| Vol. XXIII, No. 3 | January, 2011 |

Articles in Vol. XXIII, No. 3

Bridging the Communication Gap: Should academics go public with what they know?

Speaking beyond the walls of academe.

-- Peter A. Young

Project Publication on the Web — I

The first questions are easy to ask, harder to answer.

-- Andrea Vianello, Intute and Harrison Eiteljorg, II

Website Review: Petras Excavations

An archaeological project published on the web.

-- Andrea Vianello, Intute

Aegeanet

A short history of the long-running listserv.

-- John G. Younger

A Review: AutoCAD® for the MAC 2011

More like an upgrade than a new version.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

The Skies Are Clouding Up Even More

Keep your data where you can find them.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

To comment on an article, please email

the editor using editor as the user-

name, csanet.org as the domain-name,

and the standard user@domain format.

Index of Web site and CD reviews from the Newsletter.

Limited subject index for Newsletter articles.

Direct links for articles concerning:

- the ADAP and digital archiving

- CAD modeling in archaeology and architectural history

- GIS in archaeology and architectural history

- the CSA archives

- electronic publishing

- use and design of databases

- the "CSA CAD Layer Naming Convention"

- Pompeii

- pottery profiles and capacity calculations

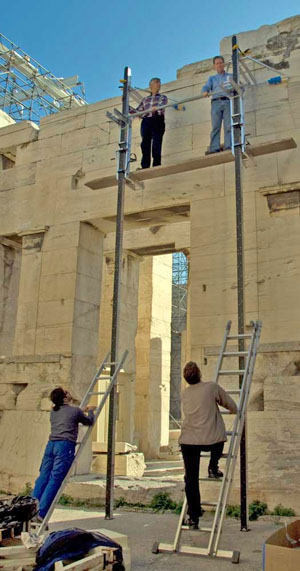

- The CSA Propylaea Project

- CSA/ADAP projects

- electronic media in the humanities

- Linux on the desktop

Project Publication on the Web — I

Andrea Vianello, Intute and Harrison Eiteljorg, II

(See email contacts page for the author's email address.)

Andrea Vianello and Nick Eiteljorg indicated at the time of the publication of the last issue of the CSA Newsletter that they would undertake a discussion of the use of web sites to present the data from an archaeological project. A web page was set up to suggest areas of interest (at http://csanet.org/newsletter/webpub.html), and colleagues were asked individually to make suggestions. Many of those responses were remarkably helpful, and we appreciate the time and effort offered by those who gave us the benefit of their thoughts. They certainly helped us to expand our views and the range of our considerations.

As time passed and we read the comments from colleagues, it became apparent that the first and most important questions are not ones for which we can provide answers. In fact, as someone once said, sometimes the question is the answer — in the sense that knowing the right questions to ask can be more important that pretending that there are clear and certain answers. As a result, much of what we will be saying has to do with finding the right questions at the right time in a project. While we will offer some ideas and comments about how to answer those questions, it is the need to face them and find your own answers that is most urgently required.

We also found that the areas of concern are so numerous that we cannot reasonably cover all, or even a majority, in a single article. As a result, this is the first article in what will now be a series concerning the use of web sites to publish the results of archaeological projects.

To define the issues more carefully, let us specify at the outset that we use the vague, general term archaeological project intentionally so that it may include an excavation, a survey, or any other field work. To the extent that such a broad definition creates problems or secondary questions, we will attempt to deal with those as they arise.

We need also to be clear that we are interested in the use of web sites to present both data and text but that we do not mean to suggest that any such web site must be the sole method of presentation. Standard paper publications may well be part of the mix, and we will try to be clear and explicit about the complications introduced by hybrid approaches.

We begin here with the important point that the decision about web-based "publication" (in quotation marks to make it clear that we mean something that may be very much like or very different from paper publication) is one that must be made early in the life of a project. This is true if for no other reason than the need to include publication costs in a grant proposal. It is also important to decide the issue early because much of the organization of a project will be affected by a determination to use the web as the publication medium.

That being said, the first and most basic set of questions that any scholar must ask himself/herself before beginning a project with a web site as a primary medium for the results of the work is this:

1. Is publication of this material needed for tenure or advancement? If so, will the home institution evaluate an electronic publication (again in the most generic sense possible) as equivalent to a paper one?

This first set of questions is the one advocates of electronic publication hate to hear — because the answer to the second individual question is so rarely positive. Few institutions will treat an electronic publication as equal in value to a paper publication. As a result, it is virtually a given that, if the publication of project results is to be used to obtain advancement in an academic position, publication should be on paper.

We do not mean here to be totally pessimistic, only to be realistic. Individual settings will be different, but each scholar must evaluate his/her situation, institution, and collegial setting realistically in order to decide on a course of action. In doing so, nobody should pretend that this question is immaterial; nor should the answer be based on presumptions that like-minded colleagues will truly be like-minded when tenure or advancement is determined. Serious discussions with the proverbial powers that be should be part of the decision-making process.

It is important to say again that these discussions should not await the launching of a project. The decision to publish electronically should have been made before starting the project; so scholars should examine this issue long before the need to post materials on the web has arisen. Sadly, this means that a scholar may be obliged to set out today on a course of action that, when the time comes, could be different. That is, if one must decide to publish via a web site today based upon possible credit for academic advancement, the decision may well be based on 2011 views of technology that might have changed completely by the time anything of note actually appears — on paper or on the web.

The need for publication credit may drive a scholar to reject the web site as all-inclusive locus for text and data and settle instead on a hybrid approach, with some paper publications and some web-based publication. If so, what will be placed on the web and what on paper? Will the paper publications eventually be placed on the web as well? (This may entail discussions with publishers and may or may not be acceptable to them.) It may be necessary to publish substantial portions of the results on paper in order to gain tenure or advancement, and the use of the web may, of necessity, be limited to those materials that do not naturally lend themselves to paper presentation: most photographs (virtually all color ones), data files, GIS data sets, CAD models.

It may be that paper publications will ultimately be placed on the site once the author/authors has/have reaped the critical benefit. It may also be that only one or two of the volumes that might result from the project will be paper publications and that everything else will be on the web. These choices need not be made irrevocably at the outset, but they will impact costs.

The other early questions now follow.

2. Do funders accept digital publication as adequate?

This question, of course, will be determined by the funders, not the principle investigator(s), and the answer may not be the same for all funders approached. Most potential funders will probably be more than willing to discuss the issue in advance, but ultimately the proposal must be explicit as to the publication plans and the nature of those publications. Assuming that the needs for scholarly advancement can be met by electronic means, this is the second major hurdle; we believe that, properly conceived and presented, the use of the web as a publication medium will be well-received by most funders.

3. What are the real costs of electronic publication, and can the project bear those costs?

Of course, the costs must be fully estimated before a proposal is written because the publication costs should be part of the overall budget. However, such determinations of publication costs must be realistic — and compared to realistic paper publication costs. A web site that is intended to contain project data alone will need regular maintenance for some years after the completion of the project at the least, because data will need to be updated, refined, and corrected over some length of time. Furthermore, web standards and capabilities will change over time, making it necessary to keep staff available for maintaining the web site for some years. If the project must employ and pay all costs for personnel to build and maintain a web site, this may be prohibitive. If, on the other hand, personnel employed by the home institution can work on the project part-time, costs should be more reasonable. In either case, it would be unwise to assume that the archaeologists will be able to build and maintain a web site without outside expertise. That may be possible, but it would likely mean that insufficient time would remain for another project or for teaching or for research.

If the full publication of all materials — analytic texts, descriptive texts, photographs, and data — is the aim, then even longer-term maintenance of the web site becomes an issue. Starting down this all-inclusive path would seem to require that revisions, additions, corrections, and the like be a standard feature of the site. As a result, on-going changes will be natural, and regular updates should be expected. Such updates may be frequent (daily updates during excavations or possibly even a blog), seasonal (preliminary report at the end of each field campaign), infrequent (final reports only for each component of the project as it becomes available), or mixed (some parts updated frequently, others not). Any combination of the preceding will impact both the character of the website and the costs of running it.

In addition, there will be more difficulties with a web site intended to hold all materials because of the need to maintain multiple versions of documents that may take years to reach a final stage. (Any document published on the Web should not be modified directly; rather it should be updated with clearly separated and dated additions, and with carefully-designed, two-way links between versions.) Doing that is not only complex; doing it well — so that users know without doubt what materials are still likely to change, where a given document sits in the sequence from first to latest, who has made what changes, and so on — is essential.

No matter the plan for long-term maintenance of the web site, the funding must be realistically estimated. It cannot be absolutely correct, any more than any other aspect of a long-term project can be accurately predicted in advance. However, it must not be based upon pie-in-the-sky estimates and projections.

4. Will the web site be the ultimate repository of the underlying data from the project? It seems natural to assume that to be the case, but letting the web site be the final repository requires taking on a very large additional responsibility. Archival preservation of digital records remains technically demanding and time-consuming work. It also assumes that there will be people available to maintain the materials long after the authors and principle investigators have ceased to be in charge. Thus, it may be preferable to make arrangements with an archival repository to take responsibility for the records in due course. If so, those plans must also be made very early in the history of the project to prevent duplication of labor and to be sure that the files to be preserved are in the correct formats. This is a more important issue than may be supposed since many file formats used in the course of a project may be superior for the project but not for long-term preservation and access.

5. Archival repositories are often interested in providing access to individual items of information from their files over the web, e.g., using a standard query mechanism to obtain a listing of chipped-stone tools of a given shape from a project. Should the web site for a project provide that kind of low-level access to the data? If so, there are substantial additional technical requirements for the ways data are stored on the site, and those must be well-planned in advance. Of course, such data access will also impact costs.

6. What will the audience of the web site be? Will that choice be consistent? To begin with the second question, it seems obvious that a project web site will have many aims over its life, including simple, practical needs while the project is on-going (e.g., information about volunteering, traveling to the site, or contacting principle investigators) and short-term information about the work as it goes forward (e.g., project newsletters). Over time, however, some of those uses of the site will fade away. When that happens, when the project itself is complete, who will be the audience? If the site is intended only for scholars, the needs are very different than they would be if the general public were also considered. Thus, defining the audience of a website early is critical to maintaining consistent quality throughout the production of the website and to prioritizing different parts. Grant applications may speak to these issues, and the choices must be clear to all involved. An intention to reach beyond interested scholars might even require hiring authors or editors specifically equipped to reach out to the general public.

As Peter Young has pointed out in "Bridging the Communication Gap: Should academics go public with what they know?" in this issue of the CSA Newsletter, it is important, for a variety of reasons, to speak to the public about archaeological work. We agree with him that a section of the website should be intended for the general public and at least one simple page outlining the project and its cultural/social importance in layman's terms should be present; press releases may also appear on the site — written in a proper format for use by journalists. It is important that the materials aimed at a more general audience not only be written for that audience but be identifiable so that any user of the site can be sure what the aims and readership of a given web page are meant to be.

Presenting research projects to the public in an appropriate manner will become increasingly important, and many lessons may be learned from early initiatives such as You Cut, a blatantly political and ill-informed attack on spending at the National Science Foundation (with a strong reaction at http://blogs.nature.com/news/thegreatbeyond/2010/12/ you_cut_misfires_with_attack_o.html). This attempt to tar specific NSF grants makes it clear just how important it is to keep the public informed about the real work done on archaeological projects. Materials aimed at the general public should not be a "watered down" version of the academic materials, but original and independent work explaining the project to non-specialists (including academics of other disciplines).

All the questions posed above are the relatively easy ones to bring to mind. But they are the ones that must be asked well in advance so that the actual work, when it comes, is properly defined. These are not the technical questions; nor are they personnel questions. However, honest answers will require consulting with people who know both the technical and the personnel problems well enough to help with planning the budget. Indeed, if the determination is made to move forward with a web site as the project's publication locus, one of the most important early decisions will be finding and bringing onto the project team someone with the necessary technical background to carry out the project aims. That person should not be casually or lightly chosen, and his/her involvement should begin well before the field work. With that technical person in place (not necessarily as a full-time employee, to be sure), the nature of the digital portion of the project can be carefully planned, and the decisions to be discussed in the next articles in this series can be effectively approached.

-- Andrea Vianello and Harrison Eiteljorg, II

For the next article in this series, please see "Project Publication on the Web — II" at csanet.org/newsletter/spring11/nls1101.html.

All articles in the CSA Newsletter are reviewed by the staff. All are published with no intention of future change(s) and are maintained at the CSA website. Changes (other than corrections of typos or similar errors) will rarely be made after publication. If any such change is made, it will be made so as to permit both the original text and the change to be determined.

Comments concerning articles are welcome, and comments, questions, concerns, and author responses will be published in separate commentary pages, as noted on the Newsletter home page.