| Vol. XXIII, No. 2 | September, 2010 |

Articles in Vol. XXIII, No. 2

Publishing Data in Open Context: Methods and Perspectives

Getting project data onto the web with Penelope.

-- Eric C. Kansa and Sarah Whitcher Kansa

Digital Antiquity and the Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR): Broadening Access and Ensuring Long-Term Preservation for Digital Archaeological Data

A new and ambitious digital archaeology archive.

-- Francis P. McManamon, Keith W. Kintigh, and Adam Brin

§ Readers' comments (as of 10/4/2010)

Website Review: Kommos Excavation, Crete

Combining publication media to achieve better results.

-- Andrea Vianello

The New Acropolis Museum: A Review

Some pluses, some minuses.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

Aggregation for Access vs. Archiving for Preservation

Two treatments for old data.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

Miscellaneous News Items

An irregular feature.

To comment on an article, please email

the editor using editor as the user-

name, csanet.org as the domain-name,

and the standard user@domain format.

Index of Web site and CD reviews from the Newsletter.

Limited subject index for Newsletter articles.

Direct links for articles concerning:

- the ADAP and digital archiving

- CAD modeling in archaeology and architectural history

- GIS in archaeology and architectural history

- the CSA archives

- electronic publishing

- use and design of databases

- the "CSA CAD Layer Naming Convention"

- Pompeii

- pottery profiles and capacity calculations

- The CSA Propylaea Project

- CSA/ADAP projects

- electronic media in the humanities

- Linux on the desktop

Digital Antiquity and the Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR): Broadening Access and Ensuring Long-Term Preservation for Digital Archaeological Data

Francis P. McManamon, Executive Director, Digital Antiquity, Keith W. Kintigh, Member of the Board of Directors, Digital Antiquity, and Adam Brin, Director of Technology, Digital Antiquity

(See email contacts page for the author's email address.)

Introduction

Digital Antiquity was established in 2009 as an organization with two primary goals. One goal is to expand dramatically access to digital files related to a wide range of archaeological investigations and topics, e.g., archives and collections; field studies of various scales and intensities; and historical, methodological, synthetic, or theoretical studies (Digital Antiquity 2010). In order to accomplish this goal, Digital Antiquity maintains a repository for digital archaeological data.

The repository, known as the Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR) is accessible broadly. Through a web interface users worldwide are able to discover data and documents relevant to their interests. Individuals and organizations may contribute archaeological digital data to the repository by uploading their own data and documents and creating appropriate metadata for the digital objects they contribute. Users who register and agree to adhere to a set of conditions regarding appropriate use of data and recognition of the data depositors may download documents and data sets. The wider access provided to a richer array of documents and databases permits scholars to develop interpretations and communicate knowledge of the historic and long-term human past more effectively. This broader access also enhances the management and preservation of archaeological resources.

Browsing or searching the tDAR repository enables users to identify digital documents, data sets, images, and other kinds of archaeological data for research, learning, teaching, and simply to satisfy their own curiosity about the past as revealed by archaeological research and interpretations. The tDAR repository permits registered users to download data files, while maintaining the confidentiality of legally protected information and the privacy of digital resources on which contributing researchers still are working. The tDAR repository provides researchers with new avenues to discover and integrate information relevant to topics they are studying. Currently users can search tDAR for digital documents, spreadsheets, and data sets. In the near future, images also will be available and, ultimately, other digital file types, for example GIS, GPS, CAD, 3D images and other data resources from archaeological projects spanning the globe. For data sets, users also can use data integration tools in tDAR to simplify and illuminate comparative research.

The second major goal of Digital Antiquity is the long-term preservation of the data contributed to tDAR. Digital Antiquity is dedicated to ensuring the long-term preservation of digital archaeological data through procedures that check file integrity and correct any deterioration over time. Our procedures also provide for migration of data file formats from current standard types to new file standards as software and hardware computer technology develops. We aspire to meet the criteria for trusted digital repositories (OCLC and CRL 2007), which are required in order to ensure the long-term preservation and continued access to archived data. In the case of archaeological data, which document the archaeological record, the digital files encapsulate the combined efforts of the archaeological and scientific community, the public and private funds used to carry out research, as well as descriptions and analyses of the material from the ancient and historical cultures studied.

As part of our commitment to long-term preservation, our strategy for the tDAR repository includes growth and improvement. We conduct regular maintenance and develop enhancements of different aspects of our procedures, repository functions, and user interface. These improvements are being planned in cooperation with an advisory team including archaeologists, supporting agencies, preservation experts, and staff to incorporate advances in research methods, digital preservation, and technology.

The Need for Digital Archiving

Much of the information produced by archaeological research over the past century exists in technical, sometimes lengthy, limited-distribution reports scattered in libraries, museums, repositories, and offices around the world. The data that underlie these reports are encoded on computer cards, magnetic tapes, floppy disks, and CDs quietly and steadily degrading on book shelves and in file cabinets and desk drawers, while the technology to retrieve them and the human knowledge to make them meaningful rapidly disappears (Eiteljorg 2004; Michener et al. 1997). Rather than systematically archiving computerized information so that it can remain useable, museums and other repositories typically treat the media on which the data are recorded as artifacts – storing them in boxes on shelves. Childs and Kagan (2008) found that only a few of the 180 archaeological repositories that responded to their recent survey reported charging fees to upload digital data from the collections and records they curated to computers for preservation and access. By far, the most common preservation treatment for digital data used by the repositories that responded to the Childs and Kagan survey preserves the media on which the digital data files are stored but leaves the data on the media actually inaccessible. This physical curation is an inadequate long-term preservation approach as computer software and hardware change and as the bits on the magnetic and optical media gradually, but inevitably "rot."

Much of the archaeological work in the United States involves federal funds, lands or permits and is subject to federal law. Federal agencies already have the legal responsibility (36 C.F.R. 79; Sullivan and Childs 2003:23-38) to require curation of archaeological collections and associated records, including digital data, in a form that is accessible and will survive in perpetuity. Yet, despite federal mandates requiring preservation and access to digital data, the vast majority is difficult or impossible to access and will not be preserved in the formats in which they currently reside. The existing mandates already are in place to justify widespread professional participation in efforts to improve access to data and its long-term preservation. However, compliance with the mandates requires the existence of repositories capable of meeting the data access and curation needs.

The intertwined problems of data access, preservation, and synthesis are not new to archaeology. In the late 1990s, a series of meetings and panels were sponsored by the Society for American Archaeology, the Society of Professional Archaeologists (now the Register of Professional Archaeologists), and the National Park Service on the general topic of "Renewing Our National Archaeological Program." Improving the management of archaeological information through greater data access and synthesis was one of the major topics covered in this effort (Lipe 1997; McManamon 2000).

Neither are the challenges of data access and preservation unique to archaeology. The 10 September 2009 issue of Nature began with an editorial calling for broader sharing of data and its long term preservation and related reports on data access and preservation challenges (Nature 2009; Nelson 2009; Schofield et al. 2009; Toronto International Data Release Workshop Authors 2009). The editorial cited particular successes:

Pioneering archives such as GenBank have demonstrated just how powerful such legacy data sets can be for generating new discoveries - especially when data are combined from many laboratories and analysed in ways that the original researchers could not have anticipated (Nature 2009a:145).

However, the editorial emphasized that most scientific disciplines

still lack the technical, institutional, and cultural frameworks required to support such open data access—leading to a scandalous shortfall in the sharing of data by researchers. This deficiency urgently needs to be addressed by funders, universities, and researchers themselves…[Furthermore] funding agencies need to recognize that preservation of and access to digital data are central to their mission, and need to be supported accordingly (Nature 2009:145).

Also in 2009 the National Academies in the United States released a book-length report promoting efforts to ensure the integrity, accessibility, and stewardship of digital research data (National Academies 2009). At the same time as we consider how to improve curation of digital legacy data, we must also look forward. A substantial amount of public archaeological work is carried out annually. Federal agencies report approximately 50,000 field projects involving archaeological resources conducted in the United States, mostly by cultural resource management firms or agency staff (Departmental Consulting Archeologist 2009). Given the volume of data and reports produced each year, even archaeologists working in the same area often are unaware of important results that others have already reported. Archaeological studies are generating loads of data, However, without effective access to these data and documents, they cannot be used efficiently to advance knowledge of the past. The difficulty of sharing information about and from existing research is exacerbated by the demographic transition underway in the ranks of professional archaeologists.

Large numbers of archaeologists entered the profession in the 1960s and 1970s. These individuals are retiring or passing away. As they do so, replacements are not sufficient to keep up with the needs of the profession as regards gathering and protecting the data regarding field projects and scholarship. In addition, documenting important background information (metadata) about the data and documents that this professional cohort created is essential before they are no longer available to provide this information.1

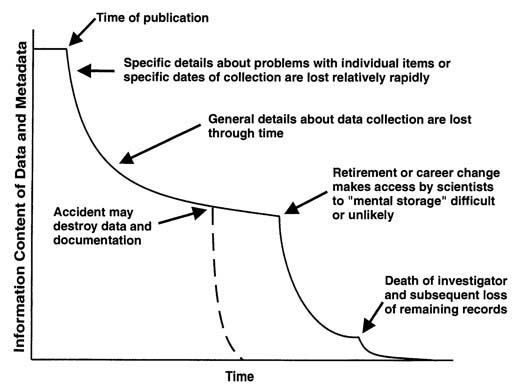

It is important to capture for long-term preservation and access the digital data associated with the work carried out by the cohort of retiring archaeologists. Accessing the information by relying on the memories of individuals, no matter how prodigious these memories might be, will be impossible once these individuals are no longer available. The problem of obtaining accurate and detailed metadata is an old one and not confined to archaeology or even to the social sciences. The ecologist William K. Michener and his colleagues created a telling illustration (Figure 1) in their 1997 article on the topic (Michener et al. 1997).

Today, a great deal of time is spent searching for and acquiring relevant reports. Once found, more time is required to hunt for key data in volume after volume of hard copy reports that sometimes extend to more than a thousand pages. Yet the ability to reanalyze existing data can make present-day investigations more productive and has the potential to help researchers and scholars to recognize and reduce costly and unnecessarily redundant projects.

Like many of the topics already discussed, this problem is not unique to archaeology. In late 2009, President Obama directed the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to investigate, with substantial public participation, how federally-generated research data on a wide range of subjects can be made more easily accessible to all Americans. From December of last year to the end of January 2010, OSTP collected public suggestions and statements on this topic (Kaiser 2010; OSTP 2010). OSTP has not yet announced (as of September 2010) any conclusions or proposed next steps that they have derived from studying the 400-plus responses to their request for comments. The OSTP effort is part of the President's "Open Government Initiative," which directs federal department and agencies to improve the quality of government information and make it available online and to create a culture of open government through policy frameworks and practice (Orszag 2009).

Of direct relevance for archaeologists, the National Science Foundation (NSF), responding to both the presidential directive and interest within the scientific community on wider access to research data, announced that all proposals for NSF funding will be required to include "data management plans." In these sections of the proposals, researchers will describe how the data resulting from their proposed investigation will be shared widely and also how it will be preserved for future access and use. These policy emphases from the federal government are very much in line with the goals and mission of Digital Antiquity and the functions being carried out by the tDAR repository. Obviously, in order to effect the wider access to and long-term preservation of data and documents created by funded NSF research, some of the project funds will need to be devoted to placing the digital objects in a trusted digital repositiory.

Organization

Digital Antiquity is a collaborative multi-institutional organization involving archaeologists, computer scientists, and librarians at the University of Arkansas, Arizona State University, the Pennsylvania State University, the SRI Foundation, the University of York's Archaeology Data Service, and Washington State University. The organization's office is based at Arizona State University (ASU) where Digital Antiquity is sponsored and supported jointly by the School of Human Evolution and Social Change (Anthropology) and the Arizona State University Libraries. At ASU, Digital Antiquity is located in the Hayden Library, the main library of the university, on the Tempe campus.

Digital Antiquity is the direct product of a multi-institutional effort to plan a sustainable digital repository for archaeological documents and data that was funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The Mellon Foundation has now funded the implementation of Digital Antiquity and tDAR in response to a 2008 proposal that grew out of the multi-institutional planning grant. The proposal was authored by Keith W. Kintigh (Arizona State University), Jeffrey Altschul (SRI Foundation), John Howard (then Associate Librarian at Arizona State University, now Librarian at University College, Dublin), Timothy Kohler (Washington State University), Frederick Limp (University of Arkansas), Julian Richards (University of York), and Dean Snow (The Pennsylvania State University).

Digital Antiquity confronts several challenges that must be solved in order to succeed as a sustainable digital repository. Its business plan envisions either a transition from an university center incubated by Arizona State University into an independent not-for-profit or into a unit of an established non-profit with compatible goals that can manage Digital Antiquity's services and data assets in the long term. Digital Antiquity's business plan is based on a model in which those who are responsible for archaeological investigations will pay a fee for the deposit of data and documents in the tDAR repository. In return, long-term preservation of the data will be assured and access to the data and documents will be freely available over the Internet, with controlled access to confidential data.

The Mellon Foundation implementation grant has enabled the establishment of Digital Antiquity as an independent organization. It is planned that, for a four-to-five year startup period, offices of Digital Antiquity will be hosted by Arizona State University. In November 2009, Francis P. McManamon, formerly Chief Archeologist of the National Park Service and Departmental Consulting Archeologist for the Department of the Interior, began working as the full-time Executive Director. In June, 2010, Adam Brin, formerly with the California Digital Libraries of the University of California and the Information Systems of the Tri-Colleges Libraries at Bryn Mawr, Haverford, and Swarthmore Colleges in the Philadelphia area, began working as Technology Director. The staff also includes a full time software engineer and several part-time digital data curators.2

The Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR)

In 2004. the National Science Foundation (Grant #0433959) funded a workshop focused on the integration and preservation of structured digital data derived from archaeological investigations. The workshop included 31 distinguished participants from archaeology, physical anthropology, and computer science. The workshop report concluded

for archaeology to achieve its potential to advance long-term, scientific understandings of human history, there is a pressing need for an archaeological information infrastructure that will allow us to archive, access, integrate, and mine disparate data sets (Kintigh 2006:567).

A subsequent NSF grant (0624341) funded the development of a prototype of tDAR, the digital repository now maintained and expanded as a part of the Digital Antiquity implementation. Digital Antiquity's key objectives include fostering the use of tDAR and ensuring its financial, technical, and professional sustainability. Use of tDAR has the potential to transform archaeological research by providing direct access to current and historic digital data along with powerful tools to analyze and reuse it.

Development and testing of the tDAR prototype was led by Kintigh and involved a team that included ASU archaeologists (Ben Nelson, Margaret Nelson, and Katherine Spielmann) and computer scientists (K. Selçuk Candan and Hasan Davulcu) as well as the Associate University Librarian (John Howard). Additional enhancements are being developed by the current Digital Antiquity team, including Kintigh, Spielmann, Adam Brin, Allen Lee, Matt Cordial, and James deVos.

The tDAR software and hardware choices have been made with flexibility, scaling, and longevity as the primary concerns. In addition, tDAR has chosen to use Open Source tools to the greatest extent possible.3

The tDAR repository encompasses digital documents and data derived from ongoing archaeological research, as well as legacy data and documents collected through more than a century of archaeological research. The repository provides for long-term preservation and easy discovery and access to the digital objects within it.

The information resources preserved and made available by tDAR are documented by detailed metadata submitted by the user as part of the procedures in uploading the data and documents into the repository. Metadata may be associated generally with a project or specifically with an individual information resource (such as a database, document or spreadsheet). Descriptive metadata are tailored to the nature of archaeological data. This metadata both enables effective resource discovery during browse and search by users and provides the detailed semantic information needed to permit sensible scientific reuse of the data. The metadata elements encode spatial, temporal, cultural, material, and other keywords, well as detailed information regarding authorship, sponsorship, and other sorts of credit. Appropriate citation and acknowledgements must accompany any use of downloaded data as a requirement of the tDAR user agreement. For documents, tDAR maintains and delivers full standard citation information. For databases tDAR maintains detailed metadata for each column of each table and for individual values of nominal variables.

Metadata entry is designed to take full advantage of contributors' knowledge of their data. Web forms guide data contributors through a streamlined process of metadata entry and file upload. For data sets, this includes documentation of individual data table columns and nominal values with mappings to coding sheets and ontologies. To facilitate metadata entry and maintenance, digital objects may be organized into "projects" whose vocational, administrative, and other metadata elements are shared by the project's reports, databases, etc. Each specific object "inherits" the project metadata unless it is given more specific metadata.

In its present release, tDAR accommodates databases, spreadsheets, and documents in a limited number of formats. While the digital files are maintained as submitted, they are also - whenever necessary - transformed into a format that can be sustained in the very long term (e.g. translation of Word files into a more sustainable PDF/A format). Planned development includes the expansion of the data and document formats accepted, as well as the inclusion of images, GIS, CAD, LiDAR and 3D scans, and other remote sensing data.

The inclusion of these more exotic forms of data awaits the completion of another part of Digital Antiquity's work, updating of "best practices" guidelines for the creation and preparation of archives for archaeological digital data. These guidelines build on the well-developed guideline series published by the Archaeology Data Services (ADS) in the United Kingdom (http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/project/goodguides/g2gp.html). Julian Richards, Director of ADS, and Fred Limp of the University of Arkansas are leading the preparation of these guidelines. Readers who are particularly interested in the revisions to the Guides under way are encouraged to review and provide comments on the drafts at http://guides.archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/.

Individual repository data sets and documents will all have persistent Universal Resource Indicators (URIs) that will provide permanent, citable web addresses. A development is planned to ensure that when content is revised, earlier content is automatically versioned, so that the exact content as of a given date always can be retrieved. Sensitive information, such as site locations, can be restricted to qualified individuals. Investigators also can mark content (notably for ongoing projects) as "embargoed" for a defined period, prior to a public release. All digital objects are stored in the original format in which they were submitted and in a preservation format, if different. The original format is maintained at a bit level but its usability with future software is not assured. The preservation format is selected to maintain a high level of stability though long-term migration. To maintain a high level of usability, a derivative format may also be created to ensure compatibility with contemporary software. For example, Microsoft Excel files (.xls) are maintained as submitted, but are transformed to ASCII CSV (comma separated values) as a preservation format. In addition, tDAR will migrate common document, spreadsheet, and data set file types to future versions for dissemination as these platforms develop and become standard.

Access to the repository content is provided through a Web interface. Most tDAR metadata elements are indexed, and both basic and advanced search capabilities are provided (including a Google Maps-based spatial search). Once a user has identified an information resource of interest, it may be downloaded contingent on the acceptance of a user agreement. Users must agree to provide appropriate credit with any reuse of the data and to refrain from any use that might endanger archaeological resources. With the exception of confidential data (primarily, legally protected archaeological site locations) and data temporarily embargoed by their contributors, all tDAR data are freely available over the web. A development is planned so that all document and data downloads are provided with appropriate citation information.

The development of tDAR, an easily accessible archive of digital archaeological data, offers the potential for more efficient and effective background research of past archaeological work, saving time and money for public archaeological management and preservation efforts, as well as for scholarly research. This online archive also will permit broad, comprehensive upgrading of digital data as new platforms for data storage and retrieval develop. To achieve this potential, archaeological practice must be transformed so that the digital archiving of data and the metadata necessary to make it meaningful become a standard part of all archaeological project workflows.

Conclusion

Digital Antiquity represents an exciting opportunity for advancing knowledge through improved and wider-ranging comparative analysis of archaeological data and easier synthesis of these data. Through tDAR, Digital Antiquity provides a mechanism for public agencies and other institutions to satisfy their legal mandates and professional responsibilities to provide access to the digital records of archaeological research and to effect long term curation using professional archival practices. Digital Antiquity will not only store data, but will provide the tools required by archaeologists to identify and access those data. It is anticipated that as the tDAR repository becomes more fully populated, consulting archaeology firms and public agencies, as well as academic archaeologists, will be able to work much more effectively. It will enormously increase the accessibility - and impact - of the important work that the consulting firms and agencies do in managing, preserving, and protecting the archaeological record. Indeed, widespread digital access to archaeological data of the sort provided by tDAR has the potential to transform the practice of archaeology by enabling synthetic and comparative research on a scale heretofore impossible. To succeed, however, cooperation and coordination throughout the discipline is needed. Those of us involved in Digital Antiquity look forward to working through mutually beneficial partnerships with diverse organizations and individuals to achieve the potential that the initiative offers.

-- Francis P. McManamon, Keith W. Kintigh, and Adam Brin

Acknowledgments: Portions of this text appeared in an earlier article in the Society for American Archaeology Archaeological Record (McManamon and Kintigh 2010). We appreciate and have used the comments and suggestions of our colleagues: Jeff Altschul, Terry Childs, Tim Kohler, Fred Limp, Peggy Nelson, Julian Richards, and Dean Snow, on an earlier draft of this article. Other colleagues who contribute their efforts by working on tDAR and Digital Antiquity activities include: Allen Lee, Matt Cordial, Shelby Manney, Katherine Spielmann, Mary Whelan, and Josh Watts. The Digital Antiquity initiative and tDAR, the Digital Archaeological Record, have been funded by grants from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and by the National Science Foundation (0433959, 0624341). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation or the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and by the National Science Foundation (0433959, 0624341). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation or the Mellon Foundation.

Notes:

The permanent archaeological workforce of the Forest Service (FS) and National Park Service (NPS) totals about half of all government archaeologists (Table 1; 496/974= 50.9%). FS and NPS report that 15 percent of their permanent archaeological professionals were eligible to retire in 2008 (Table 2). Between 2008 and 2013, 25 percent of the FS archaeologists, 27 percent of the NPS archaeologists, and 36 percent of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) archaeologists will become eligible to retire. Between 53 and 55 percent of the professional archaeologists currently employed by the BLM, NPS, and FS already are eligible or will become eligible to retire by 2017 (Table 2).

At present, the hiring of new career professionals is not sufficient to replace the senior professionals who have already or soon will be retiring. For example, the NPS hired nine professional archaeologists in the five-year period between 2003 and 2007. During the same period, however, the NPS lost 23 archaeologists through retirement. This rate of replacement is insufficient to maintain the current level of professional archaeologists employed by federal agencies to comply with the legal and regulatory requirements for archaeological resource stewardship. If the NPS rate of professional hiring (9/5 = 1.8 per year) reflects the wider status quo in hiring and replacing federal agency professional archaeologists, during the next decade, the major land-managing agencies will have substantially fewer professional archaeologists to ensure the interpretation, preservation, and protection of some of America's most important archaeological resources (Table 3).

Table 1. Permanent Positions-Federal Agency Archaeologists: Ages (data from 2007 and 2008).

Age

| Federal Agency | |||||||

| Archaeologists | Total | 20 - 29 | 30 - 39 | 40 - 49 | 50 - 59 | 60 - 69 | 70 - 79 |

| Forest | 337 | 8 | 55 | 94 | 157 | 23 | 0 |

| Service* | 2% | 16% | 28% | 47% | 7% | 0% | |

| National | 159 | 1 | 33 | 43 | 70 | 11 | 1 |

| Park Service** | 1% | 21% | 27% | 44% | 7% | 1% | |

| All Federal*** | 974 | 21 | 167 | 252 | 437 | 97 | No data |

| Agencies | 2% | 17% | 26% | 45% | 10% |

* Forest Service data on permanent employees (as of 2 January 2008), courtesy of Mike Kaczor, Federal Preservation Officer, Forest Service.

** National Park Service data on permanent employees (as of 31 March 2007), courtesy of NPS Personnel Office.

*** Data on all Federal permanent archaeologists (as of September 2007), from the Office of Personnel and Management, www.fedscope.opm.gov/.

Table 2. Permanent Positions-Federal Agency Archaeologists: Years to Retirement (date from 2007 and 2008).

Retirement Eligibility

| Federal Agency | Next | Next | Next | Next | Next | Next | |||

| Archaeologists | Now | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | >30 (est.) | Total |

| Forest | 23 | 85 | 72 | 49 | 45 | 31 | 24 | 8 | 337 |

| Service* | 7% | 25% | 21% | 15% | 13% | 9% | 7% | 2% | |

| National | 12 | 43 | 32 | 18 | 31 | 19 | 4 | no data | 159 |

| Park Service** | 8% | 27% | 20% | 11% | 19% | 12% | 3% | no data | |

| Bureau of | no data | 70 | 35 | 25 | 9 | 20 | 7 | 28 | 194 |

| Land Management*** | no data | 36% | 18% | 13% | 5% | 10% | 4% | 14% |

* US Forest Service data on permanent employees (as of 2 January 2008), courtesy of Mike Kaczor, Federal Preservation Officer, Forest Service.

** National Park Service data on permanent employees (as of 31 March 2007), courtesy of NPS Personnel Office.

*** Bureau of Land Management data (as of 18 March 2007), courtesy of Robin Burgess and Bekki Lasell, BLM Washington Office.

Table 3. Projected Positions - Permanent Federal Agency Archeologists in 2017.

Projected Future Professional Archaeologists in Federal Agencies

| Federal Agency | Estimated 2017 | |||

| Archaeologists | Current* | New Hires** | Retirements*** | Professional Staff**** |

| US Forest Service | 337 | 18 | 180 | 175 |

| National Park Service | 159 | 18 | 87 | 94 |

| Bureau of Land Management | 194 | 18 | 105 | 107 |

* Numbers of permanent archeologists employed by Federal agencies (as in Table 1).

** Estimated number of archeologists who will be hired during the ten-year period, 2007-2017, using the annual hiring rate for new National Park Service (NPS) archeologists (9 new hires in 5 years = 1.8 hires/year) documented between 2003 and 2007 by NPS Personnel Office.

*** Estimated number of retirements of archeologists during the ten-year period, 2010-2017, if retirements occur when retirement eligibility is reached by individuals (as in Table 2).

**** Estimated number calculated as: Current + New Hires – Retirements.

Return to text.Members of the Board of Directors, Digital Antiquity

- Sander van der Leeuw, Director and Professor, School of Human Evolution & Social Change (SHESC), Arizona State University (ASU) [chair]

- Carol Ackerson, Senior Associate, Girl Scouts Arizona Cactus-Pine Council, Inc.

- Jeffrey Altschul, President, SRI Foundation, and Chairman, Statistical Research, Inc.

- Kim Bullerdick, Owner, BI, L.L.C.

- John Howard, University Librarian, University College, Dublin

- Keith Kintigh, Associate Director and Professor, SHESC, ASU

- Tim Kohler, Regent's Professor, Department of Anthropology, Washington State University

- Fred Limp, Leica Geosystems Chair and University Professor of Anthropology, Geosciences and Environmental Dynamics and Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies, University of Arkansas

- Harry Papp, L. Roy Papp & Associates L.L.P.

- Julian Richards, Chair, Department of Archaeology and Director, Archaeology Data Service, University of York

- Dean Snow, Professor, Department of Anthropology, The Pennsylvania State University

Members of the Science Advisory Board, Digital Antiquity

- Brian Crane, Director, Cultural Resources Division, Versar, Inc.,Springfield, Virginia

--Cultural Resource Management (CRM) Archaeology, Eastern US, DOD nominee - Katherine (Kitty) Emery, Assistant Curator, Florida Museum of Natural History, & Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Florida.

--Museums, Mesoamerica, Fauna - Sebastian Heath, Archaeological Institute of America

--Classical Archaeology, Mediterranean, Archaeological Institute of America nominee - Eric Kansa, Executive Director, Information Service and Service Design Program, University of California at Berkeley, Board of Directors, Alexandria Archive Institute

--Archaeological Informatics - Worthy Martin, Associate Professor, Computer Science, University of Virginia

--Computer Science - Fraser Neiman, Director of Archaeology, Monticello & Lecturer, Department of Anthropology and Architectural History, University of Virginia, Director DAACS

--Historical Archaeology - Vincas (Vin) Steponaitis, Director, Research Laboratory of Archaeology, and Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of North Carolina, Former SAA President

--Academic Archaeology & Museums, Academic Archaeology, Southeast US - Herbert Van de Sompel, Team Leader, Digital Library Research & Prototyping Team, Los Alamos National Laboratory

--Informatics - Willeke Wendrich, Associate Professor on Egyptian Archaeology, Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, University of California, Los Angeles

--Academic Archaeology, Egypt - Thomas Whitley, Vice President, Brockington & Associates, Norcross, Georgia

--CRM archaeology, Southeast - Vacant: Bioarchaeology

- Vacant: Government Archaeology

Digital Antiquity has three RHEL virtual machines maintained by ASU’s Engineering Technical Services Server-On-Demand service with 1 TB disk shares (expandable as needed) on each VM that are backed up to an off-site location. We have a production server VM, a staging server VM, and a development server VM. In addition to the primary copy of the data being stored on redundant disks behind a cluster of enterprise-class Network Attached Storage filers with failover capability, a backup copy of the data is created daily on a separate disk storage system in a separate building to provide protection and rapid restore from any data loss. Snapshots of both the primary and backup copies of the data are taken daily, and access to the snapshots on the primary volume is available to users to make the recovery of accidentally deleted files as seamless as possible. Daily snapshots are retained for a month, and monthly snapshots are retained for four months. In the near future, we plan to implement one of the out-of-region or cloud backup options we are now investigating. The tDAR codebase is licensed under an Apache 2.0 License.

Return to text.References:

Childs, S. Terry and Seth Kagan 2008. "A Decade of Study into Repository Fees for Archeological Collections," Studies in Archeology and Ethnography Number 6. Archeology Program, National Park Service, Washington, DC. http://www.nps.gov/archeology/PUBS/studies/STUDY06A.htm, accessed 28 November 2009

Departmental Consulting Archeologist 2009. The Secretary of the Interior's Report to Congress on the Federal Archeological Program, 1998-2003. Archeology Program, National Park Service, Washington, DC. http://www.nps.gov/archeology/SRC/src.htm, accessed 28 November 2009>.

Digital Antiquity 2010. "Digital Antiquity Policies and Procedures: Policies and Procedures Related to the Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR)," Copy of file, Center for Digital Antiquity, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ.

Eiteljorg, Harrison, II 2004. "Archiving Digital Archaeological Records," In Our Collective Responsibility: The Ethics and Practice of Archaeological Collections Stewardship, edited by S. Terry Childs, pp. 67-73. Society for American Archaeology, Washington, DC.

Kaiser, Jocelyn 2010. "White House Mulls Plan to Broaden Access to Published Papers," Science 327:259.

Kintigh, Keith (editor) 2006. "The Promise and Challenge of Archaeological Data Integration," American Antiquity 71(3):567-578.

Lipe, Bill 1997. Report on the Second Conference on Renewing Our National Archaeological Program, February 9-11, 1997. http://www.saa.org/AbouttheSociety/GovernmentAffairs/NationalArchaeologicalProgram/tabid/240/Default.aspx, accessed 1 December 2009.

McManamon, Francis P. 2000. Renewing the National Archaeological Program: Final Report of Accomplishments. A Report to the Board of the Society for American Archaeology from the Task Force Chair. Society for American Archaeology, Washington, DC. http://www.saa.org/AbouttheSociety/GovernmentAffairs/NationalArchaeologicalProgram/tabid/240/Default.aspx, accessed 1 December 2009.

McManamon, Francis P. and Keith W. Kintigh (2010) "Digital Antiquity: Transforming Archaeological Data into Knowledge," The SAA Archaeological Record 10(2):37-40.

Michener, W.K., Brunt, J.W., Helly, J.J., Kirchner, T.B. and Stafford, S.G. 1997. "Nongeospatial Metadata for the Ecological Sciences," Ecological Applications 7: 330-342.

National Academies 2009. Ensuring the Integrity, Accessibility, and Stewardship of Research Data in the Digital Age, The National Academies Press, Washington, DC.

National Science Foundation 2010. Scientists Seeking NSF Funding Will Soon Be Required to Submit Data Management Plans. National Science Foundation Press Release 10-077. Washington, DC. http://www.nsf.gov/news/news_summ.jsp?cntn_id=116928, assessed September, 2010.

Nature 2009. Editorial: "Data's Shameful Neglect," Nature 461(7261):145.

Nelson, Bryn 2009. "Data Sharing: Empty Archives," Nature 461(7261):160-163.

OCLC (Online Computer Library Center, Inc.) and CRL (The Center for Research Libraries) 2007. Trustworthy Repositories Audit and Certification: Criteria and Checklist, version 1.0. OCLC, Dublin, OH and CRL, Chicago, IL.

Orszag, Peter R. 2009. Open Government Directive. Memorandum to the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies (8 December 2009), Office of Management and Budget, Executive Office of the President, Washington, DC.

OSTP (Office of Science and Technology Policy) 2010. OSTP Public Access Policy Forum. Office of Science and Technology Policy, Washington, DC. http://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/eop/ostp/public-access-policy (accessed 29 April 2010).

Schofield, Paul N., Tania Bubela, Thomas Weaver, Stephen D. Brown, John M. Hancock, David Einhorn, Glauco Tocchini-Valentini, Martin Hrabe de Angelis, and Nadia Rosenthal 2009. "Opinion: Post-publication Sharing of Data and Tools," Nature 461(7261):171-173.

Sullivan, Lynne P. and S. Terry Childs 2003. Curating Archaeological Collections: From the Field to the Repository AltaMira Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

Toronto International Data Release Workshop Authors 2009. "Opinion: Prepublication data sharing," Nature 461(7261): 168-170.

All articles in the CSA Newsletter are reviewed by the staff. All are published with no intention of future change(s) and are maintained at the CSA website. Changes (other than corrections of typos or similar errors) will rarely be made after publication. If any such change is made, it will be made so as to permit both the original text and the change to be determined.

Comments concerning articles are welcome, and comments, questions, concerns, and author responses will be published in separate commentary pages, as noted on the Newsletter home page.