable and to convince funding agencies and/or foundations to sign onto that notion.

3. A website offers the possibility of presenting the material in many different ways in one place and under one set of directors. While it is not impossible, by any means, to reach different audiences with paper publications — some, for example, in academic journals with others in general-audience publications — using the website to reach multiple audiences offers significant advantages. For example, professionals whose primary fields of interest are not involved, may want a combination of materials intended for scholars and materials intended for a more general audience. Similarly, interested non-professionals may also want access to both general-audience materials and professional materials. In addition, the pages created for the website — all of them, no matter the audience — will all be able to utilize any of the data files stored on the site. Thus, for example, photographs may be used many times in many different places, and the same would be true for video, drawings, and any other digital data.

4. As archaeological projects become more and more attuned to the new digital world, more and more of them will be storing an ever greater quantity of information about their discoveries in one or another digital format, not to mention using digital files of other kinds, e.g., audio or video files. As a result, sharing the information with scholars or the wider public often requires sharing digital files. Doing that via paper publications is all but impossible. To be sure, a CD or DVD can be packaged in a paper publication, but that approach, which may have seemed state-of-the-art a decade ago would seem absurdly retrograde today because the files on the CD or DVD might last only a rather short time (from a few years to a decade or so), whereas files on a website can be kept current. This is a very strong argument for the use of a website as a publication forum. (The Dunhuang site is a good example again, as the use of images in the database is a very important asset for the site - and its users.)

5. As digital files are often desirable, in truth crucial today, so being able to link to external digital data is also becoming more and more necessary. GIS files provide the most compelling example today. When GIS files are used, it is very common for scholars to use available files created by others as part(s) of their base. (This seems to be the case with the GIS portion of the TAY — Archaeological Settlements of Turkey — project website.) A project requiring such files might easily link to them rather than requiring that the files be duplicated on the project website. Of course, whether using linked files or duplicating them, no project using such files could adequately publish on paper. Using GIS effectively requires online publication or online availability via the chosen archives.

6. It is often very difficult for project participants to work on the materials from the project during the time between seasons when many other demands on their time keep them occupied. A website, however, can provide a locus for blogs, discussions lists, video conferencing or other mechanisms to permit project participants to discuss problems and analytic issues during the academic year. To be sure, any two participants can easily enough talk on the telephone, email, or even chat with a video connection, all without a website. A website, though, provides a valuable locus for such virtual meetings, especially when they might involve more than two people. A website may also provide ways for the fruits of such meetings to be more widely shared. For example, see "The Official and Unofficial Weblog of the Tell es-Safi/Gath Archaeological Project - a Review," by Jack Cheng, CSA Newsletter, XIX, 1; Spring, 2006.

7. No project has a monopoly on scholars who can contribute to the dialogue that is a part of the analytic process as the disparate pieces of the project are being fitted together. Therefore, it can be extremely valuable to provide mechanisms similar to those used by project participants so that scholars from outside the project can also contribute. Whatever the mechanism, a website can be the critical element in making this happen — and enlarging the group involved in the analytic processes. (The Telles-Safi/Gath blog fits that model, including both project participants and others. Similarly, Marina De Franceschini's review of the Ostia website, "Web Site Review: Ostia. Harbor city of ancient Rome, " CSA Newsletter, XIX, 3; Winter, 2007 points out the potential to "Join the mailing list: Here you can read how to join the Internet Group Ostia mailing list, which is meant for scientists and lay-people." (Last accessed 3/25/11)

8. A project website can provide a multitude of ways to permit and encourage people — project participants, other scholars, or the broader public — to learn about the work of the project — and possibly to move into the smaller group of people more actively participating. Indeed, the best sites seem to be deigned to take people from the most general kinds of information to very detailed, specific data, allowing the individual to determine when and where to stop or continue learning. Of those reviewed for the CSA Newsletter, Ostia's website may show the most range, from introductory materials to graffiti to full texts of books and articles to the discussion list already mentioned.

As the Ostia website shows, it is possible to use a website to present information in ways that would encourage various readers to learn more about the project — and to see its importance — ranging from simple photographs with good captions to videos of work processes to virtual museums on the web. Each of these approaches offers the potential to attract other scholars and/or the general public and therefore to spread the word beyond the project workforce long before final publications could be produced.

Having discussed the reasons to choose to build a website and, in the previous article, the impediments to that choice, we turn now to the most basic and important issue to be faced if a website is to be used as a project's publication venue. Who will be in charge on the digital side of things and what exactly will the job be? The reason this is such an important matter should be obvious. The scholars in charge of the project simply cannot be the ones in charge of the digital structure of the project's underlying data systems. They will — in part by answering the questions posed here — have defined the core elements of the site, but they will not have the skills or experience to build the site. Thus, the first issue is to define the job of digital director in order to prepare a job description and find the right person. We carefully did not choose the term "web master" because we do not believe that the project is well-served by thinking of the position as a web master's position. Rather, we would suggest that the job title should be something akin to Digital Information Officer. The title is not important. The scope of duties, on the other hand, is not simply important; it is critical.

We believe that there must be a project staff member whose responsibilities include all matters digital — the hardware and software chosen, the file formats accepted (even for photographs), the procedures followed, and so on. This person must be a part of the team from the very beginning because so many of the digital decisions have wide ramifications, and he/she must be chosen with great care. The responsibilities include not only the computing equipment and programs but many work processes. For instance, a choice to use iPads in the field (as illustrated at http://buzzintechnology.com/2010/09/apple-ipad-helped-scientists-dig-deep-at-ancient-pompeii/) is as much about process as it is about equipment. It assumes that much of the work will be done in the excavation trench, not in the workrooms after the day's digging is finished. Similarly, the ways photographs are chosen for inclusion in the project database will require explicit rules to avoid massive numbers of photographs being included as various members of the project team take repetitive photographs for their own purposes.

The foregoing should not be taken to imply that the Digital Information Officer will make the choices on his/her own. Rather, that person should be the one who assembles information and drives the decision-making processes when it comes to matters digital.

One part of the selection process must be the ability of the Digital Information Officer to keep careful records of the work he/she does from the very beginning. It is very unlikely that this person will stay in the job for the duration of the project; the better the person is, the more likely it is that he/she will move on to another job before the project has been completed. Therefore, record-keeping about the choices considered, the decisions made, the understood compromises, and so on are absolutely critical. Eventually someone else will be taking over the position and in need of those notes.

From the time when the Digital Information Officer comes onto the team forward, the decisions should be made by the scholarly director(s) with the Digital Information Officer. Indeed, the chief geek (we just could not manage calling this person the DIO) should be as involved in as wide a range of decisions as possible. Virtually every decision will have some impact on matters digital — if only how many files must be available for access.

Indeed, three of the questions already discussed — the possible need for an external archival repository, access to individual data items, and the nature of the audience(s) — should not be determined until the chief geek is on the team. His/her input on these matters — all of which have a large bearing on the complexity of the job — will be very important.

Given the complexity of this process of using the web as a site publication locus, we choose to stop this article here. In the next article we will continue to examine rather basic choices that will inform the day-to-day work of the project.

-- Andrea Vianello and Harrison Eiteljorg, II

For the next article in this series, please see "Project Publication on the Web — III" at csanet.org/newsletter/fall11/nlf1101.html.

All articles in the CSA Newsletter are reviewed by the staff. All are published with no intention of future change(s) and are maintained at the CSA website. Changes (other than corrections of typos or similar errors) will rarely be made after publication. If any such change is made, it will be made so as to permit both the original text and the change to be determined.

Comments concerning articles are welcome, and comments, questions, concerns, and author responses will be published in separate commentary pages, as noted on the Newsletter home page.