| Vol. XXVI, No. 1April, 2013 |

Articles in Vol. XXVI, No. 1

Digital Data — Ur of the Chaldees: A Virtual Vision of Woolley's Excavations

Preserving data from a very old excavation

-- William B. Hafford

Rethinking CAD Structures — Pompeii Archaeological Research Project: Porta Stabia

Making AutoCAD easier to use effectively

-- Gregory Tucker, University of Michigan, and John Wallrodt, University of Cincinnati

Website Review: Penn Museum

An enormous website with more pluses than minuses.

-- Andrea Vianello

How Often Must We Reinvent the Wheel?

Where do students go to learn about digital technologies?

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

Data in the Future — Archived or Locked?

Prison terms for data retrieval?

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

Miscellaneous News Items

An irregular feature

To comment on an article, please email

the editor using editor as the user-

name, csanet.org as the domain-name,

and the standard user@domain format.

Index of Web site and CD reviews from the Newsletter.

Limited subject index for Newsletter articles.

Direct links for articles concerning:

- the ADAP and digital archiving

- CAD modeling in archaeology and architectural history

- GIS in archaeology and architectural history

- the CSA archives

- electronic publishing

- use and design of databases

- the "CSA CAD Layer Naming Convention"

- Pompeii

- pottery profiles and capacity calculations

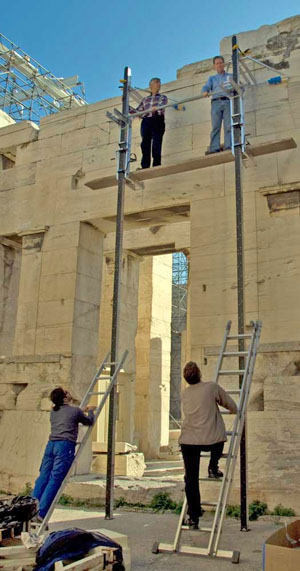

- The CSA Propylaea Project

- CSA/ADAP projects

- electronic media in the humanities

- Linux on the desktop

Search all newsletter articles.

(Using Google® advanced search

page with CSA Newsletter limit

already set.)

How Often Must We Reinvent the Wheel?

Harrison Eiteljorg, II

(See email contacts page for the author's email address.)

George Bernard Shaw said, "A life spent making mistakes is not only more honorable, but more useful than a life spent doing nothing." The more earthy Tallulah Bankhead said, "If I had to live my life again, I'd make the same mistakes, only sooner." I start with those two quotations in an attempt to focus the readers' minds on the value of errors. It is remarkably easy to make mistakes, but my concern is not about the frequency of mistakes so much as it is about the fact that the digital world makes it so easy to see my mistakes (and those of others) and to make clear my ineptitude (and that of others). Oddly, however, these mistakes are among my most important teachers; it seemed to me that both Shaw and Bankhead reflected that sentiment. That is, recognizing a mistake and learning from it is the often best form of education available — presuming the consequences of the mistakes aren’t too severe.

I am sure you have had similar experiences, but let me give you an example from my own work. When I first modeled the remains (and suggested restorations) of the older propylon on the Athenian Acropolis with AutoCAD®, there were so many layers (CAD parlance for data segments) that I found it all but impossible to keep them straight. The names I gave them — always logical at the time of their creation — were never suffiuciently memorable to let me keep them all straight. For instance, two blocks existed on one layer in their current positions and on another layer in the positions I thought they had occupied previously. I had also separated remains that were actual blocks from those that were simply cuttings in the bedrock. I needed ways to allow me to find the layer or layers I was looking for according to their attributes, and obvious-seeming names did not work. As a result, I developed a layer-naming strategy that permitted me to find individual layers or groups of layers according to a variety of attributes (a system that eventually morphed into the CSA Layer Naming Convention). Thus, struggling to use AutoCAD — and misusing it at the outset — eventually led to a way to use it much more effectively.

Similarly, early in my digital life I regularly had to move data from one program to another, and I found the typing (at which I am not expert, to say the least) of old data into a new document to be inefficient and error-prone. So I learned how to take data from one program and import them into another without needing to re-type anything. Indeed, learning how to do that has been a constant need with new software since the error-prone and time-consuming process of re-typing is something I try very hard to avoid. I now find that to be extremely important as a general process and try always to find ways to move data without needing to type anything a second time.

Other examples are legion. I write this not to rehearse all those times when I have learned from my mistakes but to suggest that all of us who labor in areas that are still developing, areas such as the digital realm in archaeology, must make a conscious effort to learn from our mistakes and to pass on that learning. We have too often been taught that the best thing to do with a mistake is to cover it up or bury it. In reality, the best thing to do is to accept it, fix it, and make certain that the lessons that can be taken from it are well learned.

This seems to me to be but one part of a major problem in the archaeological use of digital technologies. Many of us, pushing the frontier of the digital world, make errors that we are loath to admit, but failing to acknowledge the errors often condemns others to make the same errors. Even more lamentable, many also find themselves trying, almost blindly, to learn to apply new (to them) technology to their work without the benefit of knowing what has already been done, how it has worked, and how best to try to use the technology in question in light of past experience.

Here is one example from many years ago that I saw first-hand when I visited a project. AutoCAD had just been introduced at the particular site, and an architecture student (not an archaeology student) had been engaged to make the AutoCAD files of the excavation in the field during the work season. The young man thus tasked to use AutoCAD did not fully understand either AutoCAD or the needs of the excavation — at least not fully enough to make the technology fit the needs of the job. He did not know that he could place parts of his drawing on different layers (data segments) so as to keep various parts of the drawings visually distinct when required. As a result, all lines and other figures were drawn together on a single layer, regardless of whether the material was from different trenches, different strata, different areas of the excavation, or different work teams. It was therefore impossible to separate any trench from any other, any stratum from any other, or any team’s work from that of any other. This was an error that, fortunately, was seen rather early, but the only remedy was painstakingly to go back through all that had been drawn, moving lines and more complex shapes onto new layers so that the parts of the drawing could be seen separately or in sensible groups when required. (That was better than re-drawing everything from the beginning.)

That kind of error is not unusual when trying to apply new technology to a project for which that technology was not actually designed. There is, however, a real problem for those who wish to apply such technologies to their own work, especially new technologies that have been widely tested, used, and applied — and more especially when the new user is relatively isolated. Where can the new user go for the necessary advice and experience? How can the new user find such aid, if it even exists? How does the new user determine good versus poor resources?

I am a biased source, but I think the CSA resources are useful here. We have a large and diverse array of materials about the use of CAD in archaeology as well as various materials about databases and the more general book, Archaeological Computing. But how do potential users find them? How do they learn to trust them?

This is not a trivial question, and the number of archaeological projects trying to reinvent the proverbial wheel is far too high. Of course, the fast pace of technological change does not help. As soon as one becomes comfortable with a specific technology, there are likely to be changes that require further adjustments and reconsiderations. However, that should not be the case with relatively well-established technologies such as databases, GIS, and CAD. Nor is the pace of change such that digital photography needs to be re-learned (though new uses may crop up regularly). Even in these areas, though, it is far too common to find people re-inventing that damned wheel. Indeed, the last issue of the CSA Newsletter included an article about the use of CAD that spoke quite directly about the perceived need to learn how to apply CAD to a project without the benefit of any prior art.

As a result of the foregoing issues, I thought it might be useful to try to see what I could find on the web about one of those technologies, and it seemed most logical to use CAD for my experiment. So I tried two searches using Google, Bing, and Yahoo. First I searched for archaeology and CAD; then I searched for the same terms in reverse order, CAD and archaeology. These seemed the obvious choices, and there were enormous numbers of web pages found. In both instances Google found more than a million and a half relevant pages. Of course, nobody looks beyond the first few screens with such a set of search results; so the number of resources found is not particularly important. In addition, just appearing on the list means little or nothing. One promising resource, for instance, consisted only of four pages of text about using a digitizer. (Note that I am necessarily ignoring the problem that Google — and I assume the other two search engines to some degree — may or may not provide its best possible answers to my query. I may, instead, get those answers that the search engine, on the basis of prior searches, calculates that I really want.)

All the searches put the CSA CAD guide on the first page, and the Archaeology Data Service CAD guide generally made one of the first two pages. Most of the other results, though, were either commercial pages aiming to sell something; brief pages too short and shallow to be useful; or extremely simple, uninformative pages vaguely describing a particular use of CAD in archaeology. In addition, many of the resources found were long out of date. (The second search choice, putting CAD first, also turned up pages dealing with Chad and archaeology with both Bing and Yahoo. Apparently both assumed that spelling errors should be taken for granted.) Without fuller information about how many other web-based publications about CAD there are, though, this experiment does not prove a great deal, but it helps to illustrate the need for archaeology instructors to know about such resources and to be able to direct their students to them. Search engines in this case, as in so many, are not terribly helpful when the searcher hardly knows where to begin.

While writing this it occurred to me that it would be prudent, to say the least, to check for bibliographic assistance in Archaeological Computing, the downloadable book that includes chapters on databases, GIS, and CAD. The GIS chapter (by Fred Limp, not the author of this article) has some good bibliographic references. The chapters on CAD and databases (by the author of this article), on the other hand, have mostly what might uncharitably be called glib references to further readings. At least the chapter about CAD refers to the works of the author about CAD both at CSA and at the Archaeology Data Service in Britain.

It may, as a result, be possible for me to be critical without seeming to point fingers at others. Those fingers must be pointed at myself as well. Any archaeologist who works with students should, it seems safe to say, be prepared to recommend sources for students trying to learn to use digital technologies. If that is not possible, said archaeologist should at least be able to direct any student to the Archaeology Data Service and to the Guides to Good Practice sponsored by the ADS (and now by tDAR as well) as a starting point — and to Archaeological Computing here at the CSA website. It is one thing to make necessary mistakes; it is quite another to make consequential mistakes that can be avoided because others have made them before — others who not only learned from the process but attempted to pass on that learning via published resources. Not only should students be able to avoid mistakes, they should be able to learn from the work of their forebears. Thus, their teachers should be prepared to lead them to the appropriate resources concerning digital technologies, just as they are expected to lead them to appropriate bibliography in areas of archaeology with which they are not intimately familiar.

It may be argued that, in fact, archaeological computing should have a place in the curriculum of graduate students, a place analogous to that occupied by required foreign languages. Perhaps students should need to demonstrate competence in this area. I would not personally favor that, in part because the technology remains in a contant state of evolution and in part because the typical professor in a graduate program in archaeology may not be competent to examine students in this area. In addition, there is a limit to what may be piled onto the curriculum. Nevertheless, there must be some way for beginners to find their ways to good, useful, archaeologically-based resources to guide them with those technologies that they need. They must not be left to learn for themselves without the aid of all those errors so many of us have made already, not to mention all those superior ways to use the technologies that those of us who have used them have already learned. Reinventing the wheel is not useful when good wheels exist already.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

All articles in the CSA Newsletter are reviewed by the staff. All are published with no intention of future change(s) and are maintained at the CSA website. Changes (other than corrections of typos or similar errors) will rarely be made after publication. If any such change is made, it will be made so as to permit both the original text and the change to be determined.

Comments concerning articles are welcome, and comments, questions, concerns, and author responses will be published in separate commentary pages, as noted on the Newsletter home page.