| Vol. XXIII, No. 2 | September, 2010 |

Articles in Vol. XXIII, No. 2

Publishing Data in Open Context: Methods and Perspectives

Getting project data onto the web with Penelope.

-- Eric C. Kansa and Sarah Whitcher Kansa

Digital Antiquity and the Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR): Broadening Access and Ensuring Long-Term Preservation for Digital Archaeological Data

A new and ambitious digital archaeology archive.

-- Francis P. McManamon, Keith W. Kintigh, and Adam Brin

§ Readers' comments (as of 10/4/2010)

Website Review: Kommos Excavation, Crete

Combining publication media to achieve better results.

-- Andrea Vianello

The New Acropolis Museum: A Review

Some pluses, some minuses.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

Aggregation for Access vs. Archiving for Preservation

Two treatments for old data.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

Miscellaneous News Items

An irregular feature.

To comment on an article, please email

the editor using editor as the user-

name, csanet.org as the domain-name,

and the standard user@domain format.

Index of Web site and CD reviews from the Newsletter.

Limited subject index for Newsletter articles.

Direct links for articles concerning:

- the ADAP and digital archiving

- CAD modeling in archaeology and architectural history

- GIS in archaeology and architectural history

- the CSA archives

- electronic publishing

- use and design of databases

- the "CSA CAD Layer Naming Convention"

- Pompeii

- pottery profiles and capacity calculations

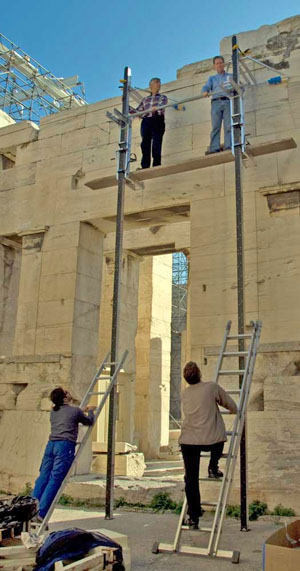

- The CSA Propylaea Project

- CSA/ADAP projects

- electronic media in the humanities

- Linux on the desktop

The New Acropolis Museum: A Review

Harrison Eiteljorg, II

(See email contacts page for the author's email address.)

The new museum in Athens for housing the materials from the Acropolis has now been open for some time. I had the opportunity to visit for the first time in June of this year and was able to visit the museum twice on successive days. No photographs are included here, but a good number may be found on the museum's web site at http://www.newacropolismuseum.gr/eng/building_gallery/building_gallery.html.

About the exterior of the building (designed by Bernard Tschumi, winner of the fourth! international competition for the design, with Michael Photiadis as an Athenian associate) there is little to be said. The compromises required as archaeological excavation on the site made the location more and more problematic must be seen as excuses for a building that is remarkably unattractive to this viewer. In particular, in the land of columns with entasis and inclination, it was shocking to see a building supported by massive, cylindrical concrete "columns" that had all the subtlety and grace of a modern army tank. It is not even possible to call them columns without using quotation marks.

As one approaches the building one sees the excavated remains through glass portions of the entrance floor. The glass has black dots in a pattern well-chosen to let one see clearly without feeling uneasy about the sureness of one's footing. It is a very effective and welcome way to permit the excavation work to continue while the building is in use and to let visitors see the remains. However, it also represents a lost opportunity. The signage for the excavation, such as it is, is minimal, and a wonderful opportunity to educate visitors is wasted. Whereas visitors might have been told a great deal about how the excavation happened and how the building was able to rise above it - or how the strata in the area were identified - or what the individual rooms/buildings contained - or how those rooms/buildings function and how we know that - or . . . , the single sign offers only a vague and general description of what remains. Of all the places in the world where one might take advantage of the opportunity to teach, this seems among the best. Such a waste.

The top floor of the museum is oriented differently from the lower floors, and the lower floors do not have equivalent spaces open for display. As a result, each floor's display space is somewhat differently related to the central core containing stairs and ramps, restrooms, elevators, and fire exits. (Checking this out with the floorplan from the museum's web site, I noted that there is a virtual reality theater in the museum. It is located, however, in such an out-of-the-way place that it is hard for me to imagine its effective use.)

Entering the building, one sees little or nothing of antiquity. Instead there are large counters for the ticket-sellers to the right and a shop to the left with a cafe behind it. (For those who have visited another important new museum, The National Museum of the American Indian at the Smithsonian, the sense of the commercial being dominant will be familiar.) Another restaurant; this one larger, offering more food, and including an outdoor eating area; lies on the floor between the first display floor and the Parthenon level; on that in-between level there is no display space at all. The only public space is the restaurant with a wonderful view of the Acropolis.

Once one passes through the turnstiles to enter the galleries, things change quickly for the better. The ramp to the first display floor is long and gradual, concluding in a stair. All along the ramp are cases with artifacts and good signage. It is a pleasant and well-designed space. The materials are smaller items, mostly from the slopes of the Acropolis and smaller sanctuaries (according to the museum's press kit - I remember no general description of the gallery space indicating that). At the top of the stair is the pediment of the Hekatompedon. The setting, at the top of the stair, is excellent for the pediment. And it leads to a wondrous first floor of displays.

The entire floor has only the walls of the stair-ramp central core and a number of those unfortunate columns to interrupt the space, and in that space - lighted with the daylight coming through the glass-curtain façade and some reflections from interior surfaces - are many of the most wonderful items from the Acropolis. They are on pedestals generally, not in cases or against walls; so they can be seen from all sides and examined from as close as one wishes to be; no glass to intervene between the eye and the object. The ambient light was one of the basic design concepts, and it is very well used here. It is more than adequate without being harsh.

Also on this first main floor are exhibits concerning the Propylaea, the Nike temple, and the Erechtheum. Much of the Erechtheum material is actually in a kind of loft over the ramp leading up from the ground floor. The caryatids are displayed there. The lighting is not ambient light there, but it is excellent lighting, good enough for careful examination of the pieces but not glaring. Here again the proximity afforded by the museum display system is startling and wonderful. The individual caryatids can be examined from as close as one can imagine.

There are models of the Acropolis on display here as well, models intended to show the layout of the entire Acropolis at various important times. One of those is, of course, 480 B.C.E., and it was disappointing to find the model showing a large older propylon of the scale of the Propylaea; it is shown as under construction in 480. While I understand that my own view of the entrance has not been accepted by all, I was surprised to find a restoration that stands on no physical evidence whatsoever - not a column or other remaining piece from a building of the scale of the later Propylaea has been found.

I regret being unable to say more about the displays of the materials from the Propylaea, Nike Temple, and Erechtheum, but I must confess to having given them too little attention. Like so many visitors, I was attracted to the final stage, the floor with the Parthenon materials, too strongly to spend more time with these buildings I feel I know already.

The top level and the Parthenon materials are accessed via an escalator rather than a ramp or steps. This yields more floor space in the core for display, and there is a good introductory video shown there. It seemed well done to me, although some of the animations were too fast for my taste. (Hoping to find the video online, I checked and found only an 8-minute video entitled "Reflections," directed by Athina Rachel Tsangari, which I watched. Alas, it was not the Parthenon video and was for me a vacuous and pointless product.)

The Parthenon floor is in so many ways the culmination of this building that I am loathe to launch into a discussion too abruptly. Not only is this intended to provide the visitor with all the wonders of the sculpture on the building (though some metopes have yet to be moved from the Parthenon), it has been prepared in such a way as to emphasize the missing Elgin marbles as if that would hasten their return. (The first minute and a half of this You Tube video "Bring Them Back" - in Greek with English subtitles - seems a far better approach to me, though the later portions of the video lapse into something quite different.)

The display consists of the surviving pieces from the metopes, the frieze panels, and the pedimental sculpture (absent the missing pieces now in London or still on the building - all represented by casts, with white used to emphasize the pieces in London) arranged around the core of the museum, the size of which, on this floor, is that of the cella of the Parthenon. (The orientation of the core has also been matched to that of the Parthenon on this floor.) The ceiling is lower here than on the lower floor, and, as a natural result, ambient lighting is insufficient. There is good artificial lighting, enough to allow everything to be well seen but not so much as to be bright and distracting. The metopes, the frieze panels, and the pedimental sculpture are all lighted well and carefully. All can be seen clearly, and all are at a height that makes it possible to see them well and examine them thoroughly.

The metopes and frieze panels are related to themselves and to one another as they were on the Parthenon - but as to plan only. That is, their heights relative to one another, not to mention the viewer, are not correct. The pedimental sculpture is displayed in front of the metopes and somewhat lower so that the pedimental pieces are not properly related to any of the others as to plan or elevation.

In addition, the building, when whole, would have included a ceiling over the passageway between the colonnade and the cella wall, on which the frieze was positioned. That ceiling would have prevented any direct sunlight from reaching the frieze; the only light would have been reflected light from the surfaces of the Parthenon or, further away, those of the Acropolis generally. As a result lighting in antiquity would have been very limited for the frieze panels.

The foregoing is to point out that, despite the careful size and orientation of the building core to match the Parthenon cella, the display is, for this viewer, unsatisfying. The internal relationships are not what they were when the building was whole. The lighting is very different from what it was on the Acropolis, both as to its overall intensity and as to the light reflecting onto the frieze. The viewpoints are completely different from those available to a visitor to the Acropolis at any time in its history because of the heights at which the objects have been set. Nothing about this display allows a naïve viewer to imagine the reality of the building in its glory on the Acropolis. Knowing that this is a personal opinion, I wish to be careful here. The display offers a level of access that is impossible if the individual pieces are as far from the viewer as they were on the building. It retains the internal relationships of each metope to each other metopes and of each frieze block to each other frieze block. It may therefore be a good compromise. But not to me. I can imagine other ways to display these pieces - more complicated and more expensive as a result, to be sure - that might provide the best of both worlds.1

Putting the parts together, the new museum is such an improvement that complaints such as those I've made here seem unimportant. On the other hand, it seems a shame to waste an opportunity to make something wonderful.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

Notes:

1. One thought as an example: a full-sized near-replica similar to what is in the museum today but with all sculpted parts in their proper locations relative to one another and the visitors, a ceiling over the frieze, lighting approximating the out-of-doors, and some form of gallery to permit close inspection of the various levels. Such a gallery could be movable so that one would have periods when close access is possible and other periods when - with the gallery pulled away - it is not and when viewers could see the whole ensemble as an ancient viewer might have, unencumbered by the gallery.

Similarly, there might be two lighting setups, one approximating the out-of-doors conditions and one softer, for close viewing. Return to text.

All articles in the CSA Newsletter are reviewed by the staff. All are published with no intention of future change(s) and are maintained at the CSA website. Changes (other than corrections of typos or similar errors) will rarely be made after publication. If any such change is made, it will be made so as to permit both the original text and the change to be determined.

Comments concerning articles are welcome, and comments, questions, concerns, and author responses will be published in separate commentary pages, as noted on the Newsletter home page.