| Vol. XXIII, No. 3 | January, 2011 |

Articles in Vol. XXIII, No. 3

Bridging the Communication Gap: Should academics go public with what they know?

Speaking beyond the walls of academe.

-- Peter A. Young

Project Publication on the Web — I

The first questions are easy to ask, harder to answer.

-- Andrea Vianello, Intute and Harrison Eiteljorg, II

Website Review: Petras Excavations

An archaeological project published on the web.

-- Andrea Vianello, Intute

Aegeanet

A short history of the long-running listserv.

-- John G. Younger

A Review: AutoCAD® for the MAC 2011

More like an upgrade than a new version.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

The Skies Are Clouding Up Even More

Keep your data where you can find them.

-- Harrison Eiteljorg, II

To comment on an article, please email

the editor using editor as the user-

name, csanet.org as the domain-name,

and the standard user@domain format.

Index of Web site and CD reviews from the Newsletter.

Limited subject index for Newsletter articles.

Direct links for articles concerning:

- the ADAP and digital archiving

- CAD modeling in archaeology and architectural history

- GIS in archaeology and architectural history

- the CSA archives

- electronic publishing

- use and design of databases

- the "CSA CAD Layer Naming Convention"

- Pompeii

- pottery profiles and capacity calculations

- The CSA Propylaea Project

- CSA/ADAP projects

- electronic media in the humanities

- Linux on the desktop

Bridging the Communication Gap: Should academics go public with what they know?

Peter A. Young

(See email contacts page for the author's email address.)

In a column for Archaeology magazine, Randall McGuire recalled a reception at SUNY, Binghamton, during which

the vice president blocked my advance to the hors d'oevres table and asked what I had done over the holiday break. I told him I had just returned from an excavation in Arizona. "What did you find?" he asked. I gulped hard and explained that the research design of the project was to test competing theories of social complexity in the Hohokam Sedentary Period, that proving one theory would help resolve debates about the nature of cultural change, and that it would take us several years to resolve the issue.

As I spoke, his eyes glazed over. I started to perspire, knowing that in all probability I was blowing my chance to impress a man who could say yea or nay to my bid for a permanent position at the university. Finally, he blinked, shook his head quickly, and asked if I had met the chair of the mathematics department. I said no, whereupon he introduced me by saying I had just returned from a dig, and before I could brace myself the mathematician asked, 'What did you find?'

Titled "The Dreaded Question" because McGuire at first didn't know how to answer it, the article went on to explain how he did try new avenues of approach. "Archaeologists," he wrote, "take the bits and pieces that they unearth and splice them together to tell a story, much like a director combines scenes to make a film. But, unlike a movie, the archaeological process has no end. There is always some detail or scene left out, so we are forever editing and changing our movies. I always fear that the people who ask, "What did you find?" will be disappointed with our brand of cinema. They expect a four-real epic — Charlton Heston parting the Red Sea — when in fact we are making home movies. The film is poor quality, the image grainy, the focus bad, the subject mundane." Eventually, McGuire learned to answer "the dreaded question" with a light anecdote, one for instance about a WWII live grenade that turned up at a site, to the consternation of local police. (It turned out to be a smoke bomb someone had brought home from the war as a souvenir.) "If the anecdote fails to generate interest in what I do," he concluded, "I revert to small talk. If it does spark some interest, I talk about the movie." McGuire's experience highlights a dilemma faced by legions of archaeologists — how to meaningfully communicate with the general public. Should they even try? The answer, of course, is "yes," lest, in the words of one of Archaeology's academic contributors, "we are left talking to only a steadily shrinking group of peers, while our fellow citizens embrace a vision of antiquity that consists of little more than noble fragments and colorful caricatures." Nonetheless, to many scholars the challenge is mind-boggling. How, they ask, do you write a magazine article or book that commands a lay reader's or even a fellow scholar's attention? How do you give a public lecture that doesn't put everyone to sleep? How do you curate a museum exhibition that excites and attracts multitudes of kids and their parents? How do you create an exciting, provocative website that appeals not only to fellow scholars, but to the general public as well? In sum, how do you hold the attention of readers, listeners, television viewers, website browsers, and fellow academics? Answer: By telling a story — your story — about what you did, why you did it, what you learned, and why anyone should care to know about it. It's a matter of changing your mind-set, to see your own work from the public's point of view, perhaps even learning or appreciating some new or unusual way of looking at what you have being doing year after year.

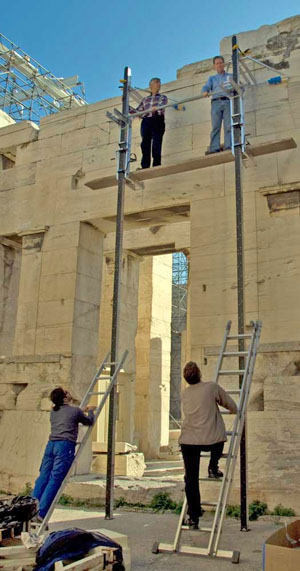

CSA director Nick Eiteljorg excavated and studied the older propylon, the defensive entranceway to the Athenian Acropolis that was later replaced by the magnificent gateway whose ruins we see today, the Propylaea. Ask him how he feels about engaging the public in discussions of the older entrance and he'll tell you this:

I found giving public lectures about my work extremely helpful in making me see things more clearly. Explaining what I knew about the old entrance to an audience of non-professionals made me work much harder to see the kinds of connections and relationships that matter in a larger, more general way. For instance, it was when speaking to the Archaeological Institute of America's Society in Rochester, NY, that I first realized how important the ancient Mycenaean wall was to fifth-century Athenians, because it had been part of the old, defensive entrance structure. I can still remember walking away from the lectern and microphone to the end of the stage and saying, in a kind of actor's stage whisper that surprised me, 'It's the wall. It's about the wall.' This was not a specialist's fact, it was a critical way to understand the Athenians' understanding of the old entrance building, which was part of the Acropolis' defenses. That was something I might never have seen had I not been trying to make the results of my project sensible to a general audience. It was also something that — and I say this in part on the basis of reaction to the talk — helped to get the members of the audience to see my work as having value and relevance beyond the technical details of the old entrance building. It elevated the talk to a discussion, at least in part, of the way one might expect an ancient and venerated space to evolve over time.

When I became editor in chief of Archaeology 24 years ago, there was no consensus on such matters. "Scholars should communicate with scholars," I was informed by one classics professor, who felt writing for the magazine was quite beneath him, in fact was a form of sellout. "I would frown upon it," he said. Another told me, "I'm an archaeologist, not a storyteller." He was quite disinterested in sharing his work with the general public, preferring to communicate only with fellow scholars, sometimes in jargon mysterious to all but themselves. With 30 years of magazine experience but little familiarity with archaeology at the time, I was in no position to comprehend many of the papers read at annual conferences, dealing with profound subjects like processual paradigms, hypothetico-deductive models, technotypologic patterns, and so on.

In those early days, the magazine had what we called a "manuscript doctor," a professor of English literature and fastidious student of the English language. It was Dick Wertime's job was to pay a personal visit, if possible, to academics whose work was of interest to the editors of the magazine and whose writing, usually in need of considerable enhancement, could be edited. They were told the process would be taxing but fair and that they would have final approval of the "doctored" text before it was published. They rarely, if ever, balked.

And then I met the great Mayanist Linda Schele, a consummate raconteur, passionate about what she did, with stories to tell that would make your head spin. In a 1991 interview, she noted that "the job I seem to have now is to provide the public voice — to give people access to the things scholars learn from people who study the modern Maya, and the approaches of many disciplines, and say to the public, 'Listen folks, let me tell you a story about a great king.'" Here was a born storyteller and a boon to an editor like myself, groping for new and interesting material in a rather strange land.

Linda was the first of many academics eager to tell their stories in the pages of our magazine. Jerry Milanich of the Florida Museum of Natural History was forever finding new Spanish mission sites in the southeast and his discoveries were rapidly rewriting the state's colonial history. "Hey Peter," he would shout, phoning from a newly discovered site. "De Soto actually came through here. And I've got artifacts to prove it." His excitement was palpable. He later confided: "If scholars rarely share their personal stories, it's probably because they aren't invited to. In fact, we're eager to convey the thrill of what we do. And why not? It's our emotional involvement with the past that drives archaeological discovery."

Equally passionate about what he does is Jim Delgado, former president of the Institute of Nautical Archaeology at Texas A & M and today the Director of the Maritime Heritage Program for the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). A member of the magazine's editorial advisory board, he would often regale us with stories that conveyed a profound love affair with underwater archaeology:

"I have seen history exactly where it happened. And at times I've been the first person to go into a place and to be the explorer who brings that story back. That's exciting! It's fun! It rocks! It happens! And it's not just a whatever thing because you know in your heart and you can see it, you can feel it, and almost taste it." The excitement for archaeology coming from academics themselves helped us win a Special Achievement Award from the Society of Professional Archaeologists in 1996. The award noted that the magazine had "correctly perceived that the excitement and importance of archaeology for the most part had lain hidden from the public in rather deadly academic prose. Rather than turn to professional writers as a remedy, the magazine had held to its belief that archaeologists themselves could best communicate the value of their own research and the significance of results produced."

In 1998, the year the magazine celebrated its 50th birthday, a commemorative issue was produced. In it, Kathleen Deagan, Richard Hodges, and Neil Silberman all wrote — from their deep scholarly interests and knowledge — in ways that spoke to magazine subscribers as well as fellow scholars. Deagan, of the Florida Museum of Natural History, took us on a journey through modern history, noting how archaeology had preempted the written record with discoveries that illuminated the actual rather than the imagined past—that slavery was common in the north, for example. Hodges, now director of the University of Pennsylvania Museum, examined the Not-So-Dark Ages, a world the author, as a child, had peopled with barbarians and troglodytes whom he later discovered to be "the merchant adventurers and skilled artisans who laid the foundations for modern Europe." And biblical scholar Silberman addressed the considerable advances in biblical archaeology, particularly a new theory that the earliest Israelites were not a phantom band of conquering desert nomads but people from within Canaan adjusting to the collapse of Late Bronze Age city-states. In each case, the scholar became story-teller, presenting readers with surprising tales of discoveries, all three informative, newsworthy, and entertaining.

Meanwhile, competition from a new publication, Discovering Archaeology, launched in 1999, served as incentive to raise the fees of both freelance writers and photographers. By this time, Milanich had become a contributing editor and the prospect of getting paid more for his efforts was, naturally, attractive. But there was another reason: audience. "For a professional journal you write an article about fish-eating practices two and a half millennia ago, including many citations of previous research on coastal archaeology. The journal editor sends the article to four reviewers who are all experts on the subject. One doesn't like it because I haven't cited his work."

Over the next year you revise and resubmit the article twice before it is finally accepted for publication. The copy editor then goes to work, cutting all the citations you added over the past year, having deemed them irrelevant. Six months to a year later, the article appears in the Journal of Ancient Indian Ichthyologic Ingestion that is sent to 900 subscribers, fourteen of whom actually read your article (and two are relatives who say it's boring).

With Archaeology, your article needs to be revised and crafted in a matter of days, not months. Revisions entail handling all sorts of queries and suggestions from the editors who anticipate what the magazine's readers will want to know. The article, intended to educate and entertain, not get you tenure, is electronically zipped off to the printer. Less than a month later, 230,000 subscribers read your article, more people than have read all the academic books and articles I've ever authored added together. That's why I'll keep writing for the magazine.

Today, more and more archaeologists are creating websites that seek to educate the public as well as interested fellow academics, in language virtually everyone can understand. One need only click on the web pages of the Institute of Nautical Archaeology (inadiscover.com) or the award winning Texas Beyond History (www.texasbeyondhistory.net) to experience extraordinary, well-designed sites, web books in fact, bearing a surprising wealth of clearly written, easily accessible information.

"All archaeology is public archaeology, in this country at least, and public archaeology should be a part of every project," says Milanich.

Engaging the public has also become an important focus of the Society for American Archaeology (SAA), which has launched a set of web pages (www.saa.org/public) linked to the SAA home page, rich with resources to meet the needs of both the public and the SAA's working archaeologists. A major point of contact between the discipline's largest professional organization and both friends — and foes — of archaeology, its resources include, among other things, information on archaeological law and ethics, heritage tourism, and educational opportunities, and a list of archaeological web sites both at home and abroad, evaluated by the SAA for their "public friendliness."

Web sites, like many scholarly publications, may not speak to the general public, and some scholars have suggested it would be in their interest — and the public's — to do so. For Eiteljorg,

the issue of addressing the public came up in the context of a discussion with a colleague about what a project web site ought to be. Should its audience be broad or narrow? Be only scholars or a wider group? I had already put the CSA Propylaea Project results on the web — in a firmly non-general-audience way. That is, what I put up was more of a data dump than any kind of public resource. The site had CAD models and data tables that users could download to examine at their own desks. This is our archive. But there is no "Here it is, Mr. Non-Scholar" point on our site, and there is certainly no attempt at a coherent start-to-finish story for the non-specialist. There ought to be some way for the non-specialist to get into this information.

Reviewing the web site of the Pylos Regional Archaeological Project (PRAP) in the CSA Newsletter, Kevin Glowacki, while praising PRAP for making available the results of its archaeological fieldwork in a timely and accessible manner, points out that the site "could also feature more didactic and explanatory sections for amateurs or students, including an expanded introductory essay, written for a general 'lay' audience, which summarizes the project's goals, methods, and results as well as outlining the history of archaeological research and interest in the area." (See csanet.org/newsletter/feb96/nl029605.html for the review.)

Were the creators of the Pylos Project website asked to describe what they had learned from their expedition in Western Greece, they may well have been, like Randall McGuiire, hard pressed to provide a particularly reader-friendly answer, if the wording on their home page serves as any guide. Their project, they are careful to explain, "is a multidisciplinary, diachronic archaeological expedition to investigate the history of prehistoric and historic settlement and land use in western Messenia in Greece." Would anyone but another archaeologist know what they were talking about? Did it matter? . . .

-- Peter A. Young, editor in chief of Archaeology magazine until his retirement in July, 2010

All articles in the CSA Newsletter are reviewed by the staff. All are published with no intention of future change(s) and are maintained at the CSA website. Changes (other than corrections of typos or similar errors) will rarely be made after publication. If any such change is made, it will be made so as to permit both the original text and the change to be determined.

Comments concerning articles are welcome, and comments, questions, concerns, and author responses will be published in separate commentary pages, as noted on the Newsletter home page.